Statehood in the Middle East and North Africa. Approaches from Historical Sociology, Part II: Conceptualizing and Measuring Statehood

Conceptualizing and Measuring Statehood

In part I of this paper, I argued that comparing levels of statehood was an important part of understanding the MENA state and that historical sociology gave us the tools to do this. But to compare we have to be able to measure “degrees of statehood.”

One approach would be to measure state performance by examining outputs: relative ability to extract resources (taxation) and to deliver public goods relative to resource endowments, beginning with security, but also generally expected to include education, health (measured by Human Development Indicators), infrastructure etc. The advantage of this approach is that reasonably reliable quantitative indictors are available to allow comparative measurement.

Another way to approach this, as prefigured in part I of the paper, would be to focus on appropriate structures that arguably explain this output performance. In Weberian historical sociology, this is measured by comparison against an ideal type of Weberian state. In Michael Mann’s work (1984, 2008, 2014), state-building combines advances in the centralization of power, providing the ability to make binding legitimate decisions, together with “infrastructural power”—the ability to penetrate society, implement policies, and exercise a monopoly on legitimate violence in the state’s territory. Mann calls the centralizing dimension “despotic power”, denoting the ability to make decisions without being constrained by powerful social forces. While this may be appropriate where modernizing states need to overcome resistance from entrenched privileged interests, if pushed too far, it suggests an unaccountable state liable to abuse its power. The security that states are expected to deliver means protection from other states and law and order among groups inside a country; but it also means security from the state itself such that it does not itself become predator or parasite on society.

This dilemma is addressed by the work of Huntington (1968). For him, state formation advances along two varying dimensions: institutionalization and participation. Institutionalization on the policy-making side signifies that the political sphere has its own rules that regulate the behaviour of social forces in the political process, e.g. decision-making rules such as majority vote, division of powers, or checks and balances among state institutions, designed to safeguard their autonomy and guard against capture by any one social force including the ruling elites. This requires some recognized distinction between the regime’s interests and those of the state; it also requires state institutions to be strong enough to constrain political elites.

On the policy-implementation side, institutionalization means a move from patrimonial to legal-rational practices. Specifically, it means rules by which power-holders are constrained by rules of office, such as limited jurisdictions, recruitment on merit, and impartiality in the application of rules, etc. It also implies that office holders have a sense of loyalty to the public interest and do not merely represent the social force from which they are recruited, whether it be class, tribe, or communal group. Penetration of society and policy implementation will fail if local state offices are colonized by the dominant social forces of the region, resulting in nepotism, favouritism, arbitrary application of rules, resistance to the centre, and the incapacity to either extract resources (taxation), or to deliver public goods, including predictable rules. When the state structure is built from patrimonial practices rather than a legal-rational bureaucratic chain of command from the centre, local notables are co-opted into a bargaining relation with the state in which they may, for example, act as tax farmers and gatekeepers (mediators) between the centre and the more powerful local forces such as big landlords, most likely at the expense of the lower classes.

A second part of Huntington’s argument is that, in order to both allow political elites to be held accountable and to mobilize consent for policy implementation, institutions must incorporate citizen participation. This means bureaucratic “output” structures must be balanced with political “input” infrastructures. And as the population becomes increasingly politicized—with the public expanding from small oligarchies to include the “new middle class” and then the worker and peasant masses—robust statehood requires they be incorporated into political institutions with rights to citizenship and political participation. If this does not keep pace with the expansion of politicization, social forces will engage in various forms of “praetorianism,” that is, they will attempt to use their resources to directly shape outcomes untempered by political rules. They may for example resort to violence, or the threat of it, and the rich may use bribery and other forms of corruption to impact law-making or gain exceptions from law. The more political mobilization exceeds institutional incorporation of social forces, the greater the likelihood of instability, coups, or even revolution.

In summary, statehood implies two dimensions, the autonomy to make decisions incorporating public interest broader than mere particularistic ones and the capacity to implement decisions delivering public goods. Needless to say, developing indicators to operationalize each dimension—level of autonomy of the centre, infrastructural power, overall institutionalization—would be very challenging. If such measures were developed, they could be tested by comparing the different states of the region and seeing how far structural variations account for output performance. This is not likely to be precise, however, and attempts to reduce the complexity of country cases to a few measurable indicators are not likely to yield much in themselves. However, if one were to find interesting associations as a result of such efforts—notably between structural development and enhanced delivery of public goods—then these could be explored by case studies using a process tracing method to understand the causalities at work.

Variations in Statehood: Toward a Typology

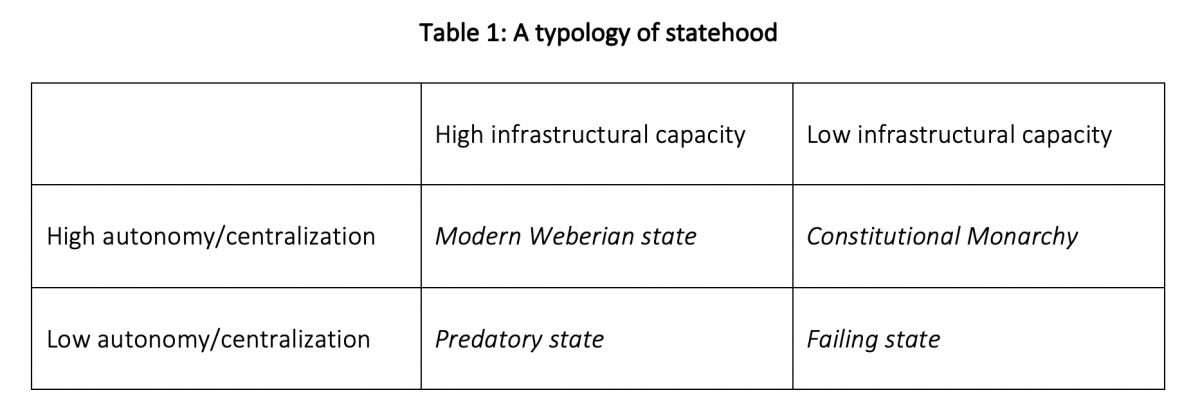

An important step prior to or as part of such an attempt at measurement would be to arrive at some rough classifications—a typology identifying ideal-typical possibilities based on Mann’s dimensions, centralization/autonomy and infrastructural development. Four combinations are possible, as follows: 1) The ideal Weberian state which is both autonomous, with adequate centralization of power, and has high infrastructural capacity (this ideal does not exist in its pure form in MENA). 2) A situation where the state has infrastructural capacity but is captured and deployed to benefit political elites at the expense of society—e.g. a predatory or kleptocratic regime; in this case, “capacity” would logically be restricted to one or two dimensions, with regimes prioritizing their security capacity (surveillance and coercion) and, to a degree, co-optative capacity; many of MENA’s post-populist republics appear to have features of this type. 3) The case where autonomy is high but capacity low; this seems to correspond to pre-modern states which are not expected to deliver many public goods except for law and order, and might fit a legitimate semi-constitutional monarchy in which the ruler is able to keep strong social forces—e.g. oligarchic elites—under control to prevent their predatory exploitation of the population. 4) The final type where autonomy and capacity are both low; the state is captured by and divided among several social forces thereby paralyzing it. In this configuration the state would also lack infrastructural power and in extreme cases would lose its monopoly on legitimate force over its territory to rival/opposition forms of governance—close to a failing state, as we see in several post-uprising MENA states, such as Syria (See table 1).

Even if we accept such a typology, we must remember that these are extreme ideal types, with actually-existing cases often located on the borders between the four “boxes.” Moreover, we have to think of graduated degrees of statehood as typical. At one end of the continuum lies Weberian statehood, and further towards the other end, predatory and premodern cases, and then at the extreme end, failing statehood. Somewhere between these extremes, and constituting the majority of MENA cases, would be weak states with some concentration of power but only limited decision-making autonomy and limited infrastructural power resulting in capacity deficits. Typically these states might have unbalanced capacity, e.g. they may be relatively strong on one dimension, such as “security” (control of opposition) and weak on others, such as delivery of services. A typical feature would be “hybrid statehood” (Bacik 2008) i.e. elements of rational-legal Weberian bureaucracy coexisting with traditional informal authority—or overlapping and even fusing with it, such as in neo-patrimonialism. In terms of infrastructural power, the result at the local level would be areas of limited statehood where power to implement policy is minimal.

At the extreme opposite end of the spectrum would be failing states with neither effective central authority or autonomy nor infrastructural power. It is the sudden increase in the numbers of states in this last category, as a result of the Arab uprisings, that has inspired the notion of the crisis of the MENA state. The notion of failing statehood does seem to apply to several MENA cases—notably Libya, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen—where, amidst civil war, regimes have lost territorial control to insurgents. This does not necessarily mean a total failure of governance since in “un-governed spaces” the state’s loss of its monopoly on violence over its territory opens the door to “rebel governance” (Arjona 2015). One way of conceptualizing the result is the notion of heterarchy, a scenario located between anarchy and hierarchy, denoting governance via competing authorities with different kinds of assets (military, economic etc.) and overlapping jurisdictions (Polese and Hanau Santini 2018). Governance of the same territory is shared between the withered state, non-state actors (rebel groups, NGOs, proxies of external powers), and external actors (intervening global and regional powers, international organizations).

Using the case of Syria to illustrate this scenario, the governance vacuum left by the retreat of the regime in the post-2011 uprising was initially filled by a variety of alternative forms of authority: local councils run by opposition activists, supported by external NGOs in some areas; “traditional” religious or tribal sheikhs; or by warlords and criminal cartels running the most primitives form of “governance”—protection rackets. These fragmented localistic forms of non-state governance were squeezed out over time by the regime’s recovery of control over much of western Syria on the one hand, and on the other, the rise of Salafist / jihadist forms of governance and a Kurdish-dominated proto-state in the north and east, each with its international patron.

The above realities should make it clear that variations in statehood do matter a lot for people’s lives. Given that, endeavours to understand and, where possible, measure these variations, are essential.

Bibliography

Arjona, Ana (2015) Rebel Governance in Civil War, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bacik, Gokhan (2008), Hybrid Sovereignty in the Arab Middle East: the cases of Kuwait, Jordan and Iraq , NY: Palgrave: Macmillan.

Huntington, S (1968) Political Order in Changing Societies, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kaldor, Mary (2005) “Old Wars, Cold Wars, New Wars and the War on Terror, International Politics, 42, pp. 491-08.

Mann, Michael (1984) “The autonomous power of the state: its origins, mechanisms and results,” European Journal of Sociology, 25, pp. 185-213.

Mann, Michael (2008) ‘Infrastructural Power Revisited,’ Comparative International Development, 43, pp. 355–365.

Mann, Michael (2014) “Infrastructural Power of Authoritarian States in the Arab Spring,” unpublished paper.

Newman, Edwin (2009), “Failed states and international order: constructing a post-Westphalian world,” Contemporary Security Policy 30:3, December 2009, pp. 421-43.

Polese Abel and Ruth Hanau Santini (2018) “Limited Statehood and its Security Implications on the Fragmentation Political Order in the Middle East and North Africa,” Small Wars and Insurgencies, 29:3, pp. 379-390.

Raymond Hinnebusch is professor of IR and Middle East politics and Director of the Centre for Syrian Studies at the University of St. Andrews. Recent publications include “Identity and State Formation in multi-sectarian societies: Between nationalism and sectarianism and the case of Syria,” Nations and Nationalism (2020); “The Rise and Fall of the Populist Social Contract in the Arab World,” World Development (2019); “Historical context of state formation in the Middle East: structure and agency,” in R.A. Hinnebusch & J.K. Gani (eds.) Routledge Handbook to the Middle East and North African State and States System (2020); “From Westphalian Failure to Heterarchic Governance in MENA: The Case of Syria,” Small Wars and Insurgencies (2018).

Cover image: Zes Circelvormige ontwerpen, Richard Nicolaüs Roland Holst (Dutch, 1868 - 1938). Image in the Public Domain.