Waiting for a Transnational EU Public Sphere

8 July 2021

Evaluating Environmental Policies

8 July 2021By Johannes Boehm, Department of Economics

Over the last decades, researchers have pointed out that firms in developing countries are less productive than their counterparts in developed countries. These firms face large distortions in factor markets, which leads to inefficient allocation of factor inputs and organisational forms. These distortions are so big that their removal would likely lead to large increases in industrial productivity and the level of development of these countries. Where do these distortions come from? And how do these distortions affect a firm’s production decisions and its productivity at regional or national levels ?

In a series of articles, Johannes Boehm, Assistant Professor at the Department of Economics, studies the role that frictions play in the contracting process (breach of contract, improper contract performance, …) between firms on firm-level outcomes, such as organisation and productivity, and the degree to which they determine macroeconomic outcomes such as per-capita income(1)This work is informed by the observed structure of production of firms, which researchers measure through data coming either directly or indirectly from firm censuses..

The Impact of Contracting Frictions on Supplier Selection

Contracting frictions affect firms in their decisions to source intermediate inputs. When trading partners are not able to rely on the timely enforcement of their contracts, they may be limited in their choice of suppliers (to longstanding associates or to family members, owners of related businesses, who can produce the requested inputs), or may even have to produce the inputs themselves by vertically integrating the production process. Regardless of their chosen alternative, they will be forced to produce at a higher cost, which is in turn passed on to firms further downstream in the value chain and, ultimately, the consumers. Intermediate inputs that are tailored specifically to the buyer (‘relationship-specific’ intermediate inputs) are particularly prone to contracting imperfections (elements that limit its effectiveness) because of their limited specific input’s resale value in case of dispute and are therefore more dependent on formal court enforcement.

Performance of the Judicial System is Crucial

The most important institutional determinant of these frictions is the quality of the court system. Countries differ vastly in the speed and quality of contract enforcement: while courts in Iceland, Singapore, and other high-income countries resolve disputes within months, years- or even decades-old cases are commonplace in the developing world.

The problem of contracting frictions due to congested courts is particularly salient in the case of India. India has long been struggling with slow and congested courts. Since the 1950’s, the Law Commission of India has repeatedly highlighted the enormous backlogs and suggested policies to alleviate the problem, but with little success. Occasionally these delays make international headlines, such as when eight executives were found guilty and convicted in the first instance for the 1984 Bhopal disaster in… 2010(2)cf. “Painfully slow justice over Bhopal“, Financial Times, June 2010. One of them had already passed away, and the other seven have since appealed the conviction.

The Link Between Justice and Productivity

In a recent publication in the Quarterly Journal of Economics(3)Johannes Boehm, Ezra Oberfield, Misallocation in the Market for Inputs: Enforcement and the Organization of Production, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, November 2020, Johannes Boehm and Ezra (Princeton University) study the relationship between the intermediate input mixes (i.e., the raw materials consumed during the production process) of plants in the Indian manufacturing sector, and the quality of the court system.

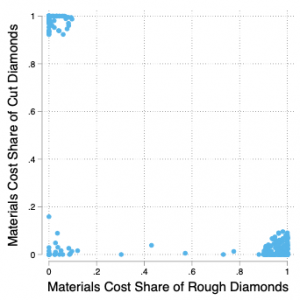

A key feature of the dataset is that it contains detailed product-level information on each plant’s intermediate inputs and outputs. These data on inputs allow to better distinguish between different organisational modes of production. As an example, Figure 1 shows different input mixes among plants that produce polished diamonds. The manufacturing plants are similar but their production processes are different: certain plants that produce polished diamonds from raw diamonds will do both cutting and polishing, while others will produce polished diamonds from cut diamonds and just do the polishing. These different input mixes correspond to the degree of vertical integration of the plants(4)The difference between input mixes determines the degree of vertical integration of manufacturing plants. A plant that has a limited choice of suppliers for its inputs may decide to produce them itself (vertical integration). For example, a plant that produces polished diamonds from raw diamonds may choose to do both the cutting and polishing itself if it cannot find a supplier of cut diamonds whereas the plant that does have the latter, will only have to polish the diamonds..

Figure 1- Heterogeneity in input mixes within industries of the same sector

Disparities between states

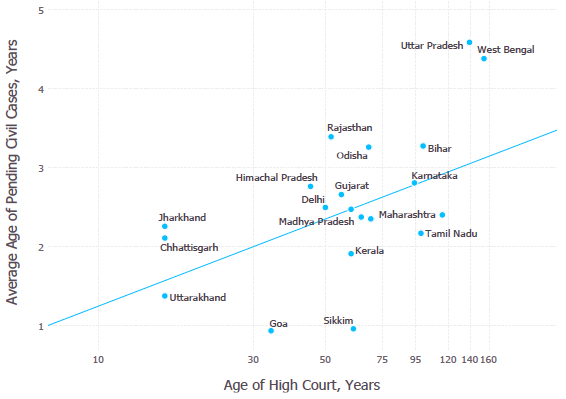

We relate the plants’ expenditures on different types of inputs to court delays in its state. We measure court delays as the average age of pending High Court cases. Delays vary starkly across states: the mean case is one year old in the fastest state (Goa), and four and a half years in the slowest state (Uttar Pradesh). We also use an instrumental variable building on the fact that the court speed is largely determined by the age of the court.

Figure 2- Age of the High Court and speed of enforcement

The data show that the use of materials in production is systematically distorted where courts are slow. In particular, in industries that tend to rely on specific inputs, plants will tilt their input mix towards the use of homogeneous (non-relationship-specific) intermediate inputs. Moreover, plants in industries that tend to rely heavily on specific inputs are more vertically integrated (ie companies supporting more manufacturing steps) when located in states with more congested courts.

How much do these distortions matter?

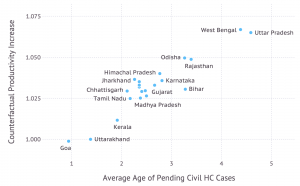

The researchers estimate a model to quantify the impact of court delays on aggregate productivity. In the model, producers in each industry face decisions regarding the degree of vertical integration of production, as well as from which suppliers to buy . By comparing the model predictions to the data, the researchers estimate the strength of the distortions, and simulate aggregate productivity under a scenario in which court congestion is reduced to be in line with the least congested state. On average across states, the boost to productivity is roughly 4%, and the gains for the states with the most congested courts are roughly 7% (Figure 3). These estimates suggest that the economic benefits to improving courts of justice are great.These estimates, however, only measure this mechanism, and there are many other ways that improved contract enforcement could increase productivity and welfare, for example by improving access to capital and labour.

Figure 3- Counterfactual increases in aggregate productivity

Notes: The figure shows the counterfactual increases in aggregate manufacturing sector productivity if the average age of pending cases were set to one year (1.00 = no change)

Ces estimations suggèrent que les gains économiques de l’amélioration des systèmes judiciaires seraient significatifs. Cependant, ces estimations ne prennent en compte que la question de la vitesse des tribunaux. Or, il existe d’autres options qui permettent d’augmenter la productivité et le bien-être, en améliorant, par exemple, l’accès au capital et au travail.

The issue of a functional judicial system may be linked to questions other than its speed

An article forthcoming in the Review of Economics and Statistics shows that the role that contracting frictions take in distorting sourcing and production decisions is true beyond the Indian context; in fact these frictions are present in many countries(5)Boehm, J., 2021. The impact of contract enforcement costs on value chains and aggregate productivity. Forthcoming, Review of Economics and Statistics.. These accounts show that the same industries use disproportionally less services inputs and relationship-specific inputs in developing countries.

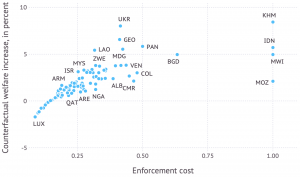

But do these patterns of input use differences arise also because of contracting frictions? That is not immediately clear: developing countries could simply be facing higher costs of producing these customized inputs. To tease apart these two possible explanations, the article uses data on contract-related litigation between firms in the United States to determine the industry-pair-level driver of contracting problems. A quantification exercise again reveals that contracting frictions matter for aggregate outcomes but they do not result from a sluggish court system. Rather they are related to the cost of litigation(6)General category including court costs, lawyers’ fees, etc. to have the contract enforced by the court. By reducing enforcement costs to US levels (14% of the value of the claim, according to the World Bank) some countries could increase their per-capita income by several percentage points (Figure 4).

Figure 4 — Counterfactual increases in per-capita income when enforcement costs are set to US levels

These papers highlight the economic importance of functional, efficient contracting institutions. The underlying causes of enforcement frictions vary across countries: in some countries, like India, they arise because of slow and congested courts, whereas in other countries it is because the cost of legal representation is prohibitively high. Sometimes these two causes are even cumulative. As a result, reform must target these underlying determinants. The benefits, however, will be far wider in scope: they will be felt by firms all along the value chains, and by consumers through lower prices.

Notes

| ↑1 | This work is informed by the observed structure of production of firms, which researchers measure through data coming either directly or indirectly from firm censuses. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | cf. “Painfully slow justice over Bhopal“, Financial Times, June 2010 |

| ↑3 | Johannes Boehm, Ezra Oberfield, Misallocation in the Market for Inputs: Enforcement and the Organization of Production, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, November 2020 |

| ↑4 | The difference between input mixes determines the degree of vertical integration of manufacturing plants. A plant that has a limited choice of suppliers for its inputs may decide to produce them itself (vertical integration). For example, a plant that produces polished diamonds from raw diamonds may choose to do both the cutting and polishing itself if it cannot find a supplier of cut diamonds whereas the plant that does have the latter, will only have to polish the diamonds. |

| ↑5 | Boehm, J., 2021. The impact of contract enforcement costs on value chains and aggregate productivity. Forthcoming, Review of Economics and Statistics. |

| ↑6 | General category including court costs, lawyers’ fees, etc. |