Ambulatory Medical Care in France

12 December 2021

Measuring the Quality of Care, a European Overview

12 December 2021The Students’ Perspectives

By Agnès van Zanten, Alice Olivier, Christophe Birolini, Audrey Chamboredon et Léon Marbach

‘Saying it is no longer a competitive exam, this is what the university is trying to do, but, in fact, nothing has changed. […] We are still evaluated in the same way, we have almost the same subjects, almost the same examination arrangements, so, what has changed for me is just the name. It is nothing more than illusions given to the students…’ (Florian, PASS student)

This quote, taken from an interview with a student from the French university where we have been conducting a study since August 2020 on the enactment and reception of a national reform of access to health studies(1)The research presented in this article corresponds to the second axis of a research project on the French reform of access to health studies, coordinated by Agnès van Zanten, and was conducted by Alice Olivier (co-coordinator of the axis with A. van Zanten), Christophe Birolini, Audrey Chamboredon and Léon Marbach. The research includes a two-part survey sent to a sample of first-year students (N= 879 for part 1, December 2020; N= 635 for part 2, March 2021) and two series of interviews with around forty students. This project is supported by a public grant overseen by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the “Investissement d’Avenir” program. is a good illustration of two aspects of students’ perceptions of this reform. Firstly, their primary concern, above all other aspects of the reform, is about the selection process. Secondly, except for the most politicised among them, their positions are more pragmatic than ideological: their views change as the students discover how the reform is effectively enacted and its implications on their chances of being admitted into health studies.

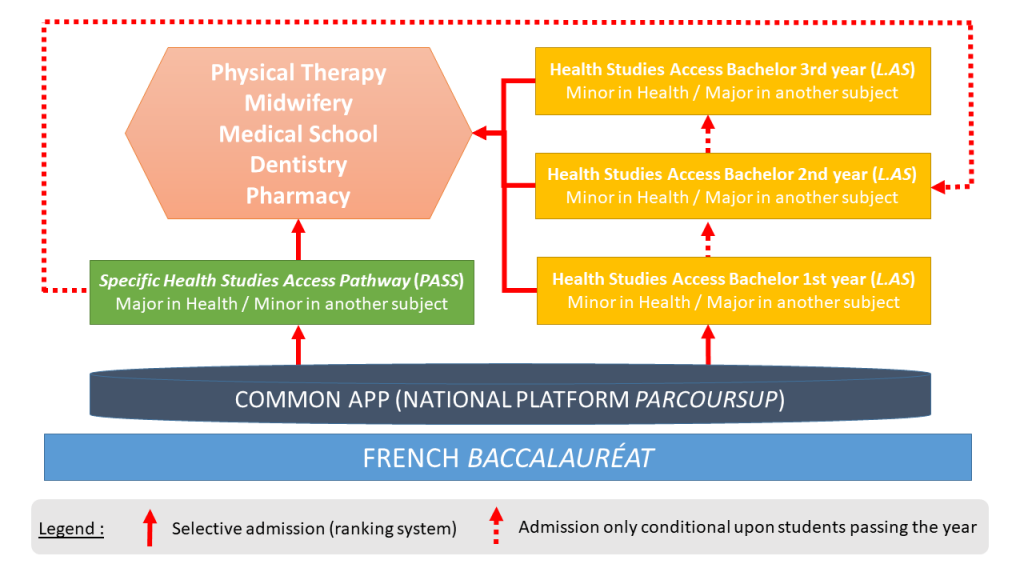

This reform, which is part of the 24th of July 2019’s law on the organisation and transformation of the French healthcare system, changes the conditions of admission into the different health tracks (medical school, midwifery, dentistry, pharmacy and, in some universities, physical therapy). It creates two access routes: the PASS (Specific Health Studies Access Pathway) and the L.AS (Health Studies Access Bachelor), which operate on a major-minor system to encourage the integration of non-health related subjects and facilitate reorientations to other academic tracks. The PASS offers a health major and a minor in another field; the L.AS is a traditional bachelor degree combined with a minor in health. The reform enables students to validate European credits (ECTS) through final exams – which officially replace the ‘competitive exams’ or concours of the pre-reform PACES track into health studies – introduces oral exams and replaces the numerus clausus, in place since 1971, by a numerus apertus. This latter transformation means that universities now determine the enrollment capacity in each of the health studies track, according to the needs in healthcare professionals in the territory in which they are located.

Organisation diagram of the new PASS and L.AS tracks following the reform of health studies in 2020

Perspectives Embedded in Contexts, Roles and Pathways

Perspectives Embedded in Contexts, Roles and Pathways

It would be easy to view the students’ attitudes towards this reform, and to reforms in general, as individualistic and ‘short-termist’. This contributes to the fact that political leaders, as well as researchers, generally pay little attention to students’ role in the reception of reforms(2)Revillard A., 2018, « Saisir les conséquences d’une politique à partir de ses ressortissants : la réception de l’action publique » – Understanding the consequences of a policy based on its nationals: the reception of public action – Revue française de science politique, except when students participate in demonstrations against them. However, this attitude becomes understandable if we consider it in the context of the French education system as a whole, which is oriented towards the selection of the best students, promoting the intrinsically fair nature of merit-based competition(3)van Zanten A., 2018 – « La fabrication familiale et scolaire des élites et les voies de mobilité ascendante en France » – “How families and schools produce an elite. Paths of upward mobility in France – in A. van Zanten (ed.) Elites in Education, Londres, Routledge, coll. Major themes in education, 2018. These features lead many young people, from high school, to adopt utilitarian practices vis-à-vis the selection tests and to be sensitive to the injustices arising from the nature of these tests, their enactement or the calculation of the results.(4)Dubet F. Les lycéens, Paris Seuil ; Dubet F., 2004, L’école des chances, Paris, Seuil..

Medical School © Amine GHRABI via Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

In such a system, any reform that alters the selection procedures generates both hopes and concerns because of the high degree of abstraction and the multitude of objectives announced. Furthermore, there is a sizeable gap between the initial intentions and the actual policies because of the autonomy of the institutions responsible for their enactment(5)van Zanten A. 2021, Les Politiques d’éducation (4e ed.), Paris, PUF.. This is particularly salient in the case of the reform considered herein, which was described as having a ‘very complex architecture’ and as having been implemented with a ‘lack of anticipation and framing’ in a severe report from the French Parliament(6)“Mise en œuvre de la réforme de l’accès aux études de santé : un départ chaotique au détriment de la réussite des étudiants (Implementation of the reform of access to health studies: a chaotic start detrimental to students’ success), Information report no. 585 (2020-2021) by Ms. Sonia de la Provôté, written on behalf of the culture, education and communication commission, registered 12 May 2021.. Thus, the exact outlines of this reform, variable from one university to another, are only defined gradually, notably those concerning the exact nature of the exams and the enrollment capacities in the different health tracks.

Howard Becker, Blanche Geer and Everett Hughes’ research(7)Becker H., Geer B., Hughes EC. et Strauss A.L., 2003 (1961), Boys in White. Student Culture in Medical School, New Brunswick, Transaction Publishers. helps us understand the positions of students faced with reforms in higher education, such as the one we are studying. Firstly, like the students in Kansas in the 1960s, it is logical that French students today should be focused on grades and their consequences, because the selection process determines their survival within the institution and their subsequent professional careers. Like their American counterparts, their passive attitude towards grading and selection is also due to the fact that they are put in a position of subservience, not being consulted, or only rarely, on teaching content and pedagogy or on how they are evaluated during their studies.

The concept of ‘perspective’ elaborated by these authors in their research on medical students (8)Becker H., Geer B.et Hughes E.C., 1995, Making the Grade. The Academic Side of College Life, New York, Routledge. which includes viewpoints and practices, is also relevant to our case. Perspectives emerge in response to situations perceived as problematic, like those generated by organisational and political changes. This concept highlights the fact that students’ viewpoints and actions are influenced by their position in the organisation and the effects they anticipate, more than by previously acquired dispositions and resources, although more subtle differences are observed between students depending on their gender and social origins.

Perspectives Influenced by the Degree of Information, the Pathway to Health Studies and the Experience of the First Year

At the start of the academic year 2020-21, the PASS and L.AS students we interviewed often had no clear opinion about the reform. However, even if their views were mostly positive on certain aspects – ‘Having a minor means you can bounce back very easily’ (Florian, LAS); ‘It offers […] an opportunity for people who […] did not prepare a scientific baccalaureate to get into medical school’ (Alix, PASS) – differences related to their degree of information were already apparent. Some, who were very informed beforehand about the new conditions of training and selection, felt comfortable with the workings of the first year overall: ‘we even have too much information […], every open day, […] every careers fair, there was at least one conference on […] medical studies, the reform, etc.’ (Loïc, LAS). Others, less informed, were more worried: ‘I think some points still have to be clarified, to reassure the students in any case […]. I mean, I would like to be reassured’ (Anaëlle, LAS). The variable level of support available to students in terms of guidance for higher education choices depending on the type of high school attended (public or private schools, privileged or not), and socially differentiated family approaches to guiding study choices, likely play an important role here(9)Olivier A., Oller A.C., van Zanten A., 2018, «Channelling students into higher education in French secondary schools and the re-production of educational inequalities. Discourses and devices», Etnografia e Ricerca Qualitativa..

Their chances of being accepted into the different health tracks and the lack of clarity over selection criteria already crystallised students’ concerns and criticisms, but to varying degrees, depending on the selected pathway and on their previous education. Those starting their studies in L.AS see the creation of a new access route as a real opportunity: ‘The word PACES was actually scary in itself. […] [The L.AS], I think it opened a door for me’ (Malia, L.AS). The L.AS students who had already undergone a PACES year before were less enthusiastic, seeing the L.AS as a detour that meant they lost a year before being able to start their health studies.

Reservations about the reform, notably about the selection process, were more pronounced among PASS students. Some saw the absence of students repeating a year in their year as a ‘big advantage’ (Adel, PASS) because of the reduced competition, but this was not enough to alleviate their fears over workload, which they saw as having increased due to the addition of a minor. Above all, they expressed concern from the start of the year, about their chances of being accepted into a health track, condemning the ‘hypocrisy’ of the official stance that the competitive exam no longer existed in spite of the high level of selectivity that remained: ‘A classifying exam or a competitive exam, there is no difference’ (Anna, PASS).

The experience of the first year further reinforced these negative perspectives. The answers to the second survey sent out to PASS students in March 2021 (six months after the start of the academic year and three months after the first survey), show that their opinions about the reform, which were already largely critical in December 2020, had become even more negative. Indeed, 66% of them declared that the reform does not create more opportunities to access medical studies than the former PACES system (+10 points compared with December 2020), 65% that it does not train more ‘human’ doctors (+18 points), and 71% that it does not offer a clearer perspective on health studies (this question was not part of the December 2020 survey).

Changing Perspectives According to the Effects of Experienced and Anticipated Selection

This second survey also shows that differences between PASS students concerning the reform depend less on pre-admission factors (gender, social class, high school attended) than on the experience of their year of access to health studies. Their opinions thus vary according to the chosen minor, most students believing that some minors were more difficult to validate than others because of significant differences on workload and teachers’ expectations regarding evaluation. This leads some of them, even if they are receptive to the advantages offered by minors in the event of failure, to criticise the resulting possible unfairness: ‘If 50% of the students [of this minor] accepted for the 2nd year are rejected because they did not get a grade of 10 for their minor, then there is a problem. The minor is supposed to enable students’ reorientation. If it prevents students from getting their first choice, then there is a failure of the reform.’ (Pierre, PASS)

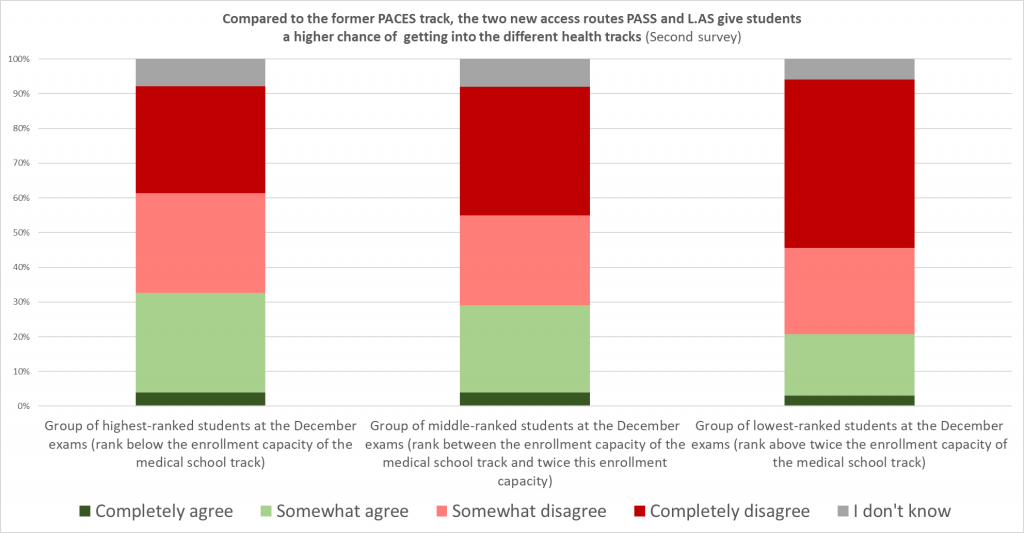

Unsurprisingly, positive opinions expressed by students on the chance of getting accepted into health studies thanks to the reform decrease according to the grades and ranking obtained in the first exams in December.

Read: 4% of the students having a rank below the enrollment capacity of the medical school track at the December exams “totally agree” with the statement “Compared to the former PACES track, the two new access routes PASS and L.AS give students a higher chance of getting into the different health tracks.

Past rankings thus have a strong influence on the students’ opinions, but the influence of future rankings, which are the most decisive, is even stronger. Indeed, the importance of the oral exam in the final ranking is what provokes the strongest criticism. Even though many students appreciate being evaluated on several criteria, they believe that written exams demand more preparation and should therefore have more weight in the final ranking. Once again, this illustrates the importance they place on the association between merit and effort, as fair competition should reward hard work: ‘The orals, we were quite happy to begin with, because I find it really interesting that there are oral exams. So, it is not just based on written exams and maths. But I didn’t think the orals would count as much for getting into the health tracks. (…) Because if someone with a poor ranking does very well at the oral and goes up in the rankings even though they didn’t work more than a month for the written exams, there will be some unfairness.’ (Alexis, PASS)

This negative perception before the orals had taken place was later greatly enhanced by its organisation and effects, even resulting in students from some universities challenging the final rankings of the admission into health studies exam before the “Conseil d’Etat”, as reported in the media(10)see for example “PASS/LAS : les étudiants éliminés à l’oral portent leur combat devant la justice“, What’s up Doc, 3 august 2021. We have not yet collected the students’ opinions after this exam, but those of two parents interviewed in July 2021 confirm the different aspects underlying the students’ indignation reported in the media: the lack of preparation of the members of the jury; exam subjects considered completely unrelated to health studies (even considering the standpoint of a ‘more human’ training course for doctors); above all, a grade calculation process giving more weight to the oral exam than to the written exams.

Conclusion

Students’ perspectives do not generally question the status quo, nor the many changes introduced in universities, which can lead observers to consider them as ‘weak’ players, with no influence on decisions(11)Payet J.P., 2012, « « L’acteur faible » : une figure emblématique des institutions contemporaines » – The weak actor: an emblematic figure of contemporary institutions – in F. Aballea (ed.) Institutionnalisation, désinstitutionalisation de l’intervention sociale (p.65-71), Octarès.. As shown by the reform of the admission process in health students, pragmatic acceptance nevertheless gives way to more openly dissenting attitudes if the students believe that the meritocratic contract on which their acceptance is based has been broken. Aside from its political implications, this observation invites researchers to consider student perspectives from two angles: their contribution to the ordinary activity of educational institutions but also to the reaffirmation of their underlying principles.

The evaluation of health policies is one of the main research areas of Sciences Po’s Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policies (LIEPP). Funded by the French Research Agency (ANR)’s “Investments for the Future” programme, the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policies is a research platform, and now works in partnership with Université de Paris. It has developed and implements an innovative evaluation approach. Innovative because it associates quantitative, qualitative and comparative methods; innovative because it compares disciplinary viewpoints of the evaluated policies; innovative because of its hybrid nature, combining methodological and theoretical knowledge from different disciplines with that of international evaluation. The Health policies research group, created in 2020, originated from a partnership with Université de Paris, which brought together human and social sciences with the so-called “hard” sciences. Co-directed by Henri Bergeron (Sciences Po, Centre for the Sociology of Organisations) and Thomas Rapp (Université de Paris, LIRAES), it aims to report on the proliferation of evaluations of health policies and instruments, both nationally and internationally. Finally, the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policies also contributes to the public debate and discussions on evaluation involving other stakeholders (administrations, parliament, non-governmental organisations, etc.), in an effort to promote the evaluation approach and to improve its quality. Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policies thus co-organised a series of seminars, coordinated by the Sciences Po Health Chair: What does the future hold for organising primary health care in France? (in French). Notes

In terms of topics, the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policies studies public policies related to key societal challenges: environmental risks, inequalities and discriminations, democracy, socio-fiscal policies, educational policies, health policies.

Health matters are also addressed by other Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policies’ research groups that examine “mixed” issues: handicap and health inequalities; scientific scepticism and defiance with regard to public health policies; medical studies reform; health risks due to environmental deterioration; social and fiscal systems in the field of health care.

↑1 The research presented in this article corresponds to the second axis of a research project on the French reform of access to health studies, coordinated by Agnès van Zanten, and was conducted by Alice Olivier (co-coordinator of the axis with A. van Zanten), Christophe Birolini, Audrey Chamboredon and Léon Marbach. The research includes a two-part survey sent to a sample of first-year students (N= 879 for part 1, December 2020; N= 635 for part 2, March 2021) and two series of interviews with around forty students. This project is supported by a public grant overseen by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the “Investissement d’Avenir” program.

↑2 Revillard A., 2018, « Saisir les conséquences d’une politique à partir de ses ressortissants : la réception de l’action publique » – Understanding the consequences of a policy based on its nationals: the reception of public action – Revue française de science politique

↑3 van Zanten A., 2018 – « La fabrication familiale et scolaire des élites et les voies de mobilité ascendante en France » – “How families and schools produce an elite. Paths of upward mobility in France – in A. van Zanten (ed.) Elites in Education, Londres, Routledge, coll. Major themes in education, 2018

↑4 Dubet F. Les lycéens, Paris Seuil ; Dubet F., 2004, L’école des chances, Paris, Seuil.

↑5 van Zanten A. 2021, Les Politiques d’éducation (4e ed.), Paris, PUF.

↑6 “Mise en œuvre de la réforme de l’accès aux études de santé : un départ chaotique au détriment de la réussite des étudiants (Implementation of the reform of access to health studies: a chaotic start detrimental to students’ success), Information report no. 585 (2020-2021) by Ms. Sonia de la Provôté, written on behalf of the culture, education and communication commission, registered 12 May 2021.

↑7 Becker H., Geer B., Hughes EC. et Strauss A.L., 2003 (1961), Boys in White. Student Culture in Medical School, New Brunswick, Transaction Publishers.

↑8 Becker H., Geer B.et Hughes E.C., 1995, Making the Grade. The Academic Side of College Life, New York, Routledge.

↑9 Olivier A., Oller A.C., van Zanten A., 2018, «Channelling students into higher education in French secondary schools and the re-production of educational inequalities. Discourses and devices», Etnografia e Ricerca Qualitativa.

↑10 see for example “PASS/LAS : les étudiants éliminés à l’oral portent leur combat devant la justice“, What’s up Doc, 3 august 2021

↑11 Payet J.P., 2012, « « L’acteur faible » : une figure emblématique des institutions contemporaines » – The weak actor: an emblematic figure of contemporary institutions – in F. Aballea (ed.) Institutionnalisation, désinstitutionalisation de l’intervention sociale (p.65-71), Octarès.