Home>Beyond picture postcard Paris

01.03.2017

Beyond picture postcard Paris

The class “Paris dans la littérature” is offered during the Sciences Po Summer School's University Programme in July. The class draws on literary sources to examine the historical, cultural and social forces that have shaped Paris through the centuries. Interview with the two professors who teach the class.

What is the most important thing that students in your class "Paris dans la littérature" will learn?

Christophe Reffait: I hope that we will go beyond “picture postcard Paris” to examine the various cultural, political, economic and social factors that have contributed to shaping the city. By the end of the course, students will have gained a familiarity with Paris that will allow them to appreciate the richness and depth of its history. For example, they will learn how the boundaries of Paris developed and how these were described by 19th century authors; they will learn when certain avenues were built and gain an understanding of the architectural homogeneity of the city.

Matthieu Vernet: They will learn to see Paris and its portraits in literature as complex and multi-layered; constructed over time and of their time. This mix of timelessness and immediacy seems to me to be the richest and most important element of literature. Furthermore, Paris is a remarkable observation point, as, rather like Rome, the city is full of traces of past lives that only reveal themselves when the layers of its history are examined and brought to light.

What is your favourite book situated in Paris?

Vernet: In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust. It’s a long and challenging novel, but one of the most important works in world literature. It isn’t a book about Paris, but it is situated in Paris during the Belle Époque, at a time of great change, before and after the First World War. Proust describes the changes in what was at the time considered to be the greatest capital in the world. These changes appear not only in the streets, in social interactions, and in technical progress, but also in man’s changing relationship with himself. It’s a life-changing novel.

Reffait: I’m not sure if I have a favourite “Parisian” book. Sentimental Education (1869) by Flaubert, perhaps. What interests me most are the glimpses of Paris we get through literature, starting with Le Roman Bourgeois by Furetière in 1666 and continuing with the novels of Modiano and Echenoz today. Bygone detective novels, such as those written by Emile Gaboriau in the 19th century, are treasure troves of information about everyday Parisian life, even though they don’t necessarily have the detailed descriptions found in Zola’s novels. In fact, it seems to me that the question should be the other way around: Paris is made up of favourite books. A sketch of Parisian rooftops by Verlaine, a stroll through the streets by characters from Flaubert or Zola, a woman’s shadow by André Breton: these are the things that create Paris.

What advice would you give to a student who is coming to Paris for a summer in order to improve their French? And what tips would you give them for exploring the city?

Vernet: Contrary to the stereotype, Parisians are much more talkative and curious than they might seem. I recommend that students go exploring in the neighbourhoods of Paris, that they get off the beaten tourist track and become flâneurs like Baudelaire, Hemingway and Walter Benjamin. They can get to know the unseen side of the city by opening doors, asking questions, or even by just sitting on a bench and watching the world go by.

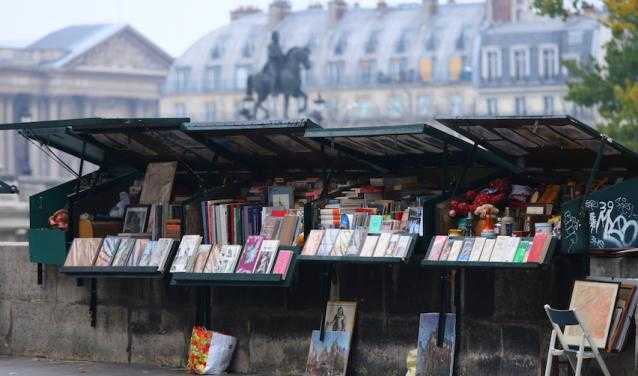

Reffait: I think that improving their French and exploring Paris go together, and both require students to set very simple and specific goals. For example, eat lunch at a café counter and listen to the customers’ conversations; go shopping at a bakery, a butcher's, or a fishmonger's rather than at a supermarket; go to a bookstore and ask them to recommend a contemporary novel; go to an antique store in the vicinity of Sciences Po and ask for information about a particular object; get a length of fabric cut at the Saint-Pierre fabric market; buy a ticket to the theatre, and so on. These everyday situations require significant linguistic abilities. They also require students to spend some time alone in the city, without their Summer School friends, in order to immerse themselves and force themselves to speak French.

You have both taught at the Summer School for several years. What are you most looking forward to about this summer?

Vernet: The first day and meeting the students. Since I began teaching at the Summer School, this has always been a fun and exciting moment. The students, who come from all over the world, are enthusiastic and happy to spend part of their summer in Paris. It’s an important moment of exchange when everyone says: this month is going to be exciting.

Reffait: I enjoy the moment a few days after the start of class when the students get into the habit of eating lunch together as a group in the garden or on the banks of the Seine.

Related link