When the Truth is Inconvenient or “Motivated” Reading of Information

13 February 2020

Transforming universities: Proposals from a researcher

13 February 2020![]() In her most recent work, Colonial Transactions: Imaginaries, Bodies, and Histories in Gabon (Duke University Press, 2019), historian of Sub-Saharan Africa and researcher at the Centre d’histoire, Florence Bernault examines sites and moments in which colonised and colonialists negotiated ideas, things, power and status. The book deconstructs a vision of Africa during colonialism as a binary world with few common imaginaries.

In her most recent work, Colonial Transactions: Imaginaries, Bodies, and Histories in Gabon (Duke University Press, 2019), historian of Sub-Saharan Africa and researcher at the Centre d’histoire, Florence Bernault examines sites and moments in which colonised and colonialists negotiated ideas, things, power and status. The book deconstructs a vision of Africa during colonialism as a binary world with few common imaginaries.

Why did you write this book?

Florence Bernault: This book is the continuation of my work on the political and cultural history of Central and Equatorial Africa, and the transformations that occurred during and after the colonial period. But the main question of this book is the history of power. I argue that congruent imaginaries of power existed among Europeans and Africans imaginaries including about supernatural agency and witchcraft.

What questions does your work strive to answer?

F. B. : Twenty years ago, the anthropology of “modern witchcraft” opened up exciting new avenues of inquiry on the role of the occult and magic in Africa. Yet few scholars examined these questions in a historical perspective. Contrary to conventional thinking, colonial domination strongly interfered with local cultures of magic and the supernatural, in particular by criminalising magic, and by imposing new vocabularies on the occult. This book is an attempt to understand the effects of colonialism on such imaginaries, and the ways in which the French and the Gabonese interpreted how one could act on oneself and others.

What are the sources that have enabled you to explore this topic?

Louis Bouquet, Apollon et sa muse “négresse”, Palais de la Porte Dorée, ancien musée des Colonies, 1931

F. B. : My work tries to connect historical and anthropological sources collected during lengthy archival and field work in Gabon. For example, to trace how cannibalism became a central imaginary of power in the region, I compiled colonial court records by cross-referencing them with contemporary urban rumors about the sale of human organs, anthropological work on sacrificial rituals, and missionary records on the Eucharist in local churches.

What does the term colonial transactions correspond to?

F. B. : I have imported the term transaction – mainly used in economics – into the field of human sciences, where the notion has rarely been utilized outside of psychology and anthropology. To my knowledge, no historians have used the concept as a tool of analysis. And yet, if you look at exchanges and interactions between Europeans and Africans as transactions (whether positive or negative, voluntary or involuntary), the concept provides greater insight into how these actors could share moments of joint action where ideas, things, power and status were negotiated. Transaction looks at experiences of confrontation, exchange or avoidance between colonialists and Africans as genuine social acts. It is a more interactive and transformative concept than that of “borrowing”, for example, and a more relational notion than “resistance”.

Rather than any abstract decision, I constructed the tool by being inspired by field and archival sources . Colonial actors, both African and French used “transactional imaginaries.” Foreign domination, as well as local forms of power, relied constantly on such transactional imaginaries that explained how action, status and power derived from exchanges in objects, money, ideas, words and gifts. The French, for instance, justified colonisation through a foundational exchange: they believed that African taxes and other contributions were supposed to match France’s ‘‘sacrifice’’ of ‘‘offering’’ Africans the benefits of civilisation, technical innovation, and moral progress. A particularly detailed study of this imaginary has been described by Alice Conklin in A Mission to Civilize. The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895-1930 (1997). On the African side, composing powerful objects and therapeutic rituals mostly occurred through transactions with spirits and ancestors.

Give us an example of these historical reconstructions

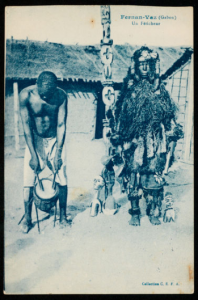

Fernan-Vaz (Gabon) Un féticheur, Collection C.E.F.A. © musée du Quai Branly

F. B. : My idea was to understand how African and European imaginaries of power coincided and transformed between the 19th and 21st centuries. I tried to find particular fields and objects where these imaginaries became historically condensed.

For example, one chapter explores how Europeans, at the beginning of the 19th century, expressed only disgust and repulsion about local charms and fetishes . Their taste changed at the turn of the 1840s and 1850s, when they began acquiring certain local objects. We know how such objects subsequently circulated in long distance commercial networks, and entered art collections and exhibitions in European museums and galleries. What is less known, and what I explain in my book, is how these transactions occurred in the field, at the grassroots, and what was the point of view of the Africans selling these objects, giving them away, or having them confiscated.

One chapter is devoted to Mami Wata. Can you tell us more ?

F. B. : In the new acquisitions at the Musée du Quai Branly there is a statue of Mami Wata that comes from Benin. You can enjoy the object for its aesthetic qualities and the story of its fabrication. But my book also explains how this kind of object embodies the history of local and foreign imaginaries about power and riches. Before the Europeans arrived in Gabon, a local Mami Wata worked as a blacksmith spirit who gave metal to local communities. During colonialism, Mami Wata had to compete with European steel techniques and was eventually vanquished. Her worshippers abandoned Mami Wata, while carving a statue of a Siren as municipal emblem. The story of the statue represents complex historical struggles between local and foreign techniques for the production of wealth.

What about cannibalism, which is also a central part of the book?

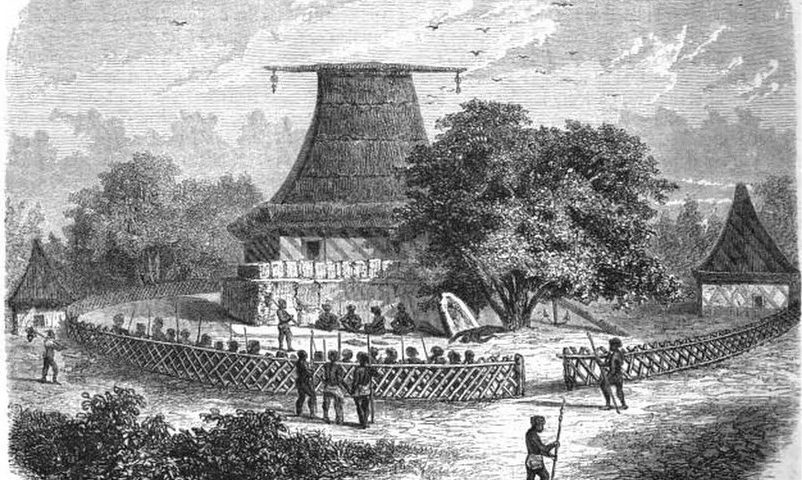

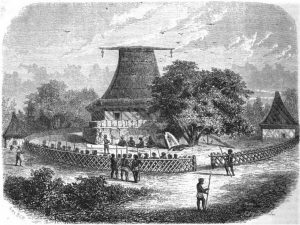

Illustration from Alexandre de Bar’s book – Le Tour du Monde (1860) representing a house of spirits and a scene of cannibalism.

F. B. : In Gabon today, many rumors and controversies circulate about cannibalism and vampirism. People believe that local elites use ritual murders and organ trafficking to strengthen their power. I posit that these anxieties have everything to do with the complex transformations of imaginaries of power during the colonial period.

Cannibalism was an key imaginary in the European understanding of Central Africa, and particularly of Gabon. In 1861,Paul du Chaillu described the Fang– in a totally mistaken way – as ruthless cannibals who killed victims and cut them up to eat their flesh. The misunderstanding deployed in very concrete colonial policies. In 1923, a ministerial decree on “the suppression of anthropophagy and trafficking in human remains” led administrators to ‘‘find the cannibals’’ in the field. They investigated incidents, fabricated evidence, and arrested suspects, executing dozens of people between the 1920s and 1950s. The Gabonese imaginary around ‘‘eating’’ (a verb that derives from a highly complex social and cosmological system) changed dramatically. People began to harbour greater fears that the power of the few, the elite, was based on real cannibalism, on the destruction and ingestion of bodies. This had not been the case in the 19th century, even at the time of the slave trade.

What is the main conclusion that can be drawn from this work?

F. B. : Colonial Transactions challenges the perspective that Africa and Europe differ entirely from each other, whether in the area of technological systems, mental worlds or historical trajectories. It shows that, historically, important forms of compatibility and complementarity existed in the cosmologies and moral worlds used by Euro-Americans and Africans. It also suggests that the colonial period can be explored as a time of shared irrationalities and fantasies.

Interview by Anne Ruel, historian

Florence Bernault is Professor of African History at the Sciences Po Center for History. Her works focuses on the political and cultural history of Equatorial Africa since the nineteenth century. She looks at how local institutions and imaginaries have transformed during colonialism, anchoring her queries in contemporary dynamics and the immediate history of Congo-Brazzaville and Gabon.