Home>How "sanctuary cities" in the US stand up to Federal immigration enforcement

29.10.2018

How "sanctuary cities" in the US stand up to Federal immigration enforcement

Targeted during President Trump’s presidential campaign and directly threatened in his ensuing executive order in January 2017, the topic of sanctuary cities has resurfaced to the forefront of political debate in the past year. Although there is not one single definition of what it means to be a sanctuary city, sanctuary cities are generally characterised by a general declaration of support by a city’s leaders for its residents, and in particular undocumented residents. More ambitious sanctuary policies seek to limit how local law enforcement agencies cooperate with federal immigration enforcement.

With a shift toward harsher and more restrictive immigration policies at the national level, American sanctuary city policies represent an innovative response by local jurisdictions exercising their role to test new social and economic experiments within the laboratory of federalism. Such policy experimentation and understanding what it entails is also key to comprehending the current immigration enforcement debate happening in the United States, and echoed in many other parts of the world.

Historical context

The term “sanctuary city” was first developed during the 1980s in the United States as a response to the treatment of Guatemalan and Salvadoran refugees by the federal government. Despite the presence of civil wars in both countries, few asylum seekers from Guatemala and El Salvador were granted refugee status in the United States. Instead, they were labelled as “economic migrants” and as a result of the denial of their requests, faced imprisonment and deportation by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS, later replaced by ICE).

As the US government attempted to justify its refusal of refugee status through criminalising techniques and rhetoric, refugee advocates and activist groups also began to respond, especially when reports from organisations like the ACLU publicly revealed the number of deportees who were killed after deportation, in addition to the harsh conditions at INS detention centres. These reports and testimonies helped to spark the first Sanctuary Movement, originally led by a group of religious organisations in California and Arizona. These organisations were later joined by universities, civil rights groups and human rights organisations.

Under the umbrella of the Sanctuary Movement, local governments in favour of the movement began to provide resources to the organisations involved, and eventually began passing sanctuary city policies aimed at limiting support for the policing work enacted by the INS. Within three years, from 1984-1987, 20 cities and two states passed resolutions to provide sanctuary for Central Americans, many including “statements of non-cooperation with the INS.” One of the most significant sanctuary cities to come forward at this time was San Francisco, which in 1985 passed its first resolution as a “City of Refuge,”. In 1989 it passed its first sanctuary city ordinance, making it the only city at that time to go beyond symbolic resolutions and statements and to issue a specific law related to the protection of immigrants.

The new sanctuary movement: Santa Ana, California

There is not one sole definition of what it means to be a “sanctuary city.” Rather, as the historical movement has shown, sanctuary cities encompass a range of different policies and political statements, ranging from symbolic formal declarations of a city leader’s support for its residents with and without papers, to more concrete policy ordinances like a refusal to comply with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detainer requests or to utilise local resources in deportation efforts. While there has been some political and media attention about whether or not sanctuary cities or states comply with immigration law, the carefully worded language found within state and local sanctuary ordinances, and reinforced by a string of judicial decisions, reveals that these states and city ordinances clearly explain how they act in accordance with the law, and clarify that they only refrain from cooperating where compliance is voluntary.

In January 2017, the city of Santa Ana, located in Southern California, became one of the newest cities to pass a sanctuary city resolution and legal ordinance. The city has a long history with immigration, and today hosts a population that is 78% Latino. Because of this, local community members have felt a direct effect of discrimination from migration policies and local policing which have directly targeted Latino immigrant populations.

The national and local media coverage of Santa Ana following the passage of its Sanctuary City Ordinance both revered, and criticised the city as having passed one of the most ambitious and far-reaching sanctuary ordinances in the country. While many articles praised the city for its resolution, the struggle to implement the ordinance remains ongoing. The ordinance called for broad commitments to “implement policies to prevent biased-based policing”, to promote “social justice and inclusion” for all residents, including its immigrants, and to establish a commission or task force to carry out these policies.

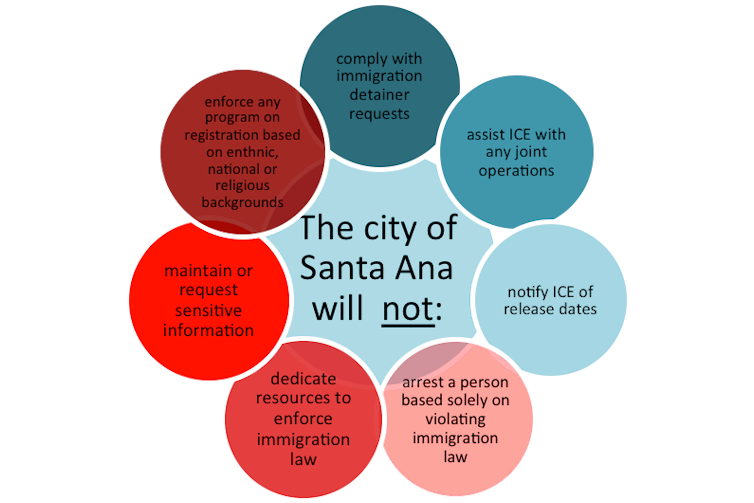

The initial Sanctuary Resolution issued a series of ambitious, but mostly symbolic statements. However, on January 17, 2017, the city approved an ordinance which turned the resolution into law. This also meant that the more concrete provisions established in the resolution were now part of a contractually enforceable city ordinance. The ordinance laid out the following central provisions for the city to implement:

It is also possible to explain sanctuary cities’ actions in terms of costs to the cities. In the case of ICE detainer requests, for example, a series of lawsuits questioning the legal legitimacy of the policy have resulted in financial costs to cities. Court decisions in these cases have resulted in the city owing damages to individuals for being held beyond the established legal time frame without probable cause. In addition to challenges tied to the legal legitimacy of the program, lack of moral legitimacy affects community relations with city officials. Police actions related to immigration enforcement also have a negative effect on public health and education, for example, when families are afraid to have their children vaccinated or attend school for fear of deportation of themselves or another family member. Because of this, city officials in favour of sanctuary policies believe that by disentangling local officials from immigration enforcement, their cities become safer places for residents to live and work.

In Santa Ana, we can observe how grassroots mobilisation and local activism played an important role in garnering support for the Sanctuary City Ordinance. Just as activists responded to what they believed was an unjust policy in the late 1980s toward Central American refugees, local advocacy groups and associations were again essential in creating the push for a new sanctuary movement. The transformation from grassroots activism to policy reveals how collaboration between community members, legal organisations and law schools, non-profit organisations and city councils can produce tangible policy outcomes. While their tactics can take the form of protests, city-approved working groups and information sessions, these local actors all work within the realm of the federal system.

As immigration takes centre stage in global politics, immigrants are subjected to political manipulation on both sides of the political spectrum. Coupled with the trends of globalisation and growing urban populations around the world, cities increasingly represent laboratories for our societies to come to terms with immigration, local identity, diversity and integration. Ultimately, by analysing immigration policies of cities and their local governments, we may be able to arrive at a deeper understanding of how to promote better governance and more inclusive societies as a whole.

More information on sanctuary cities is available in the full-length article.![]()

Jennie Cottle, PhD candidate in Political Science, specialising in immigration policy and enforcement, Sciences Po – USPC

This article was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.