What the European far rights share on social networks

6 May 2019

Creative Commons and Open Source licenses – Do digital freedoms conflict with property rights?

6 May 2019by Jen Schradie,

Assistant Professor, Researcher at the Center for Studies in Social Change

The promises of digital democracy

We had such high hopes for it. That disruptive digital darling of Silicon Valley, Cairo, Madrid, London and now Paris. We really believed it would solve so many problems of the world. When the internet was in its infancy, we were optimistic for its future to help make the world a better place. We nurtured it and gave it free reign. When it started to grow and went through its rebellious adolescent phase, we supported its new-found connections with social networks, and we had faith in its revolutionary democratic power to enable ordinary citizens to have a voice. It’s now an adult, though, and it should know better. But it doesn’t. The internet was supposed to do many things economically, socially, and yes, politically. But this belief in giving technology some type of inherent lifeforce and super-power capabilities has always ignored the broader societal structures that shape what it can and cannot do. But as many now turn toward the internet’s dark side of bots or fake news, we cannot just look to individual villains, such as Zuckerberg, Putin or Trump. Because if we do, we continue down the path of thinking that getting rid of them will re-create a utopian digital space. Instead, its democratic potential has never been met because of how the internet further amplifies dominant voices and marginalizes people who already had little power.

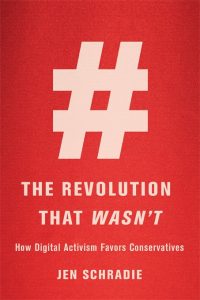

The Might of the Right

In my new book, The Revolution That Wasn’t: How Digital Activism Favors Conservatives, (Harvard University Press 2019 – translated in French, L’illusion de la démocratie numérique. Internet est-il de droite ? , Quanto, March 2022 ), I show that pluralistic ideals are shattered not by an army of trolls but by a system of inequality. Rather than everyday people connecting with each other politically in a new egalitarian and horizontal digital network, the digital tendency is for elite, hierarchical and conservative groups to dominate online activism spaces.

Much of the digital activism research has focused on successful, visible political movements, whether recent the Arab Spring or the Indignados. The problem is that this approach has skewed our findings toward movements of people who are already digitally active and away from a broader view of how online activism happens on a day-to-day level.

A broader view: the ordinary versus the extraordinary

Wanting to go beyond high-profile movements that might bias my findings, I chose a local political issue that would attract different types of groups that would vary based on social class, political ideology, and organizational structure. The issue was collective bargaining rights for public employees in the state of North Carolina in the U.S. All in all, this issue attracted 34 different groups that ranged from young student activists and other anarchist-minded groups to older right-wing group, many of which were bureaucratic in their structures. Rather than old school traditionalists who shun technology out of principal, labor union activists in the rural south operate more like social movements because of their uphill battle – often working with youth, civil rights and other activist groups.

By measuring digital engagement levels by creating a digital activist score based on Twitter, Facebook and Website metrics, I could evaluate the extent of online digital activity of not only the groups but also activists around the issue. Much fanfare has been made about digital activism being tied to left-leaning, horizontally-minded, common people. But I found that the highest levels of digital participation with conservative, hierarchical and resourced institutions. Simply, results showed persistent digital activism inequality.

Contextualizing the digital data

To better understand online activism, we have to devote offline time to contextualize it: I therefore also spent countless hours in 12 cities and towns across the state interviewing everyone from far-right Preppers to labor organizers. And I observed meetings, protests, and their everyday political organizing practices, including their digital use. But I not only analyzed the online digital footprint, I also spent countless hours in 12 cities and towns across the state interviewing everyone from far-right Preppers to labor organizers. And I observed meetings, protests, and their everyday political organizing practices, including their digital use. To better understand online activism, we have to devote offline time to contextualize it.

-

Inequalities, Ideologies and Institutions

The widest gap derived from social class differences. Middle/upper class groups not only used the Internet more than their working-class counterparts, but they generated much higher levels of online participation, such as 50 times more Facebook comments, on average per day. Three mechanisms drove this social class digital activist inequality. First, organizational resources, in the forms of digital gadgets and online expertise, were scarce among working-class groups but proliferated among middle/upper class ones. Next, individual constraints diminished online activism. Marginalized activists were much less likely to have internet access, digital skills, empowered confidence, and simply the time to use digital tools. Finally, contextual factors limited working-class activists, many of whom were African-American, as they feared repression with job loss or faced threats from publicly engaging online. The networked individualism of the internet did not serve the collective needs class power constraints

The next explanation for the digital activism gap also ran counter to networked expectations. Rather than horizontal groups dominating the digital activism space, it was hierarchical ones. Groups with more of this infrastructure often had staff or an army of volunteers who had the expertise to not only develop but also maintain digital engagement. A digital activist was more likely to be an elderly Tea Party member than a young student activist. But even more influential were bureaucratic organizations that had media staff who had honed their skills in the dark arts of digital memes and manipulation.

Finally, political ideology drove digital differences, but it wasn’t egalitarian-loving groups on the left but freedom-focused organizations on the right that embraced the internet’s ability to counteract what they considered mis-information. Yes, these cries of fake news drove conservatives to spread what they called “The Truth” on social media. Left-leaning activists, though, often considered the internet one of many tools to organize a set of diverse voices, not pump out a simple stream of freedom messages that the right did.

-

A vicious circle

But these three factors – inequality, institutions and ideology – did not work in isolation. They amplified each other to create this wide chasm of the digital activism haves and the have-nots. Working-class groups on the left, for instance, were simply not on Twitter, so when hashtag searches dominate journalist or researcher tool kits on tracking digital activist trends, some voices will be left out of this equation. But conservative activists are grassroots in their own right but also have a vast well-funded right-wing media eco-system to feed their digital spaces.

What about the “rest of the world”?

But wait, maybe this digital activism gap is just an outlier of one issue in one state in one country. How can we apply these findings to other countries and contexts? In many ways, that is the point. It is essential not to generalize any pocket of digital activism. We must dig deep to find where other inequalities and structural differences lie. And marginalization is prevalent in every country, whether France or anywhere else in the world. As we search for #GiletsJaunes or #MeToo, what types of voices dominate and which ones are drowned out.

Digital democracy is a mere fantasy when structural differences and inequalities not only persist online but may be exacerbated by the technological dominance of conservative elites.

Assistant Professor and researcher at the Center for Studies in Social Change, Jen Schradie focuses her works on the digital divide, digital activism, and digital labor. Schradie’s research is at the intersection of stratification and inequality, communication media and technology, labor and social movements, as well as political sociology and public policy. Incorporating qualitative and quantitative methods with both online and offline data, Schradie contextualizes disparities and variation of participation in digital society. Her current comparative project focuses on gender and class differences in the start-up economy in France and the U.S., and another examines online hate speech against Muslims. More about Jen

Jen Schradie – The Revolution That Wasn’t: How Digital Activism Favors Conservatives, Harvard Press University, May 2019

Jen Schradie – The digital activism gap: How class and costs shape online collective action, in Social Problems; February 2018

Jen Schradie – The digital production gap: The digital divide and Web 2.0 collide, in Poetics, April 2011