Welfare and Reciprocity: Should We (Really) Feed the Surfers?

12 June 2022

Dying at Work? Industrial Society and the Relationship to Risk

13 June 2022 We know that the gender gap in the workplace widens when women become mothers, but some aspects of this inequality have been understudied, particularly the impact of parental leave. In a recent study on The motherhood penalty in Spain: The effect of full – and part-time parental leave on women’s earnings (Social Politics, 2021), Marta Dominguez-Folgueras and two colleagues measured and compared the impact of different types of parental leave in different countries. Their results show that the length of leave is a significant factor in deepening gender inequalities at work.

We know that the gender gap in the workplace widens when women become mothers, but some aspects of this inequality have been understudied, particularly the impact of parental leave. In a recent study on The motherhood penalty in Spain: The effect of full – and part-time parental leave on women’s earnings (Social Politics, 2021), Marta Dominguez-Folgueras and two colleagues measured and compared the impact of different types of parental leave in different countries. Their results show that the length of leave is a significant factor in deepening gender inequalities at work.

The glass ceiling is often seized as a signpost of gender inequality in the labour market, as numerous indicators reveal. Whether defined in terms of pay or status, the facts are clear: women hold less prestigious jobs, more often on fixed-term contracts, and have less linear careers(1)Report on the Implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations – Some Progress on Gender Equality but Much Left to Do, OECD 2017.. The most infamous indicator of this imbalance is probably the gender pay gap: 13% in Europe in 2020, and 15.8% in France, according to Eurostat(2)Écart des rémunérations entre hommes et femmes (non corrigé), Eurostat..

This gap is observed in all the countries for which we have data, and numerous studies have sought to analyse it. Findings show that the gap is linked to differences in training and professions (women are overrepresented in less well-paid sectors), to discrimination (some employers prefer to hire men for supervisory positions, for example), and to divergences in career paths, which are less linear for women, because they more often interrupt their professional activity in order to take care of their family.

Motherhood thus widens the pay gap between women and men, to the point where it is referred to as a ‘motherhood penalty’. Welfare states have developed various policies to protect women’s employment and their earnings, while helping them balance paid work and family life. These so-called family policies are always linked to the labour market.

A Variety of Social Policies

A particularly dynamic public policymaking area, family policies have been constantly evolving in recent years(3)Ferragina, Emanuele. 2017. Does family policy influence women’s employment ? Reviewing the evidence in the field, Political Studies Review., as evidenced by ongoing debates on paternity leave in a series of countries. Their main objective is to support parents – especially mothers – by implementing benefits, creating public services (daycare centres), and granting time (parental leave). While each of these policies can have a positive impact on parents’ paid employment, the focus here is on parental leave.

Several types of leave exist, and in our study (Dominguez Folgueras, Marta, Maria José González et Irene Lapuerta. 2021. The motherhood penalty in Spain: The effect of full—and part-time parental leave on women’s earnings. Social Politics, online first.), we identified very different configurations across countries (the Leave Network of researchers publishes a detailed description by country every year). The literature broadly distinguishes three types of leave related to parenthood. Maternity leave, reserved for mothers before and after the birth, aims to protect their health and ensure they can return to work. Paternity leave is generally shorter and conditions for taking it are more flexible. Both types of leave are usually paid at an amount close to the level of pay that preceded them. Parental leave comes after these first types of leave and is designed to allow parents to leave their jobs for a certain period of time while ensuring that they will be able to return to the jobs they left. These leaves are generally longer and allow for the care of young children, but are usually poorly paid if at all. In countries where leave is available to all parents, women mostly take parental leave (Leave Network).

Parental leave protects mothers’ employment and labour market attachment, but it can also have unintended consequences. Research has shown that long leaves negatively impact women’s earnings, although the optimal length of leave varies by country(4)Grimshaw, Damian, et Jill Rubery. 2015. The motherhood pay gap : A review of issues, theory, and international evidence. Conditions of Work and Employment Series.. How to explain this penalty? Two mechanisms shed light on the phenomenon. First, the absence resulting from the leave leads to a loss of human capital, making it harder to obtain promotions or salary increases. Second, people who take parental leave could be stigmatised within the company because the interruption might be perceived as a sign of low commitment.

Effects Vary Depending on the Type of Leave

While the length of the leave and its negative impact on remuneration has been widely studied, other dimensions remain underexplored. For instance, in a number of countries (e.g. Germany, France, Spain), parental leave can be taken on a full-time or part-time basis. This feature could be very important, as full-time leave could entail a greater loss of human capital (knowledge and experience), and could be perceived as a lesser commitment to the job than part-time leave, which would help maintain a link to the job and minimise the experience loss from the absence. Is this really the case?

Only one study – on France – has addressed this question(5) Joseph, Olivier, Ariane Paihlé, Isabelle Recoltillet, et Anne Solaz. 2013. The economic impact of taking short parental leave : Evaluation of a French reform. Labour Economics.. Comparing the effects of part-time versus full-time short parental leaves (up to six months), it found that full-time leave had no impact on mothers’ wages, whereas part-time leave had a negative effect. While these results seem to refute the hypothesis put forward earlier, they can be explained by the features of the leave and the option of reduced working hours for parents of young children – a practice that is fairly widespread in France. The short length of the analysed leave may explain why it does not result in a penalty. Moreover, it is possible that women who choose part-time leave then remain on that schedule when they return; hence the impact on their earnings. This part-time parental leave could therefore help facilitate a transition to part-time work for parents, especially mothers, who take it much more often.

Part-Time Leave in Spain

In Spain, parental leave is unpaid; when taken on a full-time basis, it allows parents to leave their jobs for three years and return to a guaranteed job at the same company. If the leave is less than one year, the person can return to his or her previous job. If the leave is longer, the company must offer a ‘similar’ job (as designated by the law without being specified). If parental leave is taken on a part-time basis, the parent negotiates with the employer for a period ranging from one hour per day up to half a day, in an arrangement that can be extended until the child turns 8.

We wanted to know whether this option would penalise mothers in the same way as full-time leave. Our initial hypothesis was that full-time leave would be more penalising for mothers, as it is associated with a greater loss of capital, and a total absence could be more stigmatising.

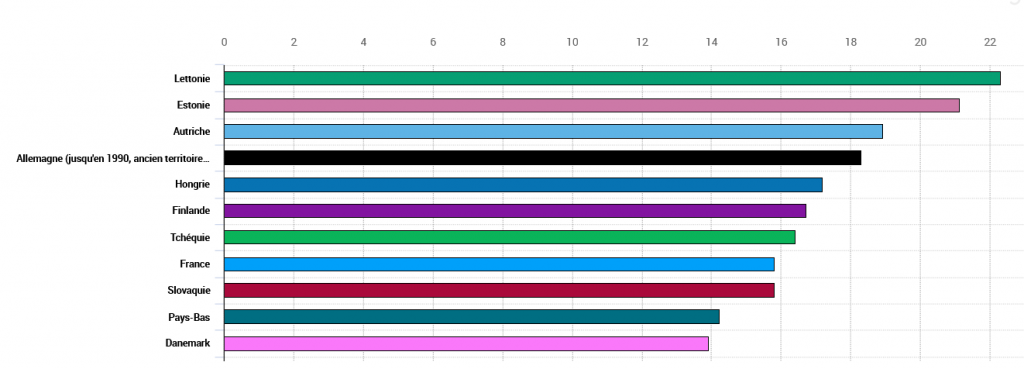

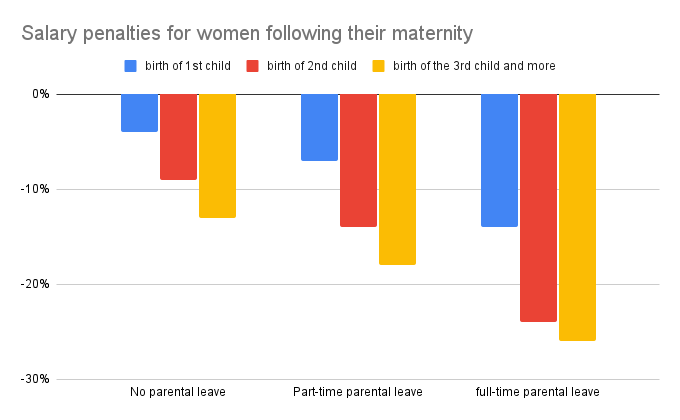

To analyse the impacts of both part-time and full-time leaves on women’s pay, we used data from a Spanish survey over extended periods of time (Muestra Continua de Vidas Laborales). On this basis, they were able to observe changes in the earnings of women between the ages of 25 and 40 from 2005 and 2012, test the size of the motherhood penalty, and determine the consequences of taking various forms of leave. Our results show that the motherhood penalty does exist, as the graph below shows.

The penalty for full-time leave is therefore much greater, but in calculating the total loss, part-time leave – which is often of longer duration – may be more penalised than full-time leave.

Both leaves protect women by allowing them to return to their jobs, but the leaves impact their earnings and most likely their career development. Research must take into account the ways in which leave is taken in order to better understand how wages evolve in relation to motherhood, and differences between men and women. These are all elements that could help inform the development of more egalitarian public policies.

Marta-Dominguez Folgueras, Observatoire de sociologique du Changement (OSC)

Marta-Dominguez Folgueras is Associate Professor in sociology at the Observatory for Social Change (OSC). She focuses on the sociology of the family, the sociology of time use, and the sociology of gender. Her current research examines couple formation and family behaviour, and particularly gender inequalities involved in the division of domestic tasks and childcare.

Notes

| ↑1 | Report on the Implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations – Some Progress on Gender Equality but Much Left to Do, OECD 2017. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Écart des rémunérations entre hommes et femmes (non corrigé), Eurostat. |

| ↑3 | Ferragina, Emanuele. 2017. Does family policy influence women’s employment ? Reviewing the evidence in the field, Political Studies Review. |

| ↑4 | Grimshaw, Damian, et Jill Rubery. 2015. The motherhood pay gap : A review of issues, theory, and international evidence. Conditions of Work and Employment Series. |

| ↑5 | Joseph, Olivier, Ariane Paihlé, Isabelle Recoltillet, et Anne Solaz. 2013. The economic impact of taking short parental leave : Evaluation of a French reform. Labour Economics. |