Divided cities: between fragmentation and integration

12 October 2017

Karachi: Ordered Disorder

12 October 2017Sukriti Issar, a young Indian sociologist of Sciences Po’s Sociological Observatory of Change, focuses her research on urban policy in India, and especially unplanned urbanization phenomena in Mumbai. While her research goes back to the end of the 19th century, she takes an applied research approach that involves direct contact with actors on the ground. Here is an overview of her research.

The journey to from market to home for a resident of the Dharavi slum by Meena Kadri. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The growing share of informal housing

I

in major global cities, informal housing represents a significant share of the urban space. In the coming years, 90% of urban growth will be concentrated in Asia and Africa and millions of residents will choose precarious housing that is not regulated by local authorities (United Nations, 2014).

The UN defines informal housing by degraded construction standards (no access to drinking water or toilets, unsustainable construction materials) and nonexistent or unclear property rights.

From informal housing to “slums”

Slum in Mumbai. Crédits Sukriti Issar, 2009

Informal housing is designated by different names across the world, but the English term “slum” is the most widespread. While many public actors, activists and researchers advise against using this charged and demeaning term, it is precisely its use in Mumbai as a political subject over the past 150 years that is of interest to Sukriti Issar.

Her research proceeded in two stages: first, she examined the archives and interviewed urbanists, officials and residents to trace the evolution of the urban sprawl, to compile local urban rules, to observe the debates to which they have given rise, and to assess their implementation on the ground. The idea was to explain how uncontrolled urbanization gradually entered the legal field – under the term Slum – to become a legitimate area of public intervention. Second, she used these materials to advance urban theories.

Slums as a legal and political subject

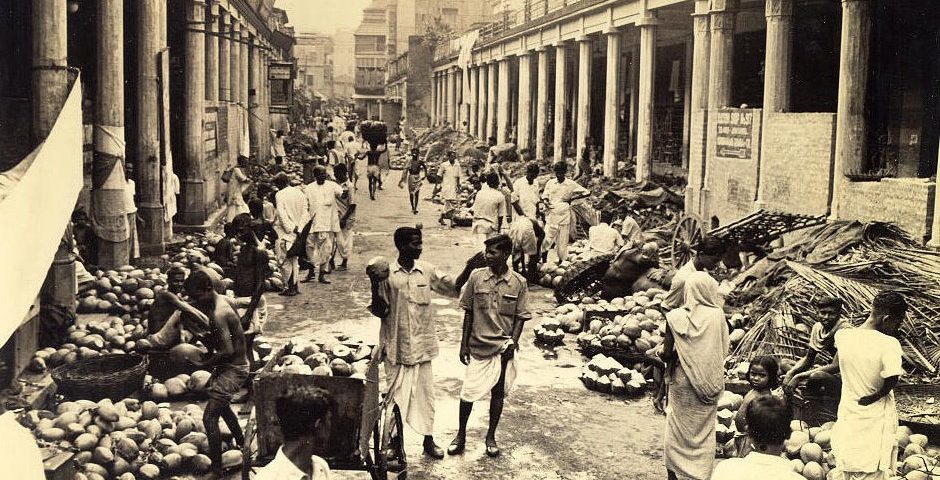

![This cocoanut market on Cornwallis Calcutta in 1945 By Clyde Waddell [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons This cocoanut market on Cornwallis Calcutta in 1945 By Clyde Waddell [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Coconut_market_on_Cornwallis_Street_Calcutta_in_1945-300x231.jpg)

This cocoanut market on Cornwallis Calcutta in 1945 by Clyde Waddell [Public domain]

From the 1940s to the 1960s, as the population rapidly grew under the influence of postwar migrations and of the consequences of the partition between India and Pakistan, the definition evolved and came to emphasize the absence of legal property rights. These constructions were frequently called Slums, “unauthorized constructions”, “encroachments” and “squats” (illegal occupations). At the end of the 1960s, local authorities destroyed certain places of this type but simultaneously enacted protective measures for their residents. Efforts were made to build collective infrastructure, while nongovernmental organizations and activists defended the residents concerned. The issue of their rights emerged little by little.

A complicated story

Many researchers question the modern rules of urbanism inspired by neoliberalism; Sukriti Issar’s research shows that informal housing has represented a persistent political problem despite successive policy changes, legal regulations and actors. Through a detailed analysis of public policies and their long-term timetable for implementation, she shows that regulations and informal housing have always coexisted and evolved together: they are historically interdependent.

(2017), Codes of Contention: Building Regulations in Colonial Bombay, 1870-1912. Journal of Historical Sociology, 30: 164–188.

Previous post: Divided cities: between fragmentation and integration <-> Next post: International migrations: metropolises, places of inclusion or drivers of exclusion?