Distributing trade maps: the gravity equation

26 October 2018

Researchers and research engineers working on environmental issues

29 October 2018by Florence Faucher and Laurie Boussaguet,

researchers at CEE & LIEPP

Charlie Hebdo, Hyper Cacher at the Porte de Vincennes, Stade de France, the Bataclan and its vicinity: these are all places that now evoke the series of terrorist attacks that struck France in January and November 2015. Many actors and observers presented these “events”, which shocked France and the rest of the world, as critical moments that ended a period of peace that had been expected to last.

Charlie Hebdo, Hyper Cacher at the Porte de Vincennes, Stade de France, the Bataclan and its vicinity: these are all places that now evoke the series of terrorist attacks that struck France in January and November 2015. Many actors and observers presented these “events”, which shocked France and the rest of the world, as critical moments that ended a period of peace that had been expected to last.

How did the public’s perception of these tragedies form? To answer this question, Florence Faucher and Laurie Boussaguet, researchers* associated with the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policies (LIEPP), focused on a frequently neglected dimension of public action: symbols.

Presentation of the findings presented in their article “The Politics of Symbols: Reflections on the French Government’s Framing of the 2015 Terrorist Attacks” (Parliamentary Affairs, June 2017).

Political communication: the role of symbols

As has been shown many times, good communication is key to any successful governmental action. Moreover, it is common for a government to use verbal and non-verbal symbols – like trips – to give its statements greater authority. Solemnity and rituals are “part of the magic of the Republic”. Communication notably serves to highlight the importance that the government attributes to events. At times of crisis, a government also provides interpretations aiming to build an understanding of the reality. The production is all the more important when the going consensus on what “living together” means is suspended or contested.

It was therefore natural for our researchers to conduct a detailed study of the government’s communication in 2015 to understand how the public’s reaction to the attacks developed.

To this end, they conducted many interviews with major actors in the French leadership: the Prime Minister and his aides, aides to the President of the Republic and the Minister of the Interior, members of the Government’s Information Services, etc. They also studied schedules and analyzed official speeches in the first weeks after the attacks.

Feeding the “media beast”

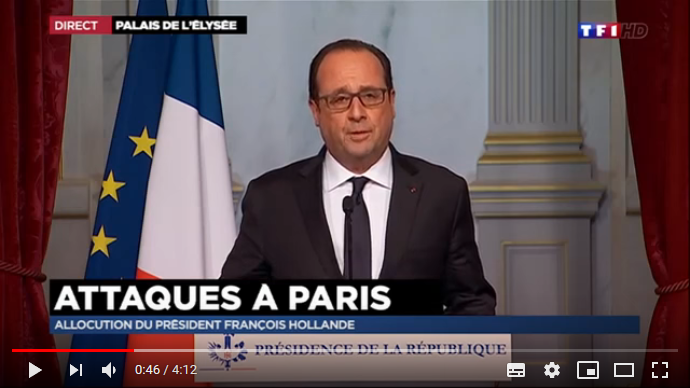

First observation. As interviewed senior officials and advisors put it, in addition to communicating, they also had to adapt to society’s new expectations: a desire for transparency and an implacable need to incessantly “feed the media beast”.  Hence the government’s decision to provide access to images to fill the media space rather than risk seeing it overtaken by political opponents and critics. Thus, the President, Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior appeared in the media via numerous “official” videos and interviews. The president’s actions and decisions were staged to emphasize his reactivity and the importance he placed on the “events”: visits to victims in the hospital, signaling empathy; changes in the presidential agenda to reassure the public; cancellation of non-urgent engagements; convening of the Defense and National Security Council; emphasis on measures to protect the population, etc.

Hence the government’s decision to provide access to images to fill the media space rather than risk seeing it overtaken by political opponents and critics. Thus, the President, Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior appeared in the media via numerous “official” videos and interviews. The president’s actions and decisions were staged to emphasize his reactivity and the importance he placed on the “events”: visits to victims in the hospital, signaling empathy; changes in the presidential agenda to reassure the public; cancellation of non-urgent engagements; convening of the Defense and National Security Council; emphasis on measures to protect the population, etc.

The leadership’s symbolic rhetoric and performance played a decisive role in building a rally phenomenon that combined public support for government action and a relative suspension of criticism from the media and the opposition. They also helped strengthen the legitimacy of the government and the credibility of its actions.

The leadership maximizes its media visibility

Despite the acceleration in the information cycle and the reactions of other political actors, governments to this day are still a few steps ahead and communicate at times when others are sometimes quiet or cautious. For a short period, it remains the only source of reliable information: it speaks with authority and better knowledge that anyone, including the opposition and the media. During this period of time, which can vary in length, “the elasticity of reality” plays in its favor. Over the past few years, this period has shortened with the rapidity of news dissemination over the internet and social networks, the emergence of amateur videos, the media’s ability to get a hold of them, etc. The government must therefore relentlessly work to dominate the mass and social medias.

Thus, in January and November 2015, the government maximized its media visibility to disseminate its interpretative framework and describe and explain events: it offered a diagnosis of the events (their symptoms and causes) and an action plan to address them.

In terms of frameworks, defining the attacks as domestic or international played an important role and helped shape the government’s actions and the public’s reactions. While the Charlie Hebdo terrorists claimed to be acting in the name of an international cause, labeling them as international terrorists was not simple and the President declined to do so.  In his speech of 9 January, he explicitly named the symbolic targets attacked by the terrorists: “Today, the Republic was attacked. The Republic is freedom of expression. The Republic is culture, creation, pluralism, and democracy. That is what the assassins were targeting. It is the ideal of justice and peace that France carries everywhere on the global stage”.

In his speech of 9 January, he explicitly named the symbolic targets attacked by the terrorists: “Today, the Republic was attacked. The Republic is freedom of expression. The Republic is culture, creation, pluralism, and democracy. That is what the assassins were targeting. It is the ideal of justice and peace that France carries everywhere on the global stage”.

Contrariwise, for the November attacks planned abroad, the international terrorism label was applicable and used. This international aspect enabled the introduction of the notion of “war” and justified exceptional measures, sometimes in tension with the rule of law.

This speech shows the importance of repetition as a rhetorical tool to provide a framework and transform the interpretation of the event into a “fact”. The government offered a framework that echoed policies that were simultaneously announced and implicitly served to justify them. The objective was to shape the understanding of events in order to change the power relations and prepare the public for them.

Building a national unit: from “the spirit of 11 January” to a rallying around the flag

The government was particularly sensitive to the need to prevent social fractures and political disunion. In January, political leaders from the other parties and the representatives of various religious communities supported its unity strategy. Hosted by the President, political and religious leaders were interviewed on the steps of the Elysées, surrounded by symbols of the Republic. All called for a “republican response” or invoked the importance of national unity.

The government was particularly sensitive to the need to prevent social fractures and political disunion. In January, political leaders from the other parties and the representatives of various religious communities supported its unity strategy. Hosted by the President, political and religious leaders were interviewed on the steps of the Elysées, surrounded by symbols of the Republic. All called for a “republican response” or invoked the importance of national unity.

The events were presented as unique and requiring national unity. The innovation at the symbolic level seemed logical in response to an event whose symbolic impact was unique. Minutes of silence, flags at half-staff and heightened alert levels no longer sufficed. In January, the silent march appeared as the best way to show respect for the dead and to mark symbolic support for the Republic while avoiding public discourses sowing discord. In the span of a week, the government orchestrated the largest march in Paris since 1944, an international summit, and a moving ceremony at the Prefecture.  For several days, the media was not critical and the Front National found itself in a delicate situation. The government thus succeeded in creating an impression of consensus to the point that “the spirit of 11 January” remains one of the main interpretations of what happened in January 2015. However, in November the state of emergency precluded marches and the population’s participation was limited. At the President’s request, people came together around the flag, which appeared at the windows of residences, Facebook, and other social media.

For several days, the media was not critical and the Front National found itself in a delicate situation. The government thus succeeded in creating an impression of consensus to the point that “the spirit of 11 January” remains one of the main interpretations of what happened in January 2015. However, in November the state of emergency precluded marches and the population’s participation was limited. At the President’s request, people came together around the flag, which appeared at the windows of residences, Facebook, and other social media.

The crisis management process contributed to an awareness of the importance as well as the limits of symbolic politics. To show that the response was not “only symbolic” (that is, without any effect), emphasis was placed on the effectiveness of the language used. While in January the identification of France as a “victim” was accompanied by calls for “unity”, ”solidarity”, and ”fraternity”, the leadership added in November the notions of “war”, “act of war”, and “terrorist army”. The symbolism of unity no longer sufficed. Acts were needed (constitutional reform, police in the streets, raids, military investment), as was an action  discourse.

discourse.

The use of political symbols is never simple because each crisis unfolds in a particular and evolving context. Furthermore, symbols condense a variety of meanings that differentially affect the diversity of population categories. Thus, the context can in various ways constrain the ability to mobilize symbols effectively and the alignment of certain symbols with the circumstances and the public’s reactions.

This article stems form the research project on “Symbolitics” – How to evaluate symbolic politics? conducted as part of the cluster on the evaluation of democracy of the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policy (LIEPP).

Laurie Boussaguet is a professor at the University of Rouen and at the Center for European Studies and Comparative Politics, and is associated with the LIEPP. Her research focuses on the analysis of public action in Europe. Florence Faucher is a professor at the Center for European Studies and Comparative Politics and affiliated with the LIEPP. Her research focuses on political parties and social movements.