Home>David Camroux: “The Myanmar military junta has fallen for its own propaganda”

26.03.2021

David Camroux: “The Myanmar military junta has fallen for its own propaganda”

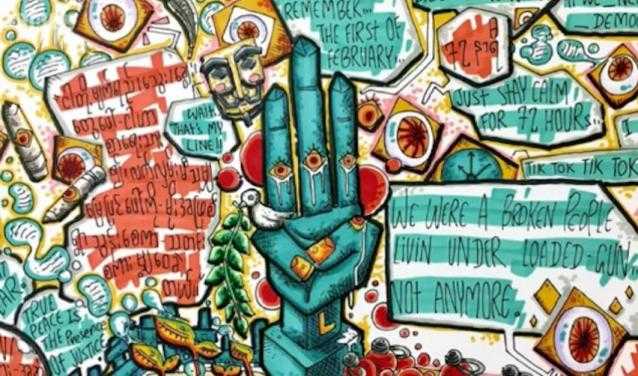

On 1 February 2021, just minutes before the swearing-in of newly elected members of parliament, Myanmar’s military junta seized power in a coup. The country erupted in a wave of protests that has mutated into multiple forms and, in particular, a mounting movement of civil disobedience. What is at stake in this politically volatile country, where post-colonial tensions were never resolved? We spoke to David Camroux, a senior researcher at the Centre for International Studies (CERI) and a specialist in Southeast Asian affairs.

What is the background to the crisis that erupted in Myanmar more than one month ago?

David Camroux: To understand this crisis, I think we have to go back to the colonial period. Between 1886 and 1937, Myanmar was ruled by the British as a province of British India. After that, the country became an independently administered colony, before it became finally independent in 1948.

One legacy of this period is the figure of the King of Ava, who was exiled by the British after the Third Anglo-Burmese War (1886). Since then, a multi-ethnic Burma has not found a symbol of an elusivenational unity till 1988 and the return of Aung San Suu Kyi. She invokes a sense of the Burmese Buddhist notion of minluang: the “imminent king” who will bring peace, prosperity and, above all, justice.

Another important remnant of the colonial period, which continues to hold sway in contemporary Myanmar, are the ethnic divisions exacerbated by the British in order to control the country. After independence, these divide and rule tactics subordinated numerous ethnic groups to the majority Bamar people, to which Myanmar’s current leaders belong. The third legacy of British rule is a culture of Civil War that began with the Second World War and has never really died out since. When the Japanese invaded Myanmar in 1942, the majority the Bamar population initially joined the ranks, seeing their invaders as liberators who would free them from the yoke of the British. It should be noted that the founders of Myanmar’s current armed forces, the Tatmadaw, were trained by the Japanese before taking control of the country from 1962 to 1988. Among the Tatmadaw’s leaders, known as the “Thirty Comrades”, were former dictator Ne Win and Aung San, the father of Aung San Suu Kyi. However, to simplify, most of the minority ethnic groups remained loyal to the British.

Various neighbouring countries were waging wars of independence during the same period, but what distinguished the fight for decolonisation in Myanmar was that it was not a national war uniting a people against a colonial power, but rather a civil war. That war has never really ended: Myanmar has not yet managed to find a successful model of federal governance and its ethnic groups have still not found the autonomy they are striving for.

What do these tensions look like in the present day?

D.C.: In 1988, a series of demonstrations led to the collapse of the first dictatorship of Ne Win (1962-1988). These demonstrations were ruthlessly repressed with the loss of over 3,000 lives. Elections were nevertheless called but in 1990, the new military junta of Tan Shwe refused to hand over power to civilians to form a Constituent Parliament, despite Aung San Suu Kyi’s party winning a landslide victory in the elections of that year, obtaining more than 80% of the seats. A major political crisis simmered in the background till the Saffron Revolution, a series of protests led by Buddhist monks, a number of whom were killed by the army. In a highly religious country, these killings were seen as transgressing an important symbolic line and, in 2008, the military enacted a new constitution. The resulting legislation granted the military 25% of parliamentary seats, making any constitutional reform impossible without their agreement. It also gave the Tatmadaw control of three key government ministries: Defence, Home Affairs and Frontier Regions. Finally, the new constitution stipulated that anyone with a foreign family would be ineligible to run for president. This last point was significant because it was effectively designed to bar Aung San Suu Kyi, whose two sons have British nationality, from becoming president. In other words, the result was a caretaker of tutelary “discipline flourishing democracy" (sic) in which the Tatmadaw sought to control the country’s political trajectory.

While the military saw the 2008 Constitution as the culmination of democratic reform in Myanmar, for Aung San Suu Kyi and her supporters, it was only the beginning of the process. So the opposition leader and her party boycotted the election of 2010, enabling the military’s proxy party (USDP) to win an outright victory. A more reformist president, Thein Sen, was nominated. He negotiated to have Aung San Suu Kyi and 40 of her supporters enter the Parliament in bi-elections in 2012. The first genuinely free election was held in 2015, with Aung San Suu Kyi’s party winning 81% of the seats. With this overwhelming support behind her, she was able to defy the military and create a new role for herself as State Councillor. That made her the de facto president of Myanmar much to the chagrin of the Tatmadaw.

A fresh round of elections took place in November 2020, with Aung San Suu Kyi’s party winning over 80% of seats. It was a disaster for the military’s proxy party, who only took only 8% of seats top of the 25% reserved to them by law. The xenophobic dominant caste, and the state within a state they had formed, feared that their powers would be limited and their significant economic interests, challenged. So much so that at the opening of the first parliamentary session on 1 February, the army staged a coup before the new officials could even be sworn in.

One of the possible objectives for the coup is to install a system of proportional representation that would allow them to hold the majority by winning only 25% of seats that are not theirs by law.

What sets this coup apart in a national history so punctuated by political crises?

D.C.: The difference between this coup and previous ones is that it is clearly an attempt to replicate the Thai model: with the promise of a “restored democracy” and a promise of a new election within a year. The military abetted by their proxy party, and the National League for Democracy of Aung San Suu Kyi both see themselves as having an intrinsically legitimate claim to power. The crisis in Myanmar is therefore a crisis of legitimacy. On the other hand, numerous Myanmar specialists have questioned the real logic behind the coup. There are several possible hypotheses: the imminent retirement of the junta’s head, who would see the end of his chances at a legitimate takeover of power; or else a fear of Aung San Suu Kyi’s government, which has made clear its intentions of reforming Myanmar’s constitution to limit the influence of the military.

For my part, I believe that the army has made an enormous mistake, particularly in allowing itself to believe its own propaganda. That is a dangerous move for any dictatorial system because it prevents it from realising when it is actually highly unpopular. That explains why the reaction to the current coup goes far beyond a simple protest movement. What has erupted is a massive wave of civil disobedience (resignation of public officials, closure of banks and so on) that extends to the entire population: from elderly people fearing a revival of the 1988 uprising, to Generation Zs who feel their democracy has been stolen from them. Another significant factor in the revolt is the important role played by women in the so-called “sarong protests”. This is not just a revolt against a military regime: it is a revolt against the stultifying patriarchy it exemplifies.

Another factor the junta has failed to understand is that, unlike in 1988 or even 2007, the whole world is now watching them. The reason they underestimated this is because, once again, they allowed themselves to fall for their own propaganda. Added to that is the fact that the junta is not particularly skilled in a “technical” sense. To give you an example, they did not realise that they would not be able to permanently cut internet lines after the coup since the economy would collapse without a stable connection. This was something they had overlooked.

What has been the reaction on the international stage? What nations are involved and what role might they play?

D.C.: The military junta underestimated the fact that they could not count on the full support of China, who does not entirely trust them and who was benefiting from the hybrid regime in place. Meanwhile, Myanmar’s neighbouring nations are more critical of the junta and but are immobilized by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)’s principle of non-intervention. The military did not fully appreciate Aung San Suu Kyi’s international influence. What is also interesting to observe is the role of the US and EU. This major coup, arriving early on in his presidency, is a real windfall for Joe Biden in his quest to promote democracy around the world. On a different but related note, it is clear that the junta drew on the model provided by Donald Trump, in using claims of electoral fraud to justify their coup.

It has also provided a further boost for EU-US relations to have a common cause so early on in Biden’s mandate. That said, it is important to remember that, in this part of the world, Americans and Europeans only play a minor role: they can do no more than support the people, in whose hands all hope lies. They can, however, support Myanmar’s neighbouring countries, who have much greater influence: those of the ASEAN, for example, of which Myanmar has been a member since 1997. ASEAN has a legitimacy that the junta cannot afford to lose. While the Association has not condemned the coup outright, 4 of its 10 members have called for Aung San Suu Kyi and her supporters to be freed.

We can add the Chinese to this equation and the Japanese as well. The influence of the latter is often overlooked, despite the fact that the Japanese are the only ones able to make themselves heard by the military and civilians simultaneously. I was struck, for example, by the speed with which Japanese businesses were withdrawn from Myanmar – independently of politics.. Kirin just closed its Myanmar branch, for example, and Suzuki has cancelled plans for a new factory in the country.

In this diplomatic card game, the pack must be dealt intelligently: the West should play the “bad cop”, by condemning the junta morally and introducing targeted sanctions, while the ASEAN can be the good cop, using the soft power attractiveness of Myanmar membership to persuade against the military to change course. This is a Herculean task. The third players in this game, if we can call it that, will be China and Japan. Both countries could have a key role to play as intermediaries. This is especially true for Japan, whose economic clout in Myanmar no longer needs to be shown.

What are the country’s prospects in the medium-term?

D.C.: The military had banked on the support of the ethnic minorities, who have been disappointed by Aung San Suu Kyi, but this was yet another short-sighted calculation. The evidence of the last week or so suggests that a number of the ethnic insurgent armies with some 100,000 troops at their disposal are willing to ally themselves with the democratic opposition and confront the military. Ironically, it seems that the junta has succeeded exactly where Aung San Suu Kyi disappointed: in giving rise, if unintentionally, to a degree of national unity. The junta are just as mistrusted by the Bamar – who are coming to realise how extreme the mistreatment of the Rohingya has been, for example – as they are by other ethnic groups.

To take a utopian stance, it is not far-fetched to envisage a real federal democracy taking root in Myanmar after the end of this crisis. This is the proclaimed objective of a sort of government in exile, the Committee Representing the Pyidaungstu Hluttaw (Union Parliament). While the military’s repressive measures are increasingly harsh, they will not be enough to quash the resistance of the entire population – as the current one is shaping up to be. It is this widespread civil disobedience movement that has brought the economy and the administration to a standstill that poses the greatest threat to the junta. If it also has to cope with renewed armed opposition from ethnic insurgent groups on multiple fronts, then an internal putsch in the Tatmadaw may occur as in 1988, removing General Min Aung Hlaing and his clique.

Find out more: