Are Elected Officials Compensated for Working?

13 June 2022

How Work Became a Revolutionary Concept

13 June 2022

Office National des Forêts, the Minister of Agriculture marking a tree to be used in renovating the frame of Notre Dame de Paris, March 5, 2021, Bercé forest, Facebook-ONF

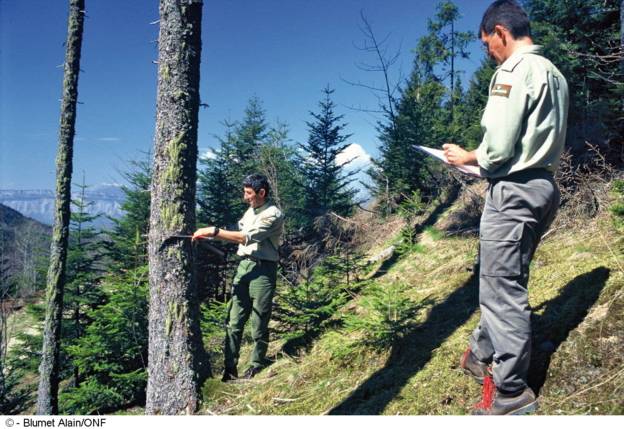

In March 2021, the National Forestry Office (ONF) shared on social media a photograph of the Minister of Agriculture marking a multi-hundred-year-old oak tree intended for the renovation of the frame of Notre-Dame de Paris. Marking, which forest rangers(1)This is the name most commonly used by the general public. They are called Territorial Forestry Technicians (TFT) internally. carry out in public forests consists of designating the trees to be cut or protected via a hammer mark. It represents both the State’s hold(2)The public institution is responsible for the management of public, communal, and state-owned forests, which cover 4.3 million hectares, i.e. a quarter of the forests in metropolitan France. IGN, Le memento. Inventaire forestier, 2021. on the territory and a core symbol of the forestry profession. However, marking is changing: forest rangers, like their engineering and blue-collar colleagues, must overhaul their work techniques in light of global warming challenges and their decreasing workforce.

At the heart of a study(3)Conducted as part of my doctoral dissertation on “Forests in the fight against global warming. Sociology of work and forest governance.”that took me to European, national, and regional administrations, as well as the cabins of mechanical harvesters, I will focus here on the work of forest rangers through marking. Indeed, this technical act is an ideal lens for understanding the State’s action on forests in a context of climatic uncertainty insofar as it constitutes a key decision-making moment in forest management. The study of work as an activity at the forest ranger level(4)Bidet Alexandra, et al. (ed.), Sociologie du travail et activité, Octarès, 2006; Kaufman Herbert, The forest ranger. A study in administrative behavior, John Hopkins University Press, 1960.allows for a better understanding of the materiality of public forestry action and the debates it involves.

Tree Marking: the State’s Imprint on its Forests

Carried out on average twice a week in regions with a forestry tradition such as the Vosges, it consists of designating the trees to be cut down (abandonment marking) and more rarely kept (reserve marking). The harvested trees allow other trees to grow; the retained trees, be they alive or dead, are valued for biodiversity (bird and insect habitats, etc.). Marking is a collective activity that brings together all the members of a territorial unit who go out in a line and sweep the plots one after the other. The forest rangers follow the marking instructions given by their colleague in charge of the plot, according to the management document produced by the ONF’s territorial agency, which in turn must follow regional management directives and schemes, and national guidelines.

Once a decision has been made on the fate of each assessed tree, it is marked using a forestry hammer, consisting of a hatchet on one side and a seal inscribed in Gothic letters ‘AF’ (for ‘Forestry Administration’) on the other. The marking is done in three stages. First, the guard removes a piece of bark with the edge of the hammer in a vertical movement (the flachis), then affixes the State’s seal at chest level so that it will be visible to colleagues and then to the loggers. Next, he repeats the operation at the foot of the tree, ‘at the collar’. This second sign allows the guard to do the ‘récollement’ afterwards, i.e. to control the cut, as the woodcutter must cut the tree above this mark. The guard can ensure that only the marked trees, chosen by his peers, were cut. If he notices unmarked stumps, he can fine the logging company. Thus, the marking embodies both the authority of the State (through the choice and control of operations) and the autonomy of field workers. The latter is based on their discretionary power over the trees and the independence of their forestry judgment, which is protected by the anonymity of the seal – that of the state. Decisions are made ‘for the sake of the forest’: the volumes of wood to be marked per hectare are proposed by a public, independent planner, and not by wood buyers. Therefore, marking is an act of the affirmation of the forest rangers’ expertise, as one of the foresters I met put it: marking ‘to the best of their knowledge and belief’ in the service of the State.

Marking: A Complex Expertise in the Face of Global Warming

Marking sequence, Vosges forest, March 2021. Crédit : Charlotte Glinel.

However, with global warming and biotic (insect parasites, fungi, etc.) and abiotic (droughts, fires, pollution, etc.) threats’(5)For example, in the fall of 2020, the industry decried the 7,000 hectares that went up in smoke in Mediterranean forests, 30,000 hectares of spruce forests decimated by bark beetles – parasitic insects in the Great East whose demographic expansion is exacerbated by global warming..buffeting forests, it has become harder to mark ‘in all good conscience’. Indeed, the emergence of climate change over the past twenty years has shadowed the development and confrontation of technical expertise on ‘good management’ of forests.

In France in particular, the debates pit supporters of a rationalised and centralised management promoting the renewal of forests by plantation, against supporters of an continuous cover forestry supported by the public foresters’ unions calling for the natural regeneration of stands, for more staff in the field, and for the rejection of industrial ‘malforestation’. These debates lead forestry professionals to question their own forms of expertise, and to confront, redefine, sometimes assert them in a continual process of negotiating their identity. In the field, when it comes to deciding on the material fate of trees, uncertainty reigns, as reflected in the experience of a retired forest ranger we met: ’What we learned at school, what we were told before, with climate change, as they say, well, it doesn’t work well. (…) Should we keep a dense forest cover, cut more to renew more? The scientists don’t agree, and we have to do our own thing when we’re in the field’.

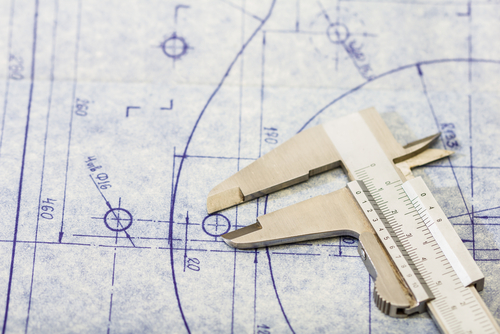

Marking is primarily the exercise of a sharp eye (6)Guidoni-Stoltz Dominique, « L’œil du forestier, instrument et miroir de l’activité professionnelle », Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances, 2020. requiring that the professional relates many variables: interpretation of the work of predecessors, botanical, geological, and forestry knowledge… To do this, the forest ranger must look at the ground, the surroundings, and then the tree crown(7)“All the branches of a tree and the upper part of a trunk (i.e., trunk excluding bole),” Glossaire des communes forestières du Grand Est, 2020. and estimate the state of the leaves or needles, as well as the height of the tree, “according to expert opinion”. “What happens if I cut down this tree next to it? Will it bring in light? Will it deteriorate the forest atmosphere by drying out the soil?” These were the questions of a ranger who explained to me during a tour that he keeps the beech trees to “shade the small firs”. The forest is thus perceived as a network. If a tree catches the ranger eye for cutting, he measures its diameter with a forestry compass. His decision to mark it or not is then made while bearing in mind the “climatic emergency”, which results in significant and unexpected die-offs, and doubts about the right approach. To answer these questions, the ranger must combine the instructions he has received for marking (to follow a regular or continuous cover forestry practice, to favour such and such a species, to designate a certain total volume of trees), with external knowledge. The latter comes from his observations of similar plots of land, from forestry recommendations made by the forestry department, and from theoretical training. In a few seconds, he anticipates the fate of a piece of forest in a warmer climate.

Eyes turned toward the tree crown, evaluation of a fir tree, March 2021. Credit:Charlotte Glinel

Marking: an Expression of the Need for a Presence in the Field

This knowledge especially develops during marking days which, like most “field days” (plot inventories, naturalist descriptions, trainings), are moments of conviviality and professional knowledge sharing. The forest rangers, sometimes accompanied by engineering superiors or specialists, discuss and compare abstract knowledge with concrete cases. Beyond discussions about the fate of particular trees, each professional’s individual forestry sensitivities are apparent during the trip. Once the tree is designated, the ranger shouts to the pointer, who notes and synthesises the set of marked trees, its species and its diameter, so that the information is also audible to his colleagues. By listening to each other, a balance emerges on the marking sheet, as one team leader (territorial unit manager) explained to me, “Some mark more, and some less … and that’s what makes for a diverse forest!”

Forest rangers regularly say that marking is “the heart of the job”, with their professional identity nourished by an intrinsic link to the territory they manage. Each one manages a group of forest parcels called a “triage” within a territorial unit. They know the history of the area and carry out a range of activities with relative autonomy, due to the nature of their work, which is difficult to standardise. In order to carry out their missions, the rangers underscore the importance of their presence in the field, bolstering their claimed experiential expertise. However, contact with the managed plots of land is becoming increasingly rare as jobs have been cut while the areas to manage have increased. Since the 2000s, ONF workers have been facing successive managerial reforms that have led to the elimination of nearly one third of the workforce. The most affected are the administrative and field staff, including forest rangers. If the latter are so present in the public debate, it is as much the result of fascination for their profession(8)We can refer to the many radio stations that follow forest rangers (such as France Culture, “Antoine, forest ranger”, L’heure du documentaire, 14 August 2017; France Inter, “Alexis Hachette, forest ranger”, Une semaine dans leurs vies, August 2021 as of the necessity of their expertise for sustainable forest management and public policy implementation. Their expertise has been recognised over the past thirty years by their superiors – forest engineers who no longer participate in marking operations(9)This was the case until the 1980s, as a legacy of the Eaux et Forêts department. and by other public actors shaping public policies. Thus, in March 2022, at the closing of the Forest and Timber Conferences convened by the Ministries of Agriculture and Ecological Transition, a researcher from the National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and the Environment (INRAE) emphasised the need for “people in the field who are able to be as close as possible to where it is done in order to guide public and private landowners in ambitious adaptation strategies. These people must be recruited and trained.” It thus appears that the current forestry controversy is not just about land use planning, but primarily about forms of forestry work given an uncertain climatic future whose contours and transformations must be studied.

The challenges that global warming raises for public forestry action are not just a discursive reality. They are also embodied in the individual and collective destiny of trees and forests, depending on the decisions forestry professionals make in the field, reflecting one vision or another of the forest. The decisions are based on forestry socialisation developed during their training and career. This brief sketch(10)Today, in spite of internal debates, tree-marking is increasingly done with paint, and the marking sheet is replaced by digital input terminals. These changes are analysed in an article that is currently being finalised. of markings in public forests shows how debates on adapting forests to global warming are fully integrated in the activities of the professionals in charge of the forest’s management: in the decisions taken at the foot of each tree, in the sharing of knowledge and uncertainties, and in the conditions of its realisation. To consider the materiality of the work and its instruments, and the embodiment of public action, is to enable understanding of how the climate crisis is also a professional crisis in French forests. The uncertainties that the climatic situation brings to bear on management choices are all the more intense within the ONF as its professionals face constant task readjustments. The tension is exacerbated by the fact that the expertise produced by the institution, from the research and development department to support programs for rural municipalities, remains indispensable and expected by their state, municipal, and private partners.

Charlotte Glinel, Centre for the Sociology of Organisations

Charlotte Glinel is a PhD student at the CSO, where she is working on a sociology thesis regarding “Forests in the fight against global warming. Sociology of work and forest governance” under the supervision of Sylvain Brunier and Jean-Noël Jouzel. She has just published an article with Aliénor Balaudé and Julie Madon in Socio-Anthropologie entitled “Three sociologists in an armchair. How forced digitalization impacts research conditions and collected materials.”

Notes

| ↑1 | This is the name most commonly used by the general public. They are called Territorial Forestry Technicians (TFT) internally. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The public institution is responsible for the management of public, communal, and state-owned forests, which cover 4.3 million hectares, i.e. a quarter of the forests in metropolitan France. IGN, Le memento. Inventaire forestier, 2021. |

| ↑3 | Conducted as part of my doctoral dissertation on “Forests in the fight against global warming. Sociology of work and forest governance.” |

| ↑4 | Bidet Alexandra, et al. (ed.), Sociologie du travail et activité, Octarès, 2006; Kaufman Herbert, The forest ranger. A study in administrative behavior, John Hopkins University Press, 1960. |

| ↑5 | For example, in the fall of 2020, the industry decried the 7,000 hectares that went up in smoke in Mediterranean forests, 30,000 hectares of spruce forests decimated by bark beetles – parasitic insects in the Great East whose demographic expansion is exacerbated by global warming.. |

| ↑6 | Guidoni-Stoltz Dominique, « L’œil du forestier, instrument et miroir de l’activité professionnelle », Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances, 2020. |

| ↑7 | “All the branches of a tree and the upper part of a trunk (i.e., trunk excluding bole),” Glossaire des communes forestières du Grand Est, 2020. |

| ↑8 | We can refer to the many radio stations that follow forest rangers (such as France Culture, “Antoine, forest ranger”, L’heure du documentaire, 14 August 2017; France Inter, “Alexis Hachette, forest ranger”, Une semaine dans leurs vies, August 2021 |

| ↑9 | This was the case until the 1980s, as a legacy of the Eaux et Forêts department. |

| ↑10 | Today, in spite of internal debates, tree-marking is increasingly done with paint, and the marking sheet is replaced by digital input terminals. These changes are analysed in an article that is currently being finalised. |