Home>Two Years Already? Peace Between Eritrea and Ethiopia

26.08.2020

Two Years Already? Peace Between Eritrea and Ethiopia

Nothing expresses more clearly the critical dimension of peace between the two countries of the Horn of Africa than the comparison of tweets published in English and Tigrinya on 9 July 2020 by Minister of Information Yemane Gebre Meskel in Asmara, on the occasion of the anniversary of the peace treaty signed between Eritrea and Ethiopia.(1) For English-speaking readers, the Eritrean regime welcomed the peace agreement and expressed its hope for intensified cooperation with Addis Ababa. For those who read Tigrinya, i.e. a large part of the population of Eritrea and the neighbouring Ethiopian Tigray, everything remains to be done: the peace agreement is a huge disappointment and foreign (i.e. Ethiopian) forces are still present on the national territory.

To understand this quite original stance of the Eritrean government and the lack of reaction of Addis-Ababa, one must go back to the conditions under which peace was concluded and to the Ethiopian political dynamics that have developed since the coming to power in April 2018 of a new Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in December 2019 for having put an end to a “20-year” war between the two countries.

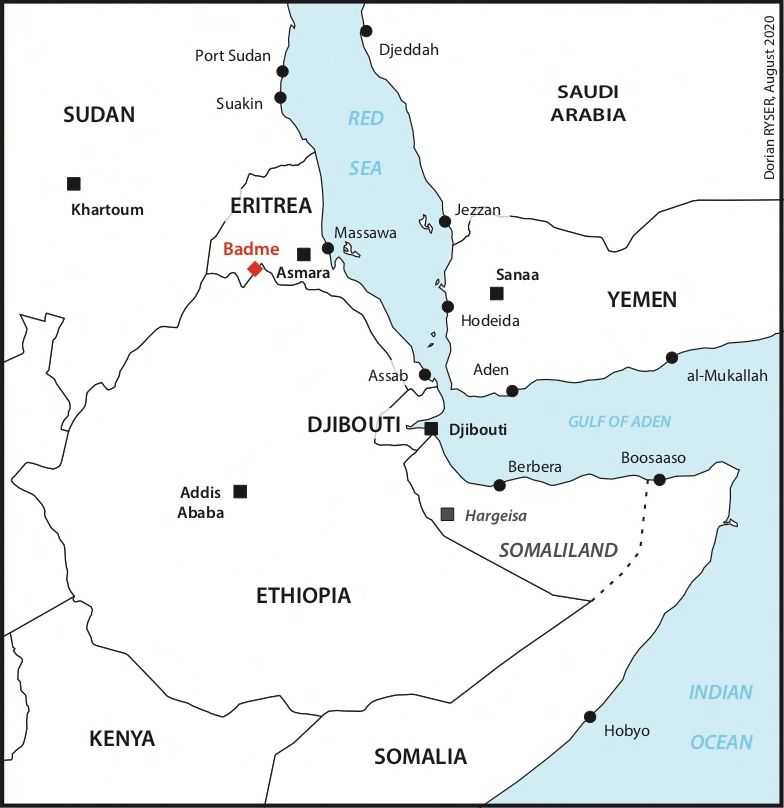

Begun in the spring of 1998, this inter-state conflict caused nearly 100,000 deaths. A ceasefire in June 2000 was formalised by a peace treaty signed in Algiers in December 2000.(2) Although the reasons for this conflagration were complex, the conflict was described as a border war, and the status of the village of Badme, located at the border and claimed by both countries, was used as a symbol of what was at stake.

Contrary to the commitments made by the international community and the two protagonists in the conflict in December 2000, the decision of an International Commission ruling on the border between the two countries was not enforced by Addis Ababa in 2002. No pressure was then exerted on Ethiopia by powerful donors (notably the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom), because the country was recognised by Western countries as the hegemon of the Horn of Africa and a strategic partner in the fight against terrorism after 11 September 2001.

As in 1952 and 1961,(3) irrespective of all the reservations one might have had about its political regime, Eritrea saw its rights violated and its behaviour as a regional spoiler vilified without anyone in any way questioning the external responsibilities involved in such behaviour. A UN peacekeeping force that was supposed to avoid any escalation in the disputed territories was mishandled and had to pack up in December 2008 at a time when Asmara was accused of supporting the Ethiopian armed opposition and the Somali jihadist group, the Young Fighters’ Movement (Xarakada Mujaahidiinta Alshabaab), which provoked UN sanctions in 2009.(4)

However, even if the front lines in this conflict appeared to be frozen, American diplomacy was discreetly working toward normalisation beginning in 2017. This new state of affairs was less a result of Washington’s aggiornamento than of friendly pressure exerted by the Saudi and Emirati allies who had gained a foothold in Eritrea and Ethiopia and intended to develop an alliance of the countries bordering the Red Sea—which finally came into being in January 2020.(5) This period was also marked by the intensification of often violent social struggles in Ethiopia, which highlighted the exhaustion of a regime established in 1991 by Meles Zenawi, who himself died in 2012 of an aggressive cancer.(6) The old world was collapsing and peace between the two countries could belong to the new one.

In June 2018, when Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, appointed only two months earlier, acknowledged the decision of the International Boundary Commission and in particular the fact that Badme was part of Eritrean territory, there was no real surprise as the Prime Minister had taken strong initiatives to dismantle a regime that had long been pampered by the West despite its massive human rights violations. One of the reasons for the acquiescence of the Ethiopian public opinion was the fact that this peace with Eritrea was mechanically a war machine against the Tigray, associated with the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) that Meles Zenawi had led with an iron fist and that had been the backbone of the regime since 1991, especially its military and security apparatus. Abiy Ahmed played a similar card when he replaced the Ogaden administration (still called Region 5 or Somali Region). The latter had been the main ally of the TPLF and had helped neutralising the political representations of the two main components of the Ethiopian population, Amhara and Oromo (to which Abiy Ahmed belongs).

An Opportunity that Could Not be Denied

For Issayas Afeworki, Eritrean President since 1991, this opportunity could not be denied. For the first time since Eritrea’s independence, the leadership of Ethiopia was in the hands of a man who was not an ally of the TPLF and whose relationship with Meles Zenawi had been difficult; nor was he an Abyssinian (i.e. Amhara) and he did not represent the imperial project that built modern Ethiopia. Moreover, some of the Ethiopian opponents who had taken refuge in Asmara were advocating a reconciliation that would enable Eritrea to influence the political course in Addis Ababa, as Issayas Afeworki had always aspired to do.

For the Eritrean regime, the war was first of all a confrontation with the TPLF with which it had maintained difficult relations in the 1970s and 1980s before an ad hoc alliance in 1989 for the overthrow of Mengistu Haile Mariam.(7) This reversal claimed by the Ethiopian Prime Minister was a victory on several counts. On the one hand, it gave legitimacy to the domestic policy of the Eritrean regime, the militarisation of its youth in particular, by arguing that the war had been a just cause and that the sacrifices demanded year after year since 2000 had been rewarded. Such an argument undermined an entire section of the opposition which had been built up through a criticism of the strategy followed throughout the war. On the other hand, it emphasised the bad faith diplomacy of Westerners and their blind choices since the TPLF appeared to be the main loser and scapegoat for all the mistakes made since 1991 and 2000.

This common hostility to the TPLF helped cementing an alliance between the Eritrean President and the Ethiopian Prime Minister. The ceremonial aspects of this announced peace then held an important place in the communication of the two countries toward the world outside the region, until the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the young Ethiopian Prime Minister. This reconciliation also reassured possible international investors despite the competition between Gulf countries and a tightening of security in the Red Sea.

What is peace beyond the statements of these two leaders and the applause of the Western diplomatic community and its allies in the region? It was one thing for Ahmed Abiy to marginalise the TPLF. It was another thing entirely to dispossess Tigray (and thus Ethiopia) of part of its territory, which could provoke (without even raising here the issue of the status of the populations). In fact, the border between the two countries has been closed for a year and only opened intermittently and in a very localised manner until the spring of 2019. Only a daily flight between the two capitals allows us to state that the links remain, provided of course that one is able to pay for a ticket and get a seat on this plane. Peace, certainly, but peace of and for the elites. The people living in the areas concerned are the first to be forgotten in such a celebrated moment.

In the first weeks of 2018 summer, the situation was indeed quite different. The population on both sides of the border celebrated its reopening, families were reuniting after almost two decades of separation, and cross-border trade was exceptionally vibrant: while Eritreans were selling electronic products acquired in the Gulf, the Tigrayan populations were selling agricultural goods and construction material.(8) But the situation deteriorated from September 2018 onwards.

Flows were not limited to goods but also involved people. The number of Eritreans (especially women and children) seeking asylum in Ethiopia increased exponentially (about 30,000 per month). As a result, the Eritrean government decided to close the border. Officially, this decision aimed to regulate cross-border trade and to define new procedures for the use of the two national currencies, Birr and Nakfa (an issue which had been a further reason for the 1998 confrontation). The population, who should have been best able to carry and consolidate peace, was excluded.

What has Changed?

But there is something even more worrying at a political level. While the status of Badme is no longer contested, no significant change has been noticed in this area or elsewhere on the border. The demarcation that was controversial for 18 years and accepted since 2018 remains as virtual today as it was when the International Boundary Commission was dissolved in 2007. This implies that Ethiopian soldiers still occupy Badme and that the heavy weapons remain there. It also means that the people living in the disputed areas have no idea of their future status: Eritrea and Ethiopia will each lose more or less territory if the demarcation of the border follows the advice of the International Boundary Commission.

Although the visits that the two leaders have been making to each other since July 2018 continue and the communiqués that conclude them still celebrate the deepening of cooperation for the development of the two countries, no text signed by the two governments can convince normal people that what brings their leadership together concerns the future of their populations beyond a common hostility towards the TPLF. Even the port of Assab, which had been Ethiopia’s main access to the sea from 1991 to the end of 1997, remains inaccessible to Ethiopian companies, despite some announcements that it would be opened. The UAE is carrying out modernisation work there for its own interests—including the conduct of war in Yemen—but no text accessible to the Ethiopian public specifies the conditions for using this infrastructure. In the 1990s, despite the promises made and diplomatic speeches delivered, disputes between Ethiopian operators and Eritrean managers of the port of Assab had multiplied and had considerably deteriorated relations between the two countries before the border incident of April 1998.

While it is difficult to identify markers of this peace in the relations between the two countries, at the internal Eritrean level, the hopes raised by the announcement of peace have also been dashed. Indeed, the Eritrean regime soon found itself in a dilemma: while it could put an end to a highly unpopular forced conscription, or at least reduce its duration and scope, such a decision implied offering jobs to demobilised conscripts and meeting some of their demands in terms of lifestyle perhaps more than in political terms. Moving in such a direction meant a risk(9) that the Eritrean leadership was unwilling to take. Some within the security apparatus were reluctant to support a liberal change because they were getting a real rent from the existence of such a workforce that could be enticed to work at will or was ready pay dearly to cross the border and escape Eritrea. Suddenly, it would have been necessary to accept a lesser control on the market, a competition with new economic operators not linked to the figures of the regime and the single party. This was not impossible, but it did not interest a regime that knows that it can benefit from substantial international aid to curb exile seekers and a mining potential (like Ethiopia) that would generate small development enclaves more than an overall improvement of the national economy.

The Eritrean diaspora has not necessarily played a positive role, first of all because of its numerous divisions which the unanimous condemnations of the Eritrean President have difficulty concealing. Making Issayas Afeworki responsible for all the misfortunes of Eritrea hardly offers any realistic alternative strategy to his rule, or on the economic development of a country which requires the financial mobilisation of Eritreans abroad, today and tomorrow. Nor does it offer a very convincing view of the Ethiopian political scene, first of all in Tigray, where relations between the TPLF and the population have evolved because of the dangers that the stigmatisation of Tigrayans (and no longer only of the TPLF) in Ethiopia triggers today.(10)

As has occurred in the case for Barack Obama’s nomination for the Peace Prize, the Nobel Committee is criticised for having been too quick to offer Abiy Ahmed a status that is going to vanish in an increasingly authoritarian management of political upheavals on the Ethiopian scene.(11) Peace with Eritrea has not really triggered new regional dynamics, even if it has appeased the allies in the Gulf, offered space to Eritrea, and put in new terms the relations of Addis Ababa with Djibouti, Hargeysa, and Mogadishu. Issues such as the Great Renaissance Dam, the pacification of the political arena in Southern Sudan, and the deterioration of relations between the government in Mogadishu and a good part of the Somali federal states are complex and it seems that Abiy Ahmed has hardly taken the time to measure the depth of certain problems. His attempts at mediation are often based on a history that is more complicated than he wants to admit and over which he has little control as he remains superficial.

A New Authoritarianism?

While no one can blame him for these semi-failures at the regional level, another impression dominates the analysts’ assessment of Ethiopia’s domestic political dynamics. What appeared at first to be flaws linked to lack of experience is seen today as constituting a new authoritarianism whose violence is no less than that of the one it replaced in 2018.(12)

From the outset, his willingness to play a disproportionate role, side lining institutions and scorning the maturing of opinions through collective debate, appeared to be an important weakness that was not counterbalanced by his evangelical discourse on peace and love, which no doubt earned him additional consideration from the American ambassador in Addis Ababa (a fellow evangelical indeed), but increased scepticism among the Ethiopian population, who are too familiar with violent repression and mass arrests to give credence to these speeches.

The reality is much darker than most American and European chancelleries want to admit. After the murder of a popular singer, Abiy Ahmed appeared dressed in military fatigues on national television; the internet was cut off for over a week and media outlets were banned, while politicians who were among his top allies were fired or even imprisoned. The authoritarian tendencies of the period 2001-2018 when the TPLF led Ethiopia had been rightly denounced by Abiy Ahmed who nowadays seems to have been inspired by them without any particular emotion, sure of the support of Washington, London, and Paris (as well as Beijing) and the follow-up of international organisations such as the IMF or the European Union. Peace, genuine peace, seems even more difficult to achieve today than it was two years ago.

Notes

- 1.See https://eritreahub.org/charlie-speaks-with-forked-tongue for the various references (last accessed on 11 July 2020).

- 2.For an excellent synthesis, see Richard Reid, Elite Bargains and Political Deals Project: Ethiopia-Eritrea Case Study, Stabilisation Unit, February 2018. Refer also to the work by Tekaste Negash and Kjetil Tronvoll, Brothers at War: Making Sense of the Eritrean-Ethiopian War, Oxford, James Currey; Athens, Ohio University Press, 2000.

- 3.Respectively, date of the federation of Eritrea with Ethiopia (agreement guaranteed by the United Nations but never respected from the very first day) and date of the unanimous vote at the Eritrean Parliament to “reintegrate” Eritrea into Ethiopia (a vote made easier by the presence of Ethiopian tanks surrounding the Parliament in Asmara).

- 4.Resolution 1907 of 9 December 2008. The sanctions were lifted in November 2018. Even if the support to the Ethiopian armed opposition movement was confirmed, questions remained regarding long-lasting support to Somalian jihadi fighters. In spite of Ethiopian pressure or attempts to manipulate them, UN experts had to accept that such help—had it ever existed—was over as of the early 2000s

- 5. https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20200108-new-red-sea-alliance-formed-saudi-arabia-notable-exclusions. This alliance, with various goals, aimed as much to contain Qatari ambitions in the Horn of Africa as to control through coercion the Iranian presence in the Red Sea, in order to counterbalance the military manoeuvres of the Guardians of the Revolution in the (Persian) Gulf. The summer of 2019 offers a great illustration of what was at stake.

- 6.Jeanne Aisserge and Jean-Nicolas Bach, , Observatoire de l’Afrique de l’Est, November 2018.

- 7.John Young, “The Tigray and Eritrean Peoples’ Liberation Fronts: A History of Tensions and Pragmatism”, Journal of Modern African Studies, vol. 34, n°1, 1996, pp. 105-120.

- 8.Tanja Müller, , Observatoire de l’Afrique de l’Est, September 2019. For a point of view by scholars from Tigray, see Mitiku Gabrehiwot Tesfaye and Mahlet Alemu Gebrehiwot, “A ‘Party’ at the Border: An Anthropological Take on the Ethiopian-Eritrean Peace Deal of 2018”, Cogent Arts & Humanity, vol. 7, n°1, 2020

- 9.As President Issayas declared during his speech on Independence day in May 2019, “this is a new situation and we first need to know all the implications”.

- 10.Ermias Amare, “TPLF’s Last-Man Standing”, Ethiopia Insight, 30 November 2019.

- 11.Jeanne Aisserge, , Observatoire de l’Afrique de l’Est, August 2019.

- 12.For a detailed analysis that ought to be better taken into consideration by international diplomacy, from Washington to Beijing, London, Paris, and Brussels, see René Lefort, “Preaching Unity but Flying Solo, Abiy’s Ambition May Stall Ethiopia’s Transition”, Ethiopia Insight, 25 February 2020

(credits: Dorian Ryser, CERI)

Follow us

Contact us

Media Contact

Coralie Meyer

Phone : +33 (0)1 58 71 70 85

coralie.meyer@sciencespo.fr

Corinne Deloy

Phone : +33 (0)1 58 71 70 68

corinne.deloy@sciencespo.fr