Are Quotas a Solution for Equality?

18 May 2020

Marriage Migration: Female Paths

18 May 2020By Ghazala Azmat, Department of Economics*

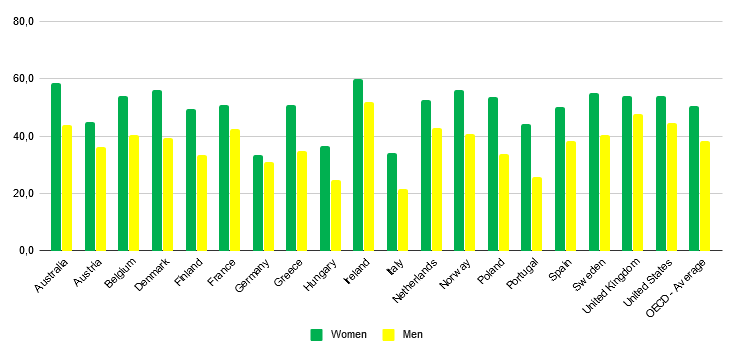

In most OECD countries, women have surpassed men in college completion. On average, more than 50 percent of young women have a college degree, compared with 38 percent of young men.

Proportion of women and men made college graduated in, 2018 in OECD countries

The rise in female educational attainment is not a recent phenomenon but one that has been noted over several decades. The removal of barriers for women into education and the labour market being important drivers of this increased investments in human capital. However, the changing patterns in higher education attainment have raised a number of new questions, baffling many social scientists.

The different values of a degree

Women’s under-representation at the top remains a mystery, especially given the numbers coming through. In the United States, for example, nearly a third of people who get an MBA are women; and the share of female law school graduates and female PhD holders is now almost 50%. Yet, even among high-skilled professionals, there remain big differences between men and women in their representation, earnings and career progression.

Among S&P 500 companies, women account for only 5% of CEOs and 26% of managers. In other professions, law and academia, underrepresentation is also common – for instance, women account for 20% of law firm partners and 32% of professors. Irrespective of position on the ladder, wage gaps between men and women for these highly skilled professional still persist.

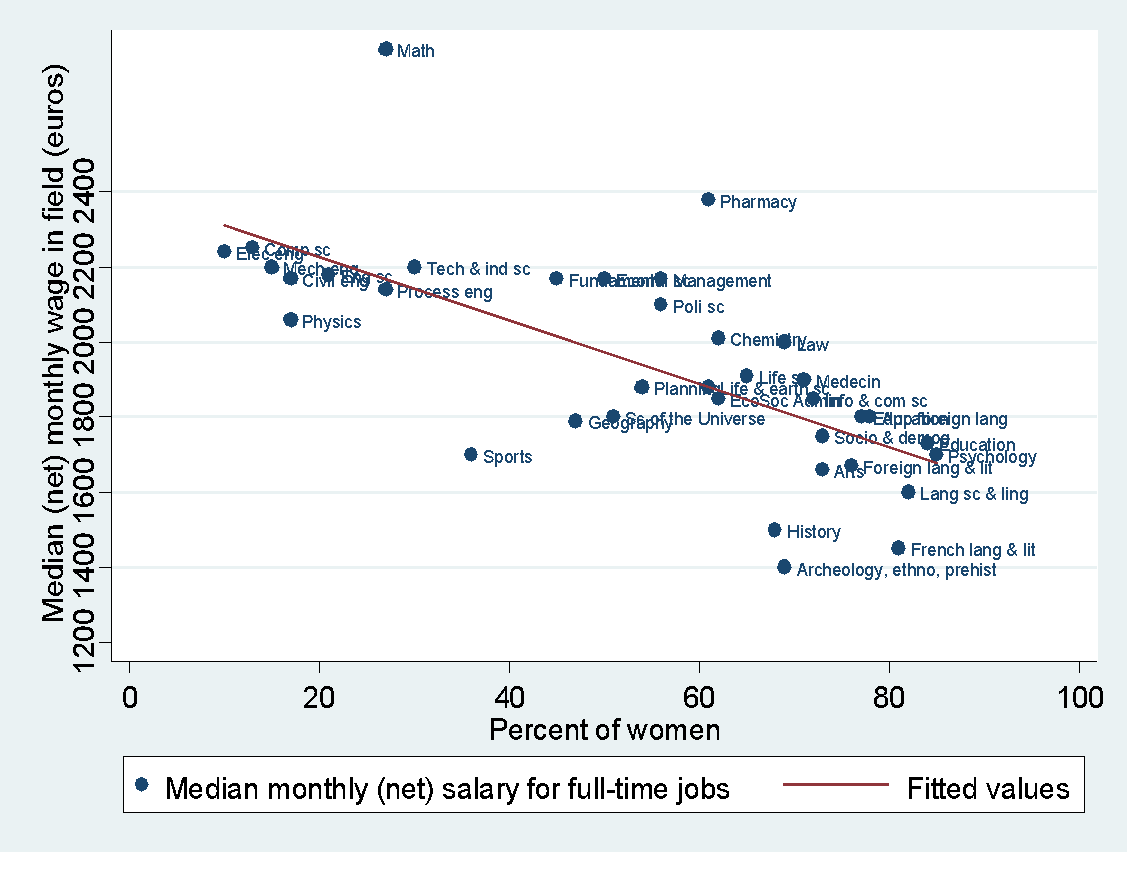

Where do gender inequalities among the college graduates stem from? An important first step is to look at differences in whether there are important differences in terms of what is studied at college and how this plays a role in later wage inequalities. The graph below plots, for France, the relationship between the average pay in each of the major fields of study and the proportion of women in those fields. With the exception of pharmacy, there is a clear negative relationship between average field wages and the proportion of women in those fields. Women are overrepresented in lower-paying fields, such as, arts, history, languages, psychology. Men, on the other hand, are overrepresented in highly paid disciplines, such as mathematics, computer science, and engineering.

Median (net) monthly salary en euros in France, 2016

Source: Insertion professionnelle des diplômés de Master en universités et établissements assimilés – données nationales par disciplines, Anne Boring (Le Monde, 2017) & Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation

A persistent wage disparities

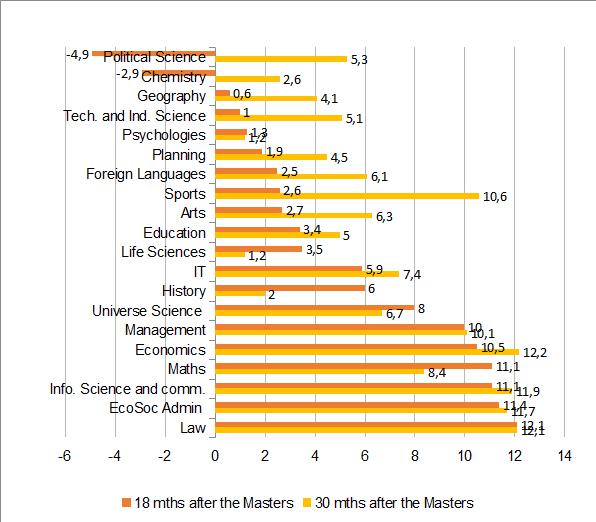

However, inequalities generated by field choice can only be part of the story. When looking at earning differences among men and women studying in the same field, we see that with no exception, women are paid less (Figure 3). Moreover, these gaps grow over time. Even in the relatively short term, comparing gaps in pay 18 months to 30 months after graduation, we see that, again, without exception across fields, the wage gap expands.

The evolution of the wage gap between women and men 3 months and 18 months after graduation in France, 2016

Source: Insertion professionnelle des diplômés de Master en universités et établissements assimilés – données nationales par disciplines, Anne Boring (Le Monde, 2017) & Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation

Wage disparities among similarly skilled college-graduated men and women is not the only puzzle surrounding the gender gaps in educational attainment. There is a growing interest to understand if men and women have different experiences in college. Taking a step back even further back, researchers are also asking why do school aged boys and girls make different decisions about going to college, and why do they make different choices about what to do if they decide to go.

Relative skill and behaviour differences

Sciences Po Libraty 2019© Caroline Maufroid / Sciences Po

There has been a recent interest in the role played by non-cognitive skills in explaining labour market and educational success. Differences by gender in behavioural and socio- emotional skills have been studied as a potential source to explain why less boys than girls go to college. The emphasis on good grades and academic performance, as well as conduct in the classroom, such as attendance, disciplinary incidents (arguing, fighting, disturbances), and social behaviour, often favour female students and have been shown to have a substantial impact on the probability of enrolling in college, even after taking into account cognitive ability and high school achievement(1)Jacob, B. “Where the Boys Aren’t: Non-Cognitive Skills, Returns to School and the Gender Gap in Higher Education” Economics of Education Review, 2002 ; Becker, Gary S., William H. J. Hubbard, and Kevin M. Murphy. “The Market for College Graduates and the Worldwide Boom in Higher Education of Women“ American Economic Review, 2010.

Gender differences in skills can also help us to understand why men and women choose different fields of study. While men are less likely to attend university than women, they are more likely to enrol in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields than women. Peter Arcidiacono researches of Duke University(2)Peter Arcidiacono, Duke University highlight the issue of gender differences in degree subjects that are traditionally predictive of high salaries later in life: ‘STEM majors, as with economics, begin with few women enrolling and end with even fewer graduating. This leaky pipeline has been somewhat puzzling, because women enter college just as prepared as men in math and science.’

OCDE (2015), The ABC of Gender Equality in Education : Aptitude, Behaviour, Confidence, PISA, Éditions OCDE, Paris

PISA comparisons (OECD, 2018) highlight that while gender differences in math skills are indeed small (average score of 492 for boys versus 487 for girls), while women have a large advantage in verbal skills (472 for boys versus 502 for girls).

An interesting recent study highlights that, in fact, verbal skills have a disproportionate influence on college enrolment, suggesting that gender differences in verbal skills are a key driver of the gender gap in college enrolment (3)Aucejo, Esteban M., and Jonathan James, “The Path to College Education: The Role of Math and Verbal Skills” Working Paper, 2019.. Moreover, the advantage that women have in verbal skills also has implications for the gender gap in STEM majors, since a comparative advantage in math influences the decision to major in STEM. Since women and men have similar distributions of math skills, the male disadvantage in verbal skills translates to a comparative advantage in math, leading to an increase in male representation in STEM.

The impact of a high pressure environment

Another dimension that could potentially explain gender differences for field choice, college experience, and then later, progressing in high-powered professions, is the pressure to perform and climb a ladder. It is commonly perceived that increasing incentives will improve performance. However, increased incentives often come with increased pressure. Taking final exams in school, undergoing the last round of a job interview, and going up for promotion, are some examples of situations with high stakes. Differences in the nature of tests—in particular, their objectiveness, their competitive nature and the skills they measure—have been used to identify the potential channels that explain gender gaps in performance and progress (4)Azmat Ghazala, Caterina Calsamiglia and Nagore Iriberri “Gender Difference in Response to Big Stakes” Journal of the European Economic Association, 2016.

To understand why only 29 percent of bachelor’s degrees in economics in the United States, Goldin (5)Goldin C. “Notes on Women and the Undergraduate Economics Major “, CSWEP Newsletter, 2013 showed that women who receive an A in an introductory economics were actually more likely than men with an A to major in economics. However, when women received poorer grade, they were less likely than men to choose economics as their major. Men who receive a B are as likely to major in economics as men with an A, while women with a B were twice as less likely to major in economics as women with an A.

© Zenzen, Shutterstock

One possible explanation for this puzzle is that some degrees (and some jobs) entail more pressure than others. Young people with a low tolerance for pressure will avoid degrees or firms that reward tolerance for pressure. It might also be that pressure in the selection process leads to candidates with low tolerance for pressure opting out.

To conclude, studying and understanding the decision to enter college entry, as well as choices made in college, are important first steps to understanding gender gaps in higher educations. These decisions, ultimately, having implications for the longer-run – potentially informing us on disparities in earnings and progression. While differential selection into university, fields of study, as well as differential responses to pressure, can help shed light on gender gaps among the high-skilled, from the perspective of policy, it is then important to target appropriately the disparities at the different stages.

Ghazala Azmat is a Full Professor at the Sciences Po Department of Economics. Her main research interests are in applied and empirical economics, with a particular focus on the economics of education, labour economics.

Notes

| ↑1 | Jacob, B. “Where the Boys Aren’t: Non-Cognitive Skills, Returns to School and the Gender Gap in Higher Education” Economics of Education Review, 2002 ; Becker, Gary S., William H. J. Hubbard, and Kevin M. Murphy. “The Market for College Graduates and the Worldwide Boom in Higher Education of Women“ American Economic Review, 2010 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Peter Arcidiacono, Duke University |

| ↑3 | Aucejo, Esteban M., and Jonathan James, “The Path to College Education: The Role of Math and Verbal Skills” Working Paper, 2019 |

| ↑4 | Azmat Ghazala, Caterina Calsamiglia and Nagore Iriberri “Gender Difference in Response to Big Stakes” Journal of the European Economic Association, 2016 |

| ↑5 | Goldin C. “Notes on Women and the Undergraduate Economics Major “, CSWEP Newsletter, 2013 |