Home>Will the Covid-19 Crisis Mark the Decline of the Populist Right?

27.05.2021

Will the Covid-19 Crisis Mark the Decline of the Populist Right?

Donald Trump’s defeat in the U.S. presidential election last November and the relative inability of populists to make their voices heard during the pandemic point to a new political cycle that is less promising for parties such as the Rassemblement National (RN) in France, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany, and the Lega in Italy.

However, we should not hastily conclude that these forces are in retreat. The issues and anxieties that drive support for those parties continue to deeply shape public opinion in Europe and the United States, and form a potential reservoir that could still play into the hands of populist entrepreneurs.

A New ‘Cycle’ of Decline for the Populist Right?

The coronavirus crisis is proving to be a major challenge for populist parties on both sides of the Atlantic. In the United States, concerns about the Covid-19 pandemic have been the Achilles’ heel of Trump’s national-populism, especially among moderate voters, who seem most sensitive to the former president’s failure to manage the health crisis.

In the United Kingdom, Boris Johnson has also paid a political price for his erratic management in the first months of the pandemic. The very limited resurgence in his popularity since December 2020 is partly attributable to a successful vaccination campaign, but it also reflects the British Prime Minister’s abandonment of populist demagoguery and his adoption of a Churchillian style in response to a worsening health situation. In Italy, the populist forces of the Lega and Five Star Movement (M5S) further moved towards political normalisation by joining Mario Draghi’s technical government last February, de facto declining to spark a new political crisis.

More generally, when in the opposition, right-wing populist forces seem to struggle to claim the narrative, as in the case of the German AfD, the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), and the Dutch populists. In France, the RN does not seem to be truly benefiting from the health crisis. Although the polls anticipate new records for Marine Le Pen, they must be interpreted with extreme caution, as the 2022 presidential elections remain relatively distant and the electoral outcome highly uncertain.The popularity of Marine Le Pen has remained fairly stable – around 30% positive – since the beginning of the pandemic. Meanwhile, the share of French people who see the RN as the main opposition to President Macron has dropped over the past year, from 43% in September 2019 to 33% last January.

In Germany, the AfD has lost ground in recent regional elections in Baden-Württemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate, losing 5.4 and 4.3 points respectively. In the Netherlands, the two right-wing populist parties – Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV) and Thierry Baudet’s Forum – held steady at their previous 2017 levels in the March 2021 parliamentary elections marked by the success of Prime Minister Mark Rutte’s People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) and the Liberal Democrats of D66.

This state of relative lethargy contrasts sharply with the previous populist cycle, which began in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008 and continued into the migration crisis of 2015. The 2014 European elections saw the emergence or consolidation of populist forces across all the political spectrum. In 2015, in a context dominated by the influx of Syrian refugees, right-wing populist groups achieved stronger results in a large number of European Union member states. In 2016, the British Brexit referendum and then Donald Trump’s victory in the U.S. presidential election testified to the vitality of a global national-populism that was still apparent across most EU member states in the 2019 European elections.

The reasons for the current populist torpor are many but essentially attributable to two major factors.

The first is the well-known ‘rally round the flag’ effect, as defined in the 1970s by American political sociology. It posits that in times of serious crisis, citizens more readily embrace parties in power. Faced with a major public health crisis, citizens seek credible political alternatives and reassuring solutions, and eschew demagogy and conspiratorial narratives of right-wing populists. As demonstrated by the CDU losses in the recent German regional elections against a backdrop of scandals about possible commissions received by conservative elected representatives in the purchase of masks, it was the incumbent Greens and SPD in power in Rhineland-Palatinate and Baden-Württemberg that benefited the most, strengthening the position of outgoing minister-presidents.

The second factor is the return of political voluntarism and the social welfare, through the many economic aid packages responding to concerns about the pandemic’s economic and social consequences. Inequality and economic insecurity are at the heart of the contemporary populist wave, these are essentially ‘mediated’ by negative attitudes towards immigration and political elites. Thus, the ‘whatever it takes' economic gamble taken at the national and EU levels addresses these concerns in the short term and may therefore provide a bulwark against their manipulation and politicisation by populists.

Under the Ashes, the Fire of Populism?

However, we should not conclude that populism is in decline. In some European countries, populist parties already seem to be reinvigorated by growing anxieties about the public health situation, as demonstrated in the recent emergence of Chega in Portugal and the Alliance for Romanian Unity (ARU) in Romania. The populist right is also on the rise in Belgium and Finland, and to a lesser extent in the Netherlands and Spain.

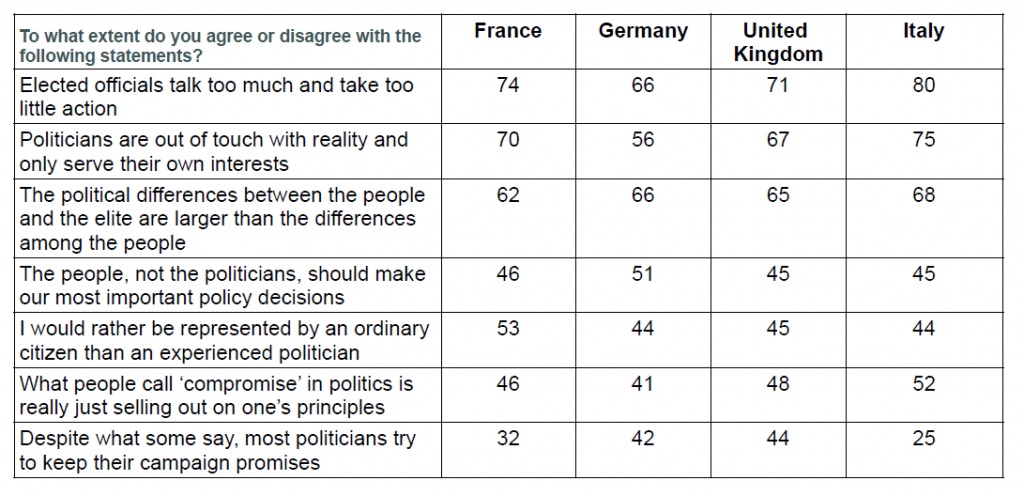

More significantly, populist attitudes remain widespread in European public opinion. Wave 12 of CEVIPOF’s Political Confidence Barometer conducted last February in France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom attests to the presence of populist attitudes widely shared by citizens in the four countries covered by the survey. The survey finds strong criticism of political elites across all contexts: more than 60% of respondents think that politicians speak too much and act too little, or that they are disconnected from reality; the appeal to popular sovereignty is paramount for nearly one in two respondents in the four countries; around two thirds of the French, Germans, Italians, and Britons feel there is a gap between citizens and their representatives, and nearly half of them say that they would prefer to be represented by an ordinary citizen than a professional politician (see Table).

Table. Populist attitudes in France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom – Detailed opinions about political leaders

Populism or the ‘Performance’ of Crises

The existence of a deep political and institutional distrust associated with such populism “from below” offers a particularly fertile ground for the criticism of elites, allowing populist entrepreneurs to instrumentalize the many economic and political grievances associated with the pandemic. Given its looming economic and social repercussions, the coronavirus epidemic has the potential to profoundly destabilise Western societies that have already been significantly weakened by the 2008 financial and economic crisis. This could pave the way for new populist successes once the public health emergency ends.

The question is whether the populist potential that we see in public opinion polls will be activated. The recent history of populism shows that the success of populist actors generally hinges on their ability to ‘perform’ crises in order to shape citizens’ perceptions. Because of their anti-establishment strategy and nationalist discourse, right-wing populist movements are able to capitalise on a vast array of economic, social, and cultural anxieties. Such anxieties are bound to arise in the post-Covid era and may fuel support for those parties. Moreover, the health crisis mainly affects the most vulnerable social groups, in the working and lower middle classes, which traditionally form the bulk of the populist right’s electorate.

In the longer run, the impact of the public health crisis may also be felt in the legitimisation of some of the right-wing populists’ key issues and themes. Concerns about the pandemic have fuelled demand for protection, safety, and strong leadership, and they have also brought key populist issues of borders, sovereignty, and the protection of national interests to the forefront of the political agenda, which resonates with the many economic and cultural insecurities produced by globalisation.

Finally, compounded by the consequences of climate change and the explosion of extreme poverty in the most fragile countries, the pandemic is likely to intensify migration flows in the future, putting immigration back at the heart of the political agenda, to the benefit of the populist right.

Data from the latest wave of the Barometer of political trust illustrate the presence of a set of authoritarian, nativist, and socio-economic attitudes which align with the nationalist and anti-globalization protectionist ideology of most right-wing populists: around 60% of citizens surveyed in France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom think there are too many immigrants; more than 70% think income inequality should be reduced; between 30 and 40% think their country should protect itself more from the world; and around 45% embrace the idea of having ‘a strong leader who does not have to worry about the parliament or elections.

In light of this data, a new political ‘cycle’ marked by a lasting decline of populism still seems highly unlikely.

This article was written by Gilles Ivaldi, CNRS research fellow at the CEVIPOF. It was originally published in Sciences Po's research newsletter, Cogito.

Learn more: