Home>Sciences Po and Women: Throughout the Years

07.03.2022

Sciences Po and Women: Throughout the Years

Neither trailblazer nor latecomer, Sciences Po has evolved in line with advances made by women in the workplace throughout French society. In the 2000s, female students even surpassed in number their male counterparts; women now account for 60% of all students at Sciences Po. A little over a century after the first female students walked through the doors at the École Libre des Sciences Politiques, we take a look at their history within the institution.

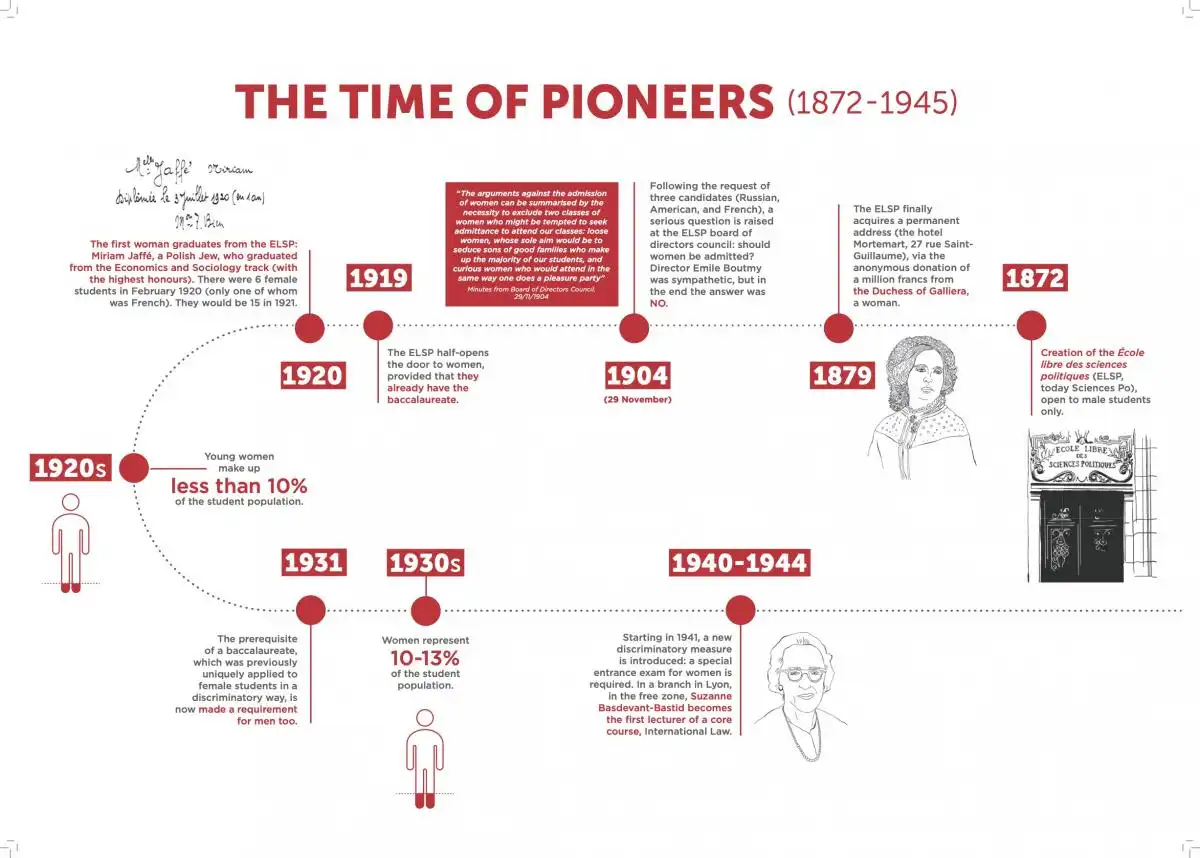

The story of women’s involvement at the school began just a few years after its founding. A donation from the Duchess of Galliera, 140 years ago, paved the way for the institution's permanent move to rue Saint-Guillaume in 1882.

The question of admitting women was first raised in 1904, when three female prospective students applied to the École libre des Sciences Politiques, still reserved for men. Despite being favorable to their integration, Director Émile Boutmy remained cautious: he wished at all costs to exclude "loose and flighty women whose design is to start relationships with the sons of good family who people our lecture halls, and the curious-type women who would treat their schooling like another leisure activity." Other prominent figures at the school were even more reluctant and strongly opposed integrating women, citing Siegfried's theory: "For every decent-looking girl, there will be five boys slacking off." Ultimately, the Board of Trustees were convinced that women could prove a distraction to male students. Thus, the campus would remain closed off to women until the end of World War I.

A Gradual Integration

In 1919, women finally became eligible to apply, but they were still subject to a discriminatory selection process: in order to study at rue Saint-Guillaume, they had to have passed the baccalaureate, unlike their male counterparts. The first female students made a quiet debut. Out of the seven admitted, five were foreigners. The first female graduate, Miriam Jaffé, graduated in 1920 with honors. By 1921, there were 15 female students. Their number gradually increased, though never rose higher than 10 to 13% of the student body during the inter-war period.

Foreign-born women predominated in the Diplomacy section, while French women preferred the so-called General section. In 1931, the admission requirement for the École libre des Sciences Politiques (holding a baccalaureate), previously a discriminatory barrier for women, was extended to male students. But a new condition was to be imposed on them during the Second World War.

While the École libre des Sciences Politiques continued its activities during the Occupation, a special admission exam was made compulsory for young women starting in 1941. At the time, only 3 to 4% of students were female. It was ironically at that time that the status of women at the school made a sizable forward stride: Suzanne Basdevant-Bastid became the first female professor to teach a core curriculum subject (International Law) at the satellite campus established in the wartime Zone Libre city of Lyon.

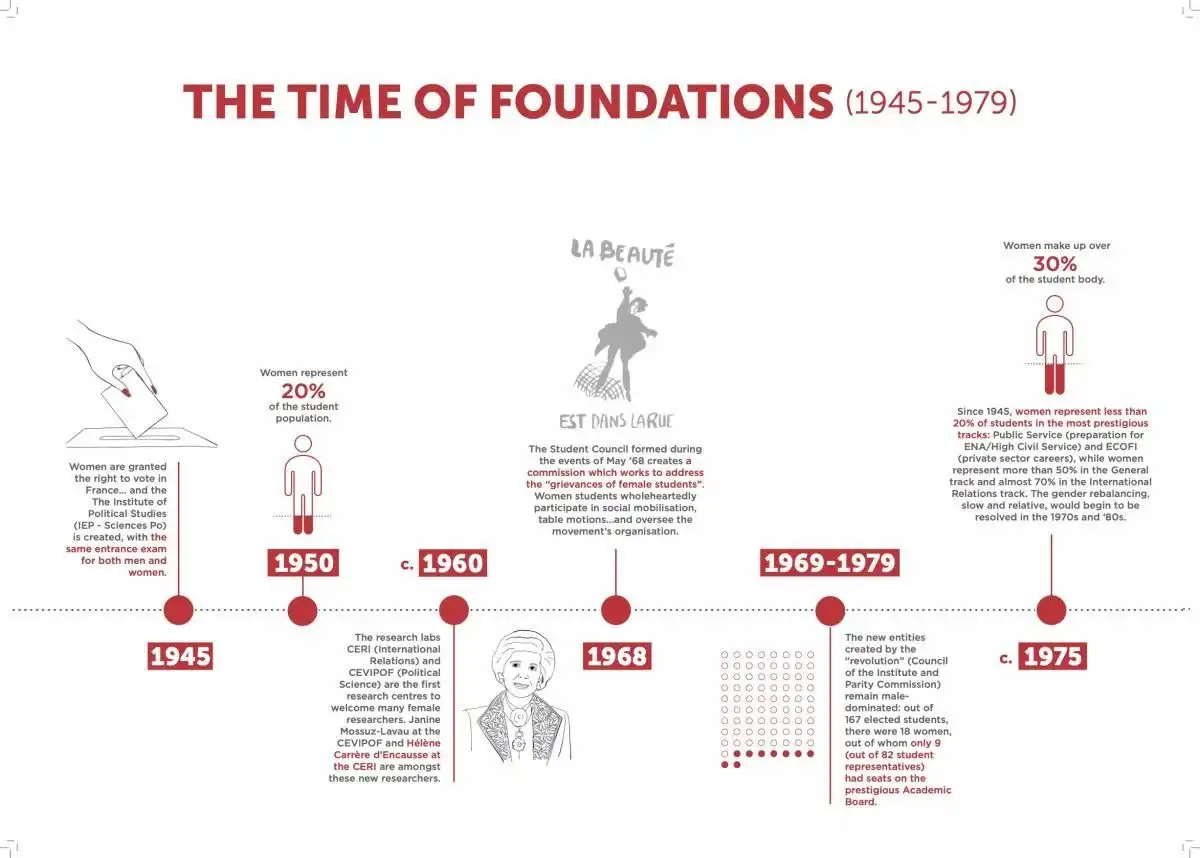

The year 1945 marked a turning point: women were granted the right to vote and the École libre des Sciences Politiques was replaced by the Institut d'études politiques de Paris. That same year, artist Gaston Pirou prevailed upon the institution to lift its cap on female enrollment. Pirou asserted that women "are electors and eligible" and that, henceforth, there were no grounds for limiting their numbers. All applicants, regardless of their sex, were from then on evaluated using the same entrance exam.

By 1949–1950, women accounted for 20% of the student body. Bit by bit, they were becoming students like any others. Yet, even after graduation, women were hard pressed to escape stereotypes relegating them to clerical positions. On the teaching front, the presence of women within the institution had languished since the arrival of Suzanne Basdevant-Bastid, who would remain the school's lone female lecturer until 1968.

The Era of Conquests

The question of gender equality came to the fore in the 1960s, extending beyond educational opportunities. This was also the period when women joined the Sciences Po research community. The Center for International Relations (CERI) and the Center for Political Research (CEVIPOF) welcomed several female researchers, including Hélène Carrère d'Encausse and Janine Mossuz-Lavau.

In 1968, Student Council commissions set out to address the "problems of women students". These discussion groups enabled women to take on greater visibility within academic life, though the bodies set up for this purpose were still predominantly male. From 1969 to 1979, only 18 of the 167 elected students were women.

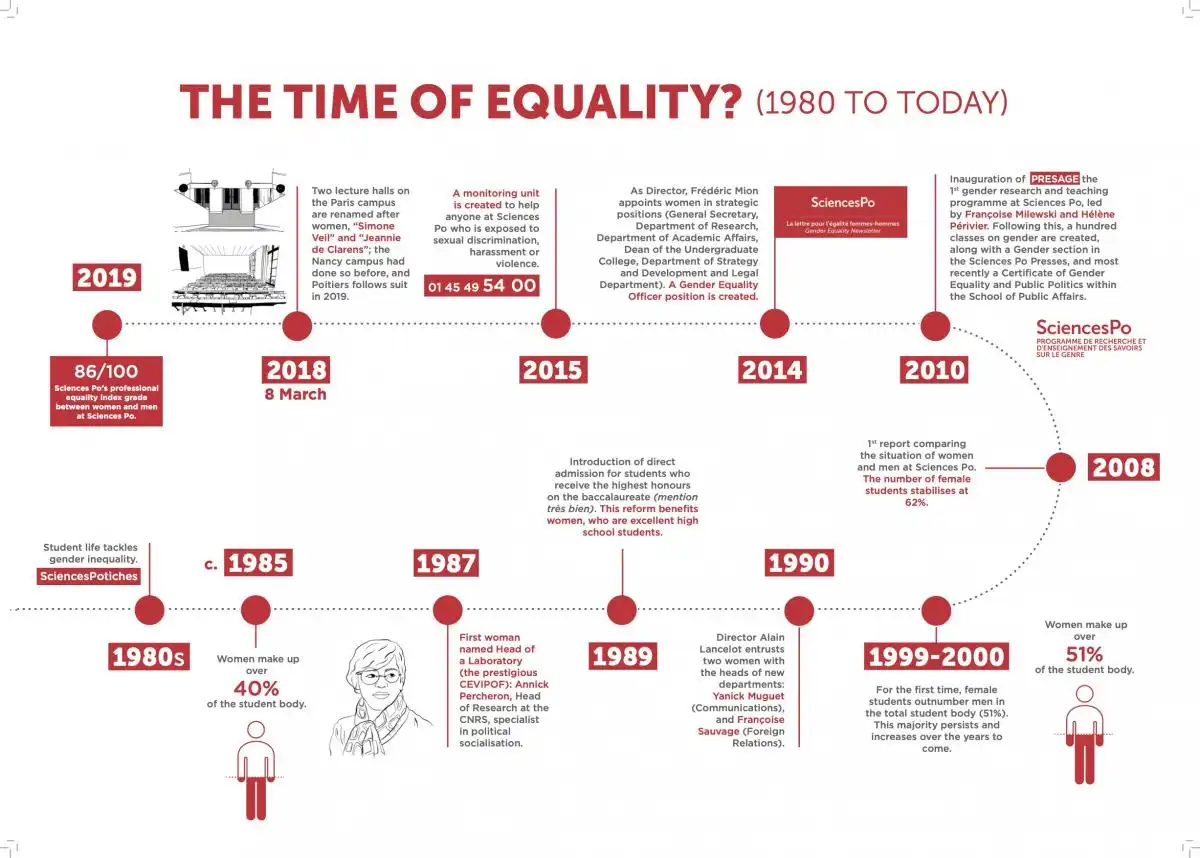

With regard to research, the first woman to be appointed laboratory director was Annick Percheron, research director at CNRS and specialist in political socialization. In 1987, Percheron was promoted to the head of the prestigious CEVIPOF.

Equality At Last

Despite getting off to a rocky start, one trend is certain: since the 1930s, the proportion of female students has slowly but surely climbed. In the 1930s, 10 to 13% of students were women, by the end of the 1940s, about 20%, and by 1975, 30%. The number of women in higher education still lags below the national average of 47.5%, according to the Observatoire des inégalités.

The number of female students gradually increased, reaching 51% in 1999, thanks in particular to the 1989 reform of admission procedure, granting entry to applicants having earned the "très bien" distinction on the baccalaureate. Since then, the number of female students has increased year on year. Women have managed to be enrolled of the school’s academic sections, including the most prestigious and historically male-dominated among them.

At Sciences Po, the 2000s were shaped by proactive policies fostering gender equality. In 2010, Hélène Périvier and Françoise Milewski created PRESAGE, Sciences Po’s Research and Educational Program on Gender Studies. The impetus achieved has led to the creation of a hundred or so courses on gender, the introduction of a “Gender” field at Sciences Po University Press and, more recently, the creation of a Gender Equality and Public Policy Certificate at the School of Public Affairs.

Following his appointment at the helm of Sciences Po in 2013, Frédéric Mion asserted his intent to lead by example when it comes to gender equality. A task force devoted to this issue was formed within the school's General Secretariat, with women appointed to strategic positions: General Secretary, Scientific Director, Director of Studies and Student Success, Dean of Sciences Po College, Director of Strategy and Development, and director of Legal Affairs.

In 2015, a support hotline was set up to assist any Sciences Po employee having experienced sexual and gender-based violence. Last but not least, the names of two celebrated graduates, Simone Veil and Jeannie de Clarens, were chosen to adorn two lecture halls on the Paris campus; the news was announced on March 8, 2018, in honor of International Women’s Day.

Originally by historian Marie Scot and the editors of Émile magazine.

The Sciences Po Editorial Team

Find out more

- About Sciences Po's action in the field of gender equality

- About the Women in Business Chair

- Explore the history of Sciences Po

- Discover Professional Equality Week