Home>Crimes of Fashion: How the Laws of Western Clothing Have Changed (and Remained the Same) Throughout History

08.12.2021

Crimes of Fashion: How the Laws of Western Clothing Have Changed (and Remained the Same) Throughout History

From Louis XIV to the Black Panthers, from Queen Elizabeth to the flapper—the ways in which different groups throughout history have dressed has never been neutral. Stanford University’s Richard Thompson Ford and Sciences Po’s Marie Mercat-Bruns take the conversation a step forward by discussing fashion and power in both the old and new world.

On Tuesday, November 16th, Sciences Po and PRESAGE hosted a discussion with Richard Thompson Ford—Stanford University professor and expert on Civil Rights and Anti-Discrimination Law. Ford took the occasion to present excerpts from his new book, Dress Codes: How the Laws of Fashion Changed History and explore key ideas with Sciences Po students.

An unlikely subject with an enormous amount of cultural and political meaning, clothing—and the people who wear it—took center stage. Sciences Po Professor Marie Mercat-Bruns began the discussion by noting that:

“There is much more than meets the eye. Fashion and appearance is not trivial—it is about human beings.” If clothing is about human beings, it follows, therefore, that it is also about laws, about sociability, and about class dynamics. These are precisely the dynamics that Ford would go on to analyse throughout his talk.

On the Use of Sartorial “Tools”

“Fashion is a tool,” asserted Richard Thompson Ford, “It can be used by many different groups of people for different purposes, and has been.”

The various cultural, racial, gendered, and geographical groups discussed throughout the talk have used—and continue to use—this tool as a means of either maintaining the social and political status quo or of undermining it.

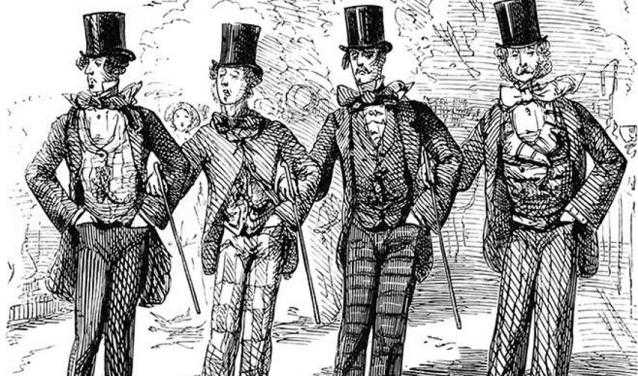

Indeed, throughout history, as Ford pointed out, clothing and laws pertaining to clothing have been used to control the expression of social status—laws reserving red-soled shoes for the French monarchy, for example, or the ban on “all new fashions” in Venice in 1551—as well as to disrupt social norms and status, as with the “Sunday best” worn by protesters at the 1963 March on Washington.

Since clothing signifies, its signification is intended for a particular audience—which is to say, those around us, our neighbors, friends, and enemies. Yet its significance stretches beyond the collective, touching us as individuals and intertwining itself with identity itself.

From the Collective to the Individual

What does an increasingly globalised world, where renewable fashion and vintage shopping are changing the face of the industry, mean for us today? According to Ford, these new phenomena—following a trend of individualisation and expressiveness that began in the Middle Ages—allow “for more individual control and creative freedom” when it comes to our ways of dressing.

From the queer community, to historically marginalised racial groups, to women and the working class, fashion has been used not only as a political tool, but as a representation of the self—of personal dignity and an expression of individual worth in the context of society.

Does this mean that we are witnessing a democratisation of fashion in an era in which the rules of fashion are less and less explicit? Only time will tell. But until then, as Ford notes, “the expression of identity has been one of the defining features of Western fashion” and we are the ones who will decide where it goes from here.

The Sciences Po Editorial Team