From Populism to Populisms

19 May 2021

When Courts are the Metronome of Productivity

8 July 2021Candidates’ Transnational Linkages on Twitter During the 2019 European Parliament Elections

By Caterina Froio, CEE

As the European Union (EU) still has to prove its democratic character in the eyes of many observers, the direct elections of the European Parliament (EP) served as litmus tests. So far, they have been described as second-order events for citizens, somehow too far from everyday domestic politics to matter. However, three main changes in EU politics hold the potential for an increased transnational character of the 2019 EP elections. First, the Spitzenkandidaten (lead candidates) system which increased the personalisation in EP election campaigns was applied again. Linking the outcomes of national votes to the selection of the President of the European Commission has the potential to increase public awareness of EU affairs. Second, the political consequences of the multiple crises the EU has had to face, notably the Great Recession and the refugee policy crises, increased the politicisation of the EU in domestic debates(1)Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2019). ‘Politicizing Europe in Times of Crisis’, Journal of European Public Policy.. Such crisis dynamics might also stimulate transnational campaign activity. Third, EU politics had become more contested notably by radical right populist parties (RRPPs)(2)Pirro, Andrea Lp., Paul Taggart, and Stijn Van Kessel (2018). ‘The Populist Politics of Euroscepticism in Times of Crisis: Comparative Conclusions’, Politics. RRPPs engaged in Eurosceptic campaigns beyond national borders, at times creating cross-national linkages and mobilising on transnational issues such as EU integration, migration, and economic governance(3)McDonnell, Duncan, and Annika Werner (2019). International Populism: The Radical Right in the European Parliament. London: C Hurst & Co; Froio, Caterina, and Bharath Ganesh (2019). ‘The Transnationalisation of Far Right Discourse on Twitter’, European Societies.. To shed light on these trends, the study is driven by two main questions:

- To what extent are EP candidates’ campaign interactions transnational?

- Under what conditions do EP candidates engage in transnational campaign interactions?

To address these, we analysed the campaign behaviour of EP candidates using digital behavioural data. We rely on more than half a million tweets sent during the 2019 EP election campaign by 2,799 candidates belonging to the major parties in the 28 EU member states. The data has been collected in the project ‘What do the people want? Analysing Online Populist Challenges to Europe’.We use the Chapel Hill Expert Surveys to measure party positions on the EU.

Social Media’s Potential for the Transnationalisation of EU Politics

Theoretical work on the (missing) European public sphere has emphasised the role that media have played for Europeanisation processes(4)Polk, Jonathan, et al. (2017). ‘Explaining the Salience of anti-Elitism and Reducing Political Corruption for Political Parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey Data’, Research & Politics.(5) Habermas, Jürgen, and Ciaran Cronin (2012). The Crisis of the European Union: A Response. Polity., notably in terms of the impact of EU politicisation on the emergence and development of a transnational political arena. More recently, scholars have highlighted the potential of social media for political interactivity beyond national public spheres and thus as facilitators for transnationalisation(6)Ruiz-Soler, Javier, Luigi Curini, and Andrea Ceron (2019). ‘Commenting on Political Topics through Twitter: Is European Politics European?’, Social Media + Society.. Optimistic accounts of social media’s transnational potential have identified signs of a ‘European Twittersphere’ and Twitter’s potential ‘to generate a European demos’. However, despite a non-neglectable participation by users in cross-national debates(7)Bossetta, Michael, Anamaria Dutceac Segesten, and Hans-Jörg Trenz (2017). ‘Engaging with European Politics Through Twitter and Facebook: Participation Beyond the National?’, in Mauro Barisione and Asimina Michailidou (eds.), Social Media and European Politics: Rethinking Power and Legitimacy in the Digital Era. Palgrave Macmillan UK, social media’s potential for transnationalisation should not be overestimated as they are used by a relatively tiny share of citizens for political purposes.Yet with its ‘elitist’ nature(8)Stier, Sebastian, Wolf J. Schünemann, and Stefan Steiger (2018b). ‘Of Activists and Gatekeepers: Temporal and Structural Properties of Policy Networks on Twitter’, New Media & Society, Twitter is a social network widely used by political actors, e.g. 85% of the Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) who served in 2015 and 2016(9)Daniel, William T., Lukas Obholzer, and Steffen Hurka (2019). ‘Static and Dynamic Incentives for Twitter Usage in the European Parliament’, Party Politics..Accordingly, we study campaign activities by all candidates with a Twitter account who stood in the 2019 EP campaign for the major national parties.

It would be misleading to simply expect transnational activity to take place in some kind of ‘artificial supranational space’, located, ‘above and beyond local-, national- or issue-specific public spheres’(10)Risse, Thomas (2014a). ‘European Public spheres, the Politicization of EU Affairs, and Its Consequences’, in Thomas Risse (ed.), European Public Spheres. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Therefore, we introduced and examined the transnational campaign arena as a communicative sphere that cross-cuts the national and supranational levels. Specifically, we conceptualise two different but complementary types of interactions structuring transnational campaign activities: (1) horizontal transnational interactions between EP candidates from two different member states and (2) vertical transnational interactions between EP candidates and the main transnational reference points during the campaign, Transnational Parties (TNPs) or Spitzenkandidaten.

Candidates’ Engagement in the Transnational Campaign Arena: Driving Factors and Counterforces

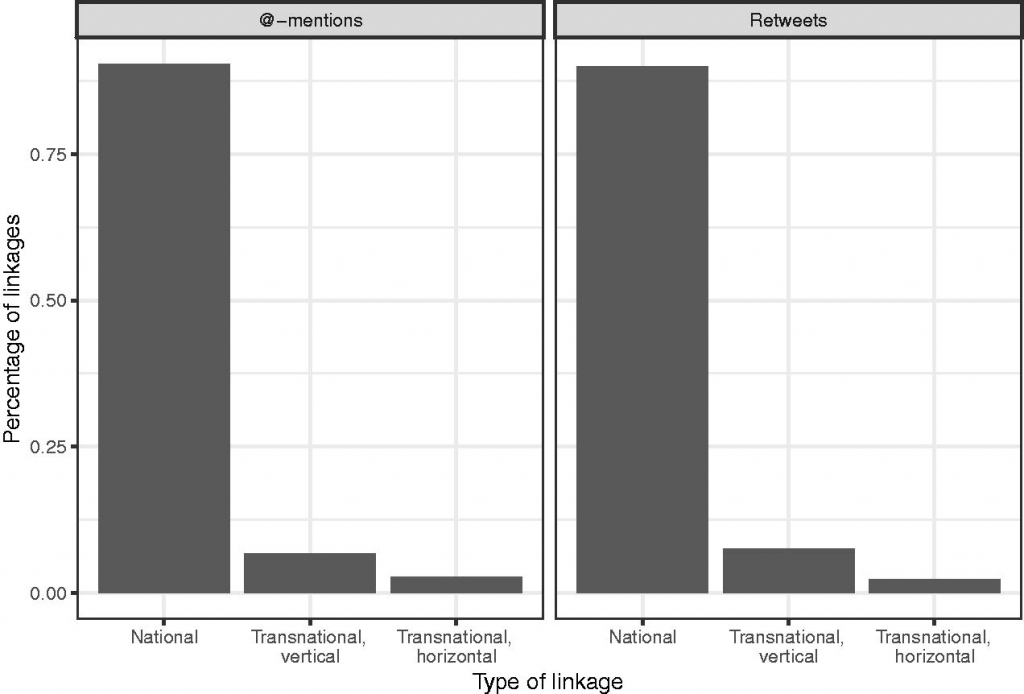

Figure 1 shows the type of communicative linkages in tweets by EP candidates, in terms of @-mentions and retweets. It illustrates that candidates overwhelmingly interacted with other candidates from the same country and only rarely addressed transnational actors (vertically) or their counterparts (horizontally) from other countries. The sheer number of domestic interactions clearly signals that the primary political arena for EP campaigns is still national, supporting the second-order election hypothesis.

Figure 1. Types of communicative linkages in tweets by EP candidates.

Source: Stier, Sebastian, Caterina Froio, and Wolf J. Schünemann (2020). ‘Going transnational? Candidates’ transnational linkages on Twitter during the 2019 European Parliament elections.’ West European Politics

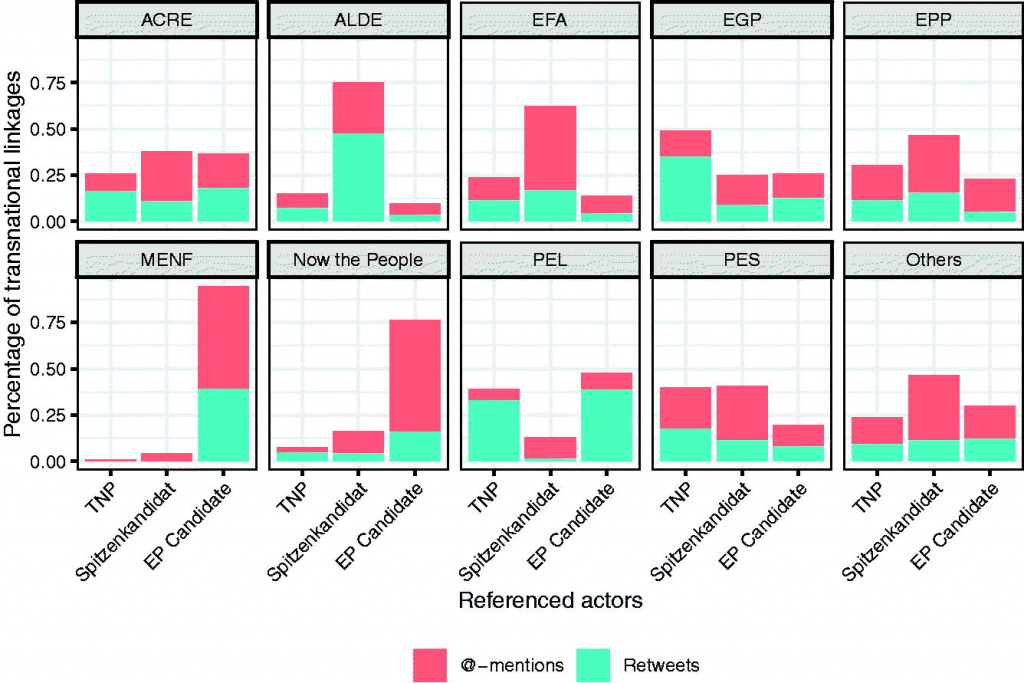

To continue the investigation, Figure 2 displays the types of transnational communicative linkages in tweets by EP candidates, aggregated by TNP. It appears that candidates from Europhile parties with ambitions to promote one of their lead candidates to the presidency of the EU Commission (ALDE, EPP and PES) prominently emphasise Spitzenkandidaten in their tweets. In contrast, candidates of RRPPs grouped in the MENF that did not nominate a Spitzenkandidat never retweet one, but occasionally @-mention a Spitzenkandidat, supposedly as a negative campaigning tactic.

Figure 2. Types of transnational communicative linkages in tweets by EP candidates aggregated by TNP.

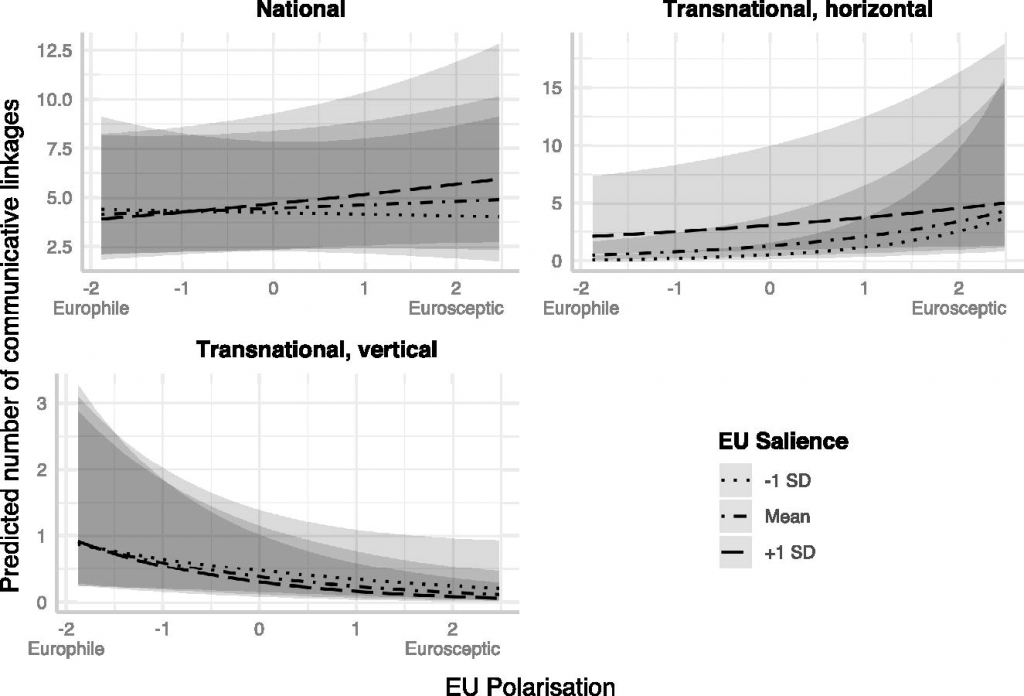

Note: Marginal effects including 95% confidence intervals are shown for the mean, one standard deviation below and above the mean value of EU Salience.

Note: Abbreviations of party names: ACRE = Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists; ALDE = Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe; EFA = European Free Alliance; EGP = European Green Party; EPP = European People’s Party; MENF = Movement for a Europe of Nations and Freedom; PEL = Party of the European Left; PES = Party of European Socialists; Others = Candidates from parties without TNP affiliation, independent candidates or minor TNPs such as the European Pirate Party.

In order to put these results on a more robust footing, we performed multivariate analyses (not shown). We find that candidates from parties whose TNP nominated a Spitzenkandidat have a higher share of vertical transnational communicative linkages, in line with the descriptive patterns presented before. The effect of having a Spitzenkandidat is not significantly related to horizontal and national linkages. Eurosceptic party positions with regard to the EU are positively associated with horizontal linkages and negatively associated with vertical linkages.

In addition, Figure 3 visualises to what extent the predicted marginal effect of EU Polarisation varies across levels of EU Salience. The plot shows that there are no significant differences depending on the levels of EU Salience (visualised are the predictions for the mean, one standard deviation below and above the mean of EU Salience), but that parties’ EU positions still matter. Candidates of parties with anti-EU positions are less likely to engage in the vertical dimension of the transnational campaign arena. However, we also find that Eurosceptic parties have an even higher likelihood to engage horizontally with candidates from other countries.

Figure 3. Predicted number of communicative linkages for the interaction EU Polarisation and EU Salience

A qualitative look at the data helps illustrate this pattern: the two national parties with the highest amount of horizontal linkages (153) among each other are the far-right Eurosceptic parties Lega (CHES EU position ¼ 1.5 on a scale from 1 to 7; M¼4.77) and Rassemblement National (1.05). On the far-left Eurosceptic end of the political spectrum, there is a cluster consisting of La France Insoumise (2.25), the Swedish Vänsterpartiet (2.47) and Danish Red – Green Alliance (1.82) that regularly linked to each other horizontally.

Conclusion

Even on social media there is still no EU public sphere but some factors can contribute to form it. The study shows that candidates primarily direct their campaign communication towards the national arena, even on the elite-dominated social network Twitter. A more nuanced picture emerged when concentrating on the drivers of transnational communication on Twitter. We observed that the Spitzenkandidaten receive even more vertical transnational linkages than the much-longer-established TNPs. This suggests that the Spitzenkandidaten system might serve as a relay for transnational activity that could pave the way for further institutional reform. To pour some cold water on this affirmative conclusion, it is important to note that the interaction of candidates with Spitzenkandidaten varies considerably across party families.

Furthermore, the findings show that political parties that have clearer pro- or anti-EU positions are more likely to attach more importance to different types of transnational exchanges. Candidates from Europhile parties that put a strong emphasis on the EU embrace the opportunity to engage with actors like TNPs and Spitzenkandidaten vertically. Eurosceptic parties, in contrast, address supranational actors in their Twitter communication sparsely and are even more likely to engage horizontally across borders. More generally, our findings suggest that engagement (and interest) in EP campaigns is not only the realm of Europhile actors. In fact, while transnationalisation is often normatively associated with pro-EU orientations, we show that it can also stem from Eurosceptic campaigns.

Taken together, our findings suggest that further institutional reforms would be needed to overcome the predominant national orientation of the EP election campaigns. The fact that the appointment of the President of the Commission in 2019 did not follow the logic of the Spitzenkandidaten system casts doubt on such endeavours. One suggestion is to promote cross-country candidate lists which – in line with our findings – could further transnationalise EP election campaigns.

Notes

| ↑1 | Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2019). ‘Politicizing Europe in Times of Crisis’, Journal of European Public Policy. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Pirro, Andrea Lp., Paul Taggart, and Stijn Van Kessel (2018). ‘The Populist Politics of Euroscepticism in Times of Crisis: Comparative Conclusions’, Politics. |

| ↑3 | McDonnell, Duncan, and Annika Werner (2019). International Populism: The Radical Right in the European Parliament. London: C Hurst & Co; Froio, Caterina, and Bharath Ganesh (2019). ‘The Transnationalisation of Far Right Discourse on Twitter’, European Societies. |

| ↑4 | Polk, Jonathan, et al. (2017). ‘Explaining the Salience of anti-Elitism and Reducing Political Corruption for Political Parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey Data’, Research & Politics. |

| ↑5 | Habermas, Jürgen, and Ciaran Cronin (2012). The Crisis of the European Union: A Response. Polity. |

| ↑6 | Ruiz-Soler, Javier, Luigi Curini, and Andrea Ceron (2019). ‘Commenting on Political Topics through Twitter: Is European Politics European?’, Social Media + Society. |

| ↑7 | Bossetta, Michael, Anamaria Dutceac Segesten, and Hans-Jörg Trenz (2017). ‘Engaging with European Politics Through Twitter and Facebook: Participation Beyond the National?’, in Mauro Barisione and Asimina Michailidou (eds.), Social Media and European Politics: Rethinking Power and Legitimacy in the Digital Era. Palgrave Macmillan UK |

| ↑8 | Stier, Sebastian, Wolf J. Schünemann, and Stefan Steiger (2018b). ‘Of Activists and Gatekeepers: Temporal and Structural Properties of Policy Networks on Twitter’, New Media & Society |

| ↑9 | Daniel, William T., Lukas Obholzer, and Steffen Hurka (2019). ‘Static and Dynamic Incentives for Twitter Usage in the European Parliament’, Party Politics. |

| ↑10 | Risse, Thomas (2014a). ‘European Public spheres, the Politicization of EU Affairs, and Its Consequences’, in Thomas Risse (ed.), European Public Spheres. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press |