Home>The Women Who Made Sciences Po

23.08.2019

The Women Who Made Sciences Po

Originally featured in BIM, Sciences Po’s internal publication, this article was written by historian and researcher Marie Scot.

In 1904, three young women applied to the Ecole libre des sciences politiques, causing Emile Boutmy to seriously consider the “movement [...] shifting public opinion in regards to women’s education [...] Would it be prudent to resist such a movement? Would it be fair to thwart its progress?”

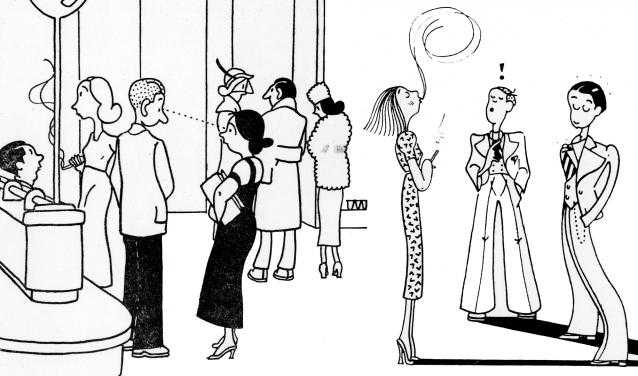

Ahead of his time, Director Emile Boutmy recommends that they ought to be admitted, but only after “a careful and discrete investigation” to ward off “loose women whose sole aim would be to seduce sons of good families who make up the majority of our students, and curious women who would attend in the same way one does a pleasure party.” Nevertheless, women would have to wait until 1919 before the doors would half-open for them; six women, five of whom were foreign, were admitted. Women were subjected to a discriminatory entrance exam, and they were scarcely encouraged to apply. They represent less than 10% of students before 1939 as “one moderately pretty young girl, could mean that five young men will not work” according to André Siegfried’s famous “theorem”.

The thorny “question of women” would crop up again in 1945: “Shall we admit women via the entrance exam or the concours in exactly the same way that we do men?” Some members of the School’s Board of Directors want “to conserve the special entrance exam, no matter the cost”, whilst others fear “an invasion”. “Could we not restrict their numbers?”, they asked. Thankfully, common sense prevailed for the majority: “women have the vote and are eligible, you can not maintain such restrictions.” Slowly, Sciences Po’s student body would become more female, reaching 20% after the end of the war, then 25% between 1950 and 1960, and barely more than 30% at the start of the 1980s. It would only be with Lancelot’s 1989 reforms, which favoured “direct entrance” based on a “mention Très Bien” (highest honours) on the baccalaureate, that the female student population would reach 50% in the late 1990s, and surpass it in the 2000s.

Women were equally silenced on the professional side of Sciences Po, from the inter-war period right through to the 30 Glorious Years. Suzanne Bastid, Professor of International Law, became, in 1941, the first and only woman to teach a core lecture until 1968, when Hélène Carrère d’Encausse was appointed. Between 1973 and 1995, only around 10 women (4%) were lecturers of cours magistraux (core lectures). Similarly, there were only six women who taught elective courses before 1968, around 20 before 1980 (6%) whereas their numbers increased by a quarter in the 1990s. Almost absent from the lecture halls of the IEP, there were more women in the research centres. Among them, for example, were Michèle Cotta, Nicole Racine, Odile Rudelle, Janine Mossuz-Lavau, Colette Ysmal, Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, Marie-France Toinet… who paved the way at the end of the ‘50s. There is nothing surprising about the fact that these researchers were pioneers in the field of gender studies. Nicole Racine put female intellectuals into the historical narrative, whilst Janine Mossuz-Lavau studied, from 1966 onwards, gender politics and contraception, and published in 1976 with Mariette Sineau a large study on women in politics. Neither reactionary nor pioneering, Sciences Po became more female at a slow but steady pace, developing at the same rate as French society. Despite some notable and enduring exceptions, the battle for gender diversity is now mostly behind us; but is the fight for gender equality truly won?

More information

- A History of Women : 5 key dates in women's history at Sciences Po

- Gender Equality at Sciences Po

- 8 Ways Sciences Po acts to advance gender equality