Home>Digital Utopianism: Where Do We Stand 10 Years Later?

21.06.2023

Digital Utopianism: Where Do We Stand 10 Years Later?

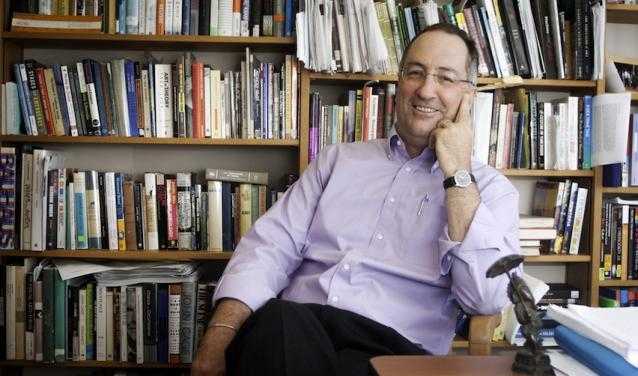

To mark the tenth anniversary of the publication in French of his book From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network and the Rise of Digital Utopianism, Fred Turner gave a conference at Sciences Po on Friday 16 June, to look back on the digital utopia that surrounded the advent of the Internet. He shared some of his thoughts with us.

How have the utopian dreams of the 1990s evolved? Have some of them become a reality?

In the 1990s, almost everyone agreed: the internet would give individuals a new voice in public life and make it possible to create a society built around the expression of individual desires. In this ideal society, governments would melt away. Social order would simply emerge from the constant interaction of technology-enabled individuals.

Today we know better. We do indeed inhabit a world in which individual voices and desires have been unleashed at global scale. And many of those voices, especially but not exclusively on the right, hope to tear down the institutions of government. We are beginning to see that such a world is hardly the easy-going utopia promised by the Californian ideologues of the 1990s.

We’ve learned, first, that the broadcasting of relatively unmediated individual voices at scale doesn’t produce social order; it produces cacophony. Second, we’ve discovered that some voices are louder than others and to pretend we all access the internet on equal terms is to obscure the kinds of inequality that marble our society. Third, we’ve finally begun to recognise that the internet has never been simply a matter of individuals and their computers. It has always included large corporations, state actors, and economic and political incentives more powerful than anything an individual voice can shout down.

Today, we can see that the individual-centered utopia promised in the 1990s has helped spawned corporate concentration at a global level, political polarisation, and a deep personalisation of public debate. The only way that I can think of to repair the damage is to invoke the power of representative institutions – i.e., democratic governments – to try to rein in the consequences of a social and technical revolution that has turned out quite differently than many thought it would.

Do you believe that the new (and not so new) comers – such as social media, Artificial Intelligence including ChatGPT, OpenSource, NFTs – are creating a new utopia? Is it realistic and useful to try and regulate them?

No, they’re not, and yes, it is. Regulation is both realistic and essential.

But let’s start by dropping the idea of utopia. Utopias tend to be totalising systems – they promise to solve all problems at once using some semi-magical set of tools. In our time, the magical tools are digital technologies. But they’re not magical at all – they are the product of corporate and state enterprise and in the West, they are largely developed and deployed to serve the interests of commercial firms and their owners. Mark Zuckerberg may market Facebook as a tool to improve interpersonal relationships, but as a generation of scholarship has taught us, it has also been a profit-driven engine of political polarisation around the world. The fantasy that being able to talk to one another on screen would somehow create a warmer, more intimate society is and always has been just that: a fantasy.

The question is: How can we help the technologies we’ve built serve the public interest?

We can start by disbelieving the claims that accompany each new technology, the claims that this device or system – social media, AI, cryptocurrency – will change the world. This is marketing, not reality. When we burn away the marketing cloud, we can start to see the work of these technologies not as new and magical, but often, as new iterations of an old industrial processes.

Social media firms, for instance, make their money mining our social interactions, transforming them into data, and reselling that data. Like oil exploration or coal mining, their work has had terrible environmental effects. Facebook has literally helped pollute America’s political culture, not to mention the politics of other nations.

Across the twentieth century, governments found a way to identify and manage the social consequences of drilling for oil and coal, albeit only after great struggle. We need to do the same thing now for social media, as well as AI and cryptocurrency. The alternative is a political version of global warming, a slow pernicious rise in the temperature of public debate and a melting away of civility.

How can future generations, among which students from Sciences Po, help the utopia thrive and change the world in a positive manner?

Well, I’m afraid that many years of studying promises of technological utopia tells me that utopias are not what we should fight for. We need to fight for things that are much more mundane: the survival of representative government; the reduction of economic inequality; a halt to carbon pollution and climate change. Technology will play a role in all of these efforts and Sciences Po students will have the training and institutional access to figure how best to use it.

Some social problems are amenable to technological solutions; many are not. Sciences Po students will have training to let them see which is which, and to improve the world accordingly.

MORE INFORMATION:

- Science Po's médialab

- The article "Strong links between social inequalities and political activism" by Jen Schradie in Cogito, Sciences Po's Research Magazine.