Home>Emmanuel Macron, French president-elect, Class of 2001

05.05.2017

Emmanuel Macron, French president-elect, Class of 2001

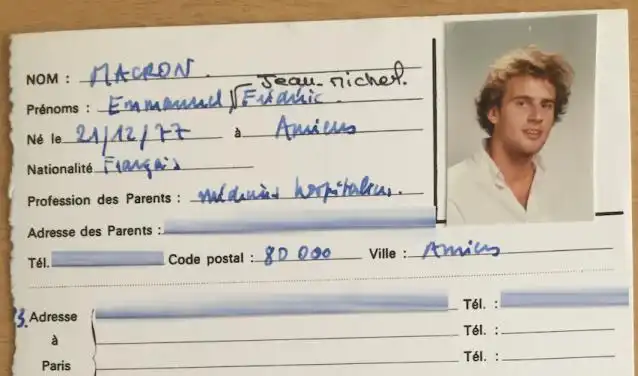

Emmanuel Macron was 21 years old when he arrived at Sciences Po. After three years of preparatory classes in the arts section at lycée Henri IV and two failed attempts at the entrance exams for the École Normale Supérieure, he is said to have gone to Sciences Po to “lick his wounds,” perhaps even “with a certain spirit of revenge”. In any case, he was recommended by his prépa professors in his application for Sciences Po as a “likeable” candidate “who inspires confidence”, and an “enthusiastic and lively personality”. His plans for the future were still wide open, but thoughts of a career in higher education, “possibly abroad”, prompted him to choose the International section (one of four programmes offered at the time).[1]

“Public service” and political philosophy

Macron’s time at Sciences Po, though often reduced to a one-line mention between his preparatory studies in the Latin Quarter and his years at the École nationale d’administration (ENA), was in fact a more decisive period than it may seem. First of all, for his choice of a public career. At the start of the third year of what was then a three-year degree programme, he swapped sections to join the Public Service section. He spread this third year over two years so that, in parallel, he could complete his studies in philosophy at the University of Nanterre. There, he earned an honour’s and a Master’s degree with dissertations on two political philosophers, Machiavelli and Hegel. To round out his timetable, the busy young man became editorial assistant to Paul Ricœur for his book La mémoire, l’histoire, l’oubli, published by Seuil in 2000.

“Obvious aptitude”

This didn’t get in the way of him being a brilliant student at Sciences Po, and he just kept improving. Was this a sign that he had made the right choice with the Public Service section, or that spreading his courses over two years meant he could better reconcile all his academic commitments? In any case, the year he earned his Sciences Po degree, he got the top mark in his “Advanced Economics”, “Political Issues” and “Public Finance” lectures. The assessment by his professor for the “Social Protection” course— “a brilliant pupil”, “very mature” with “original and well-constructed thinking” and an “obvious knowledge of the subject”—set the tone. Most professors sung his praises, particularly stressing his “obvious aptitude for public speaking, as much in substance as in form”. His involvement in drama since his high school years, complemented by workshops at Cours Florent drama school, was suitably appreciated at Sciences Po, the university where eloquence is king.

Meetings that count

Young Macron clearly liked to talk, but not to hold forth. “He was the best student in my lecture,” recalls Ali Baddou, who was one of his teachers, “but I especially remember that he loved to ask questions, to discuss things.” The Sciences Po appariteurs—campus porters in constant contact with the students—have a similar recollection: “he was close to us and would always come over to talk.” Another of his professors, historian François Dosse (who introduced him to Paul Ricœur), stressed “his ability to summarise and link different classes and reuse the material”² and that he was “constantly leading debate in the group, always at an excellent level”.

The conversation begun at Sciences Po with his professor Jean-Marc Borello has been going on for seventeen years. This social economy entrepreneur (SOS group, 15,000 employees) is now one of the pillars of En marche! (FR) The same is true of Macron’s former classmate Aurélien Lechevallier, with whom he studied for the ENA entrance exams and who is now his international affairs advisor; of Benjamin Griveaux (class of 1999), now spokesperson of En Marche; and not to forget his close friend, economist Marc Ferraci, now his economic advisor. These connections and friendships have obviously lasted longer than his passing interest in Jean-Pierre Chevènement’s movement. Macron attended the party conference of the Mouvement des Citoyens in Perpignan in 1998 and in 2000 he interned in the office of George Sarre, mayor of the 11th arrondissement and a close supporter of Chevènement. “The adventure was to end there,” writes Nicolas Prissette in his book on Macron.¹

“Moral elegance” and “a very friendly spirit”

His relationship with Sciences Po, on the other hand, has never ended. Fresh out of ENA, and “while the other members of the Inspection Générale des Finances traditionally return to give economics classes at the Republic’s elite schools,” writes François-Xavier Bourmaud, “he chose to teach ‘general knowledge’ at Sciences Po”.[2] A few years later, Macron would show himself to be equally generous with his talents as an orator for the next generation of Sciences Po students: he was guest of honour at the 2015 graduation ceremony and returned three times in 2016, for the student Gala evening, the Paris School of International Affairs symposium (a debate on Europe) and... the send-off for a retiring appariteur he had befriended.

At Sciences Po, before his mastery of rhetoric had been honed by experience, his enthusiasm and aptitude for writing occasionally made him a little too voluble; “too long” appears in red pen on several of his papers. Another (minor) failing of this exemplary student was “a tendency to be too sure of himself”, as one teacher noted, “counterbalanced by a very friendly spirit”. But it is probably the assessment of one of Sciences Po’s main professors of the history and law of states that best reflected young Macron’s potential: an “exceptional student in all respects”; “a lot of intelligence and moral elegance”; “real generosity. An uncommon intellect.” The title of the course the student so excelled in? “The French State and its Reform”.

- [1] Quoted in “L’ambigu Monsieur Macron”, Marc Endeweld, Flammarion (2015), page 50.

- [2] Macron, l’invité surprise, François-Xavier Bourmaud, l’Archipel (2017)