Right-wing Populist Vote: Challenging Popular Assumptions

17 May 2021

Does Anger Play Into the Hands of Populism?

17 May 2021by Jan Rovny

© Melinda Nagy, Shutterstock

The democratisation of central and eastern Europe was initially celebrated as a historical success story. A European subcontinent moved from communist authoritarian regimes to reasonably functioning democracies based on competitive political systems with the rotation of power. However, by the second decade of the 21st century, the grapes of democracy started to sour. A number of countries, most notably Hungary and Poland, elected leaders and parties who explicitly aim to circumscribe pluralism, undermine independent media, and limit judicial oversight, establishing what the Hungarian Prime Minister, Victor Orbán, calls “illiberal democracy.”

Academic studies of this democratic backsliding proposes a number of important causes(1)Vachudova, Milada Anna, 2021 « Populism, Democracy and Party System Change in Europe », Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 24.. It focuses primarily on the political and economic transition of the region, suggesting that democratization was largely an emulation of the west, rather than a profound transformation. The economic strains of transition alienated segments of the population and undermined democratic legitimacy(2)Bohle, Dorothee, et Béla Greskovits. 2007. « Neoliberalism, embedded neoliberalism andneocorporatism: Towards transnational capitalism in Central-Eastern Europe. », West European Politics ; Bohle, Dorothee, et Béla Greskovits. 2009. « Varieties of Capitalism and Capitalism tout court. » European Journal of Sociology ; cf. Orenstein, Mitchell Alexander. 2001. Out of the red: building capitalism and democracy in postcommunist Europe, University of Michigan Press.. The expectations of the European Union (EU) that guided the transformation in the context of European accession, induced formal institutional construction and legal adaptation, but did not result in a genuine normative shift(3)Grzymala-Busse, A., & A. Innes. 2003. « Great expectations: The EU and domestic political competition in East Central Europe. » East European Politics and Societies ; Cianetti, Licia, James Dawson et Sean Hanley. 2018. « Rethinking “democratic backsliding” in Central and Eastern Europe– looking beyond Hungary and Poland. » East European Politics.. Once inside the EU, Brussels lost the capacity to control these countries, and the leadership of the region was free to pursue their unscrupulous political aims(4)Bozoki, Andras, & Eszter Simon. 2019. « Two Faces of Hungary » Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989 ; Hanley, Sean, et Milada Anna Vachudova. 2018. « Understanding the illiberal turn: democratic backsliding in the Czech Republic. » East European Politics ; Kreko, Peter, et Zsolt Enyedi. 2018. « Explaining Eastern Europe: Orban’s Laboratory of Illiberalism. » Journal of Democracy ; Sata, Robert, & Ireneusz Pawel Karolewski. 2020. « Caesarean politics in Hungary and Poland. » East European Politics..

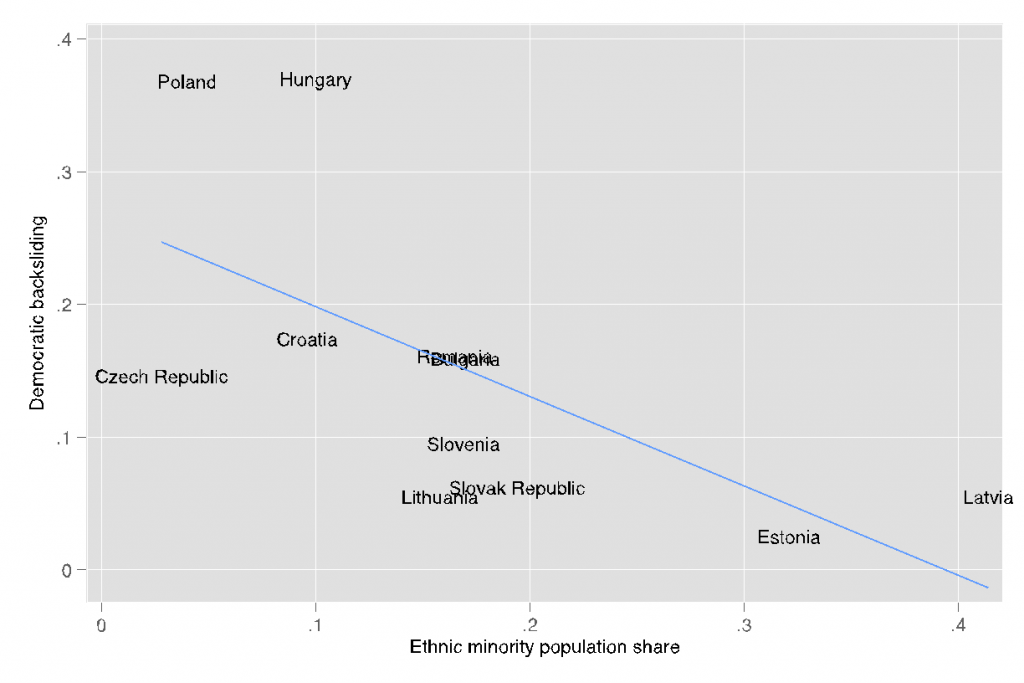

Ethnic Diversity of Eastern European Societies

This research, however, overlooks the observation that democratic backsliding tends to take place in societies that are ethnically more homogeneous — where ethnic minorities are either very small or politically not significant. While some countries in central and eastern Europe, such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland, have few politically organised minorities, other countries in the region, such as Bulgaria, Estonia or Latvia, have important and politically mobilised ethnic groups. Considering the relationship between ethnic heterogeneity and democratic backsliding (figure 1), it is clear that backsliding tends to occur significantly more in homogeneous societies. Why is this the case?

Figure 1: Decline in democracy and ethnic heterogeneity

To answer this question, my research focuses on the interplay between ethnic politics and political competition, and highlights the important positive role played by significant, politically organised ethnic minorities. To the extent that ethnic minorities are permanent minorities — that is, to the extent that they are unable to exit their minority status either by creating an independent polity, or by joining their ethnic kin state — they seek to preserve their group identity in a state they cannot control. In short, permanent minorities seek protection from the tyranny of the majority. The most effective group preservation of permanent minorities is the pursuit of liberal political arrangements that would limit the power of the majority, and grant rights and liberties to individuals and minority groups. Politically organised minority groups thus seek to limit the tyranny of the majority through counter-majoritarian institutions, such as legal oversight of the executive, as well as the preservation of legal equality, individual and group rights, and civil liberties. This political effort on the part of minority representatives bolsters liberal politics and reinforces liberal democracy.

The Positive Role of Ethnic Minorities

This is a novel argument that goes counter to most expectations. Ethnic politics is traditionally seen as a source of nothing but trouble. The extensive literature on ethnic politics has few positive expectations concerning ethnicity and politics. It views ethnicity as a potential source of conflict needing institutional mediation to maintain peaceful relations among groups(5)Lijphart, Arend. 1977. Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration, Yale University Press.; Horowitz, Donald L. 1985. Ethnic groups in conflict., Univ of California Press.. The political impact of unfettered ethnicity is seen as potentially leading to ethnic particularism that undermines collective interests, impairs democracy(6)Akdede, Sacit Hadi. 2010. « Do more ethnically and religiously diverse countries have lower democratization? » Economics Letters ; Barro, Robert J. 1999. « Determinants of democracy. » Journal of Political economy ; Fish, M Steven et Robin S Brooks. 2004. « Does diversity hurt democracy? » Journal of democracy ; Fish, Steven M et Matthew Kroenig. 2006. « Diversity, conflict and democracy: Some evidence from Eurasia and East Europe. » Democratization ; Jensen, Carsten, & Svend-Erik Skaaning. 2012. « Modernization, ethnic fractionalization, and democracy. » Democratization., destabilises polities, prevents effective provision of public goods, and on occasion descends to ethnic conflict and civil war(7)Easterly, William, & Ross Levine. 1997. “Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics; Fearon, James D, & David D Laitin. 1996. “Explaining interethnic cooperation.” American political science review., Cederman, Lars-Erik, Simon Hug, Andreas Schädel, & Julian Wucherpfennig. 2015. “Territorial autonomy in the shadow of conflict: Too little, too late?” , American Political Science Review; Wucherpfennig, Julian, Philipp Hunziker, & Lars-Erik Cederman. 2015. “Who Inherits the State? Colonial Rule and Postcolonial Conflict.” American Journal of Political Science..

My focus is, however, on the role of ethnic politics in the context of relatively stable, peaceful and democratic politics. Departing from the central observation that ethnic minorities are keenly concerned about their self-preservation, I argue that certain political contexts lead them to seek liberal remedies to their minority predicament(8)Kymlicka, Will. 1995. Multicultural Citizenship. Oxford University Press.. This ethnic liberalism is conditional, and can be cross-pressured by various factors. When ethnic minorities face deep ethnic animosity and cannot find any partners among the majority; or when ethnic identity is deeply entrenched in religion which is by definition exclusive, particularistic and conservatising(9)Grzymała-Busse, Anna. 2015. Nations under God: How churches use moral authority to influence policy, Princeton University Press; Gerring, John, Michael Hoffman, et Dominic Zarecki. 2016. « The Diverse Effects of Diverstiy on Democracy. » British Journal of Political Science. or when ethnic groups are too small or too weak to mobilise and successfully contest elections, their liberalism fails. Also, when minorities see a path to exiting their minority status, they may prefer the destabilisation of their polity instead(10)Rovny, Jan, « Circumstantial Liberals: Czech Germans in Interwar Czechoslovakia », LIEPP Working Paper, janvier 2020..

Demonstration for the Autonomy of Székelyföld (Székely Land) © Derzsi Elekes Andor, Budapest, 2013

The presence of politically significant ethnic minorities generally provides an impetus for liberal democracy. Ethnic minority representatives — be they specifically ethnic minority parties, or more general political organisations seeking ethnic support — pursue the reinforcement of civil rights and liberties, strengthening the liberal political pole in the country. The presence of significant ethnic minorities induces the contestation of ethnic issues across the polity(11)Rovny, Jan 2014 “Communism, Federalism, and Ethnic Minorities: Explaining Party Competition Patterns in Eastern Europe”, World Politics., This causes polarisation, mobilising national populist backlash against minorities on the one hand(12)Bustikova, Lenka. 2019. Extreme reactions: Radical right mobilization in eastern Europe, Cambridge University Press.. This alters the political dynamics of heterogeneous societies. While emboldening radical right, it simultaneously reinforces a liberal opposition. In this situation, moderate parties face a wider set of political partners, while parties supporting liberal rights counterbalance the radical right.

Fairly Flexible Partners

Ethnic representatives tend to be good partners. Previous research shows that they tend to have loyal electorates(13)Birnir, Johanna Kristin. 2007. Ethnicity and electoral politics Cambridge University Press. and also tend to be relatively flexible members of governing coalitions. Their focus on civil rights and liberties is offset by relative flexibility on other issues, such as the economy(14)Aha, Katharine. 2019. « Resilient incumbents: Ethnic minority political parties and voter accountability. » Party Politics; Aha, Katharine. 2019. Interethnic Coalitions in Post-Communist Europe, Manuscrit non publié.. They are thus useful collaborators, supporting governments of diverse moderate parties of both the left and the right. When in government, ethnic representatives ensure the maintenance of basic counter-majoritarian principles that are central to democratic functioning.

The presence of politically organised ethnic minorities thus acts as a bulwark against democratic backsliding. Ethnic minority representatives reinforce liberal democracy due to their inherent interest in protecting their group in the face of the majority. Ethnic politics create a national populist backlash, while simultaneously providing a liberal counterbalance.

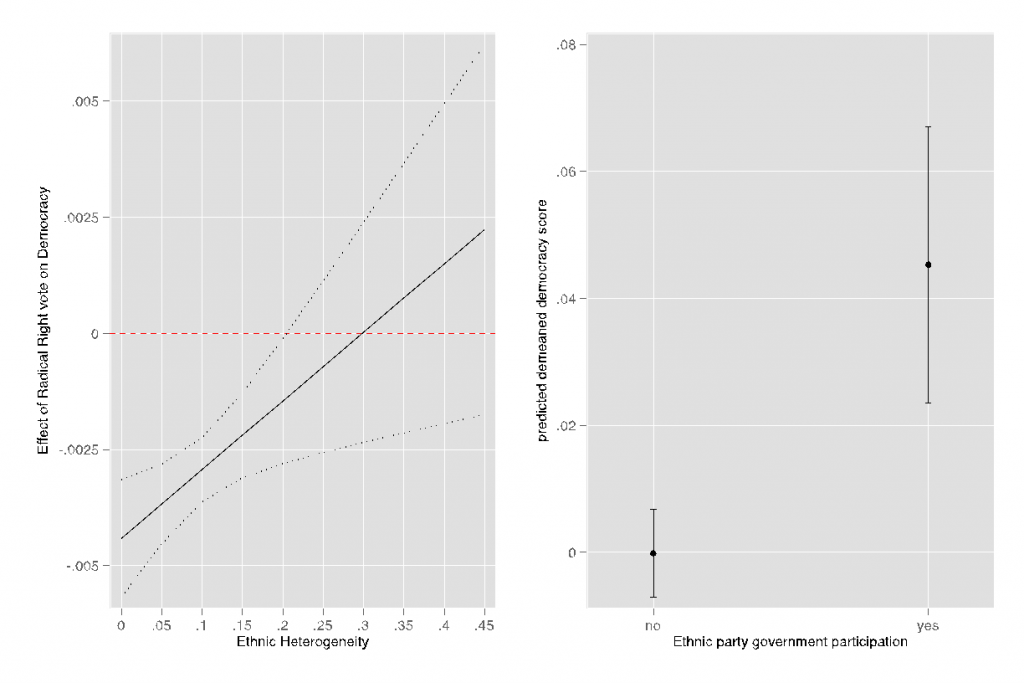

Figure 2: Predicting Democracy

The left panel of figure 2 shows the marginal effect of nationalist populist electoral strength on democracy as ethnic heterogeneity changes. It demonstrates that the electoral strength of the radical right has a strong negative effect on democracy, but only when ethnic heterogeneity is low. As ethnic heterogeneity increases, the corrosive influence of nationalist populists declines towards zero, as organised ethnic representatives provide a counterbalance.

The right panel of figure 2 shows the effect of ethnic minority government participation on democracy, while controlling for GDP per capita, income inequality, unemployment levels, quality of government, and EU membership. It demonstrates that when ethnic minority representatives participate in government, a country’s democracy score (cf. supra) is significantly higher. These dynamics are absent in societies that do not have significant ethnic minorities that can mobilise and influence political competition.

“Poland to the Poles”. Warsaw Independence March 2015. © Piotr Drabik via Flickr

Ethnic politics thus isn’t uniformly harmful. Permanent ethnic minorities have a keen sense of preventing the tyranny of the majority, which is central to democratic functioning. Seeking to limit the majority, ethnic representatives infuse politics with liberal aims. While this emboldens a reaction of the nationalist radical right that is the key driver of democratic decline(15)Palonen, Emilia. 2018. « Performing the nation: the Janus-faced populist foundations of illiberalism in Hungary. » Journal of Contemporary European Studies ; Plattner, Marc F. 2019. « Illiberal Democracy and the Struggle on the Right. » Journal of Democracy ., it simultaneously engenders a liberal opposition. Ethnically heterogeneous countries see the presence of sometimes virulent radical right, but they maintain a liberal political pole underpinned by structured electoral groups in existential need of equality, civil rights, and liberties. It is for this reason that democratic backsliding is most pronounced in countries with small or political unorganised minorities, like Hungary and Poland, while democracy is more resilient in heterogeneous countries with large and politically organised minorities, such as Estonia or Latvia.

Associate Professor, Jan Rovny is a researcher at the Center for European Studies and Compared Politics of Sciences Po (CEE), and at the Interdisciplinary Research Center for the Evaluation of Public Policies (LIEPP). His research concentrates on political competition in Europe with the aim of uncovering the ideological conflict lines in different countries.

Notes

| ↑1 | Vachudova, Milada Anna, 2021 « Populism, Democracy and Party System Change in Europe », Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 24. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Bohle, Dorothee, et Béla Greskovits. 2007. « Neoliberalism, embedded neoliberalism andneocorporatism: Towards transnational capitalism in Central-Eastern Europe. », West European Politics ; Bohle, Dorothee, et Béla Greskovits. 2009. « Varieties of Capitalism and Capitalism tout court. » European Journal of Sociology ; cf. Orenstein, Mitchell Alexander. 2001. Out of the red: building capitalism and democracy in postcommunist Europe, University of Michigan Press. |

| ↑3 | Grzymala-Busse, A., & A. Innes. 2003. « Great expectations: The EU and domestic political competition in East Central Europe. » East European Politics and Societies ; Cianetti, Licia, James Dawson et Sean Hanley. 2018. « Rethinking “democratic backsliding” in Central and Eastern Europe– looking beyond Hungary and Poland. » East European Politics. |

| ↑4 | Bozoki, Andras, & Eszter Simon. 2019. « Two Faces of Hungary » Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989 ; Hanley, Sean, et Milada Anna Vachudova. 2018. « Understanding the illiberal turn: democratic backsliding in the Czech Republic. » East European Politics ; Kreko, Peter, et Zsolt Enyedi. 2018. « Explaining Eastern Europe: Orban’s Laboratory of Illiberalism. » Journal of Democracy ; Sata, Robert, & Ireneusz Pawel Karolewski. 2020. « Caesarean politics in Hungary and Poland. » East European Politics. |

| ↑5 | Lijphart, Arend. 1977. Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration, Yale University Press.; Horowitz, Donald L. 1985. Ethnic groups in conflict., Univ of California Press. |

| ↑6 | Akdede, Sacit Hadi. 2010. « Do more ethnically and religiously diverse countries have lower democratization? » Economics Letters ; Barro, Robert J. 1999. « Determinants of democracy. » Journal of Political economy ; Fish, M Steven et Robin S Brooks. 2004. « Does diversity hurt democracy? » Journal of democracy ; Fish, Steven M et Matthew Kroenig. 2006. « Diversity, conflict and democracy: Some evidence from Eurasia and East Europe. » Democratization ; Jensen, Carsten, & Svend-Erik Skaaning. 2012. « Modernization, ethnic fractionalization, and democracy. » Democratization. |

| ↑7 | Easterly, William, & Ross Levine. 1997. “Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics; Fearon, James D, & David D Laitin. 1996. “Explaining interethnic cooperation.” American political science review., Cederman, Lars-Erik, Simon Hug, Andreas Schädel, & Julian Wucherpfennig. 2015. “Territorial autonomy in the shadow of conflict: Too little, too late?” , American Political Science Review; Wucherpfennig, Julian, Philipp Hunziker, & Lars-Erik Cederman. 2015. “Who Inherits the State? Colonial Rule and Postcolonial Conflict.” American Journal of Political Science. |

| ↑8 | Kymlicka, Will. 1995. Multicultural Citizenship. Oxford University Press. |

| ↑9 | Grzymała-Busse, Anna. 2015. Nations under God: How churches use moral authority to influence policy, Princeton University Press; Gerring, John, Michael Hoffman, et Dominic Zarecki. 2016. « The Diverse Effects of Diverstiy on Democracy. » British Journal of Political Science. |

| ↑10 | Rovny, Jan, « Circumstantial Liberals: Czech Germans in Interwar Czechoslovakia », LIEPP Working Paper, janvier 2020. |

| ↑11 | Rovny, Jan 2014 “Communism, Federalism, and Ethnic Minorities: Explaining Party Competition Patterns in Eastern Europe”, World Politics. |

| ↑12 | Bustikova, Lenka. 2019. Extreme reactions: Radical right mobilization in eastern Europe, Cambridge University Press. |

| ↑13 | Birnir, Johanna Kristin. 2007. Ethnicity and electoral politics Cambridge University Press. |

| ↑14 | Aha, Katharine. 2019. « Resilient incumbents: Ethnic minority political parties and voter accountability. » Party Politics; Aha, Katharine. 2019. Interethnic Coalitions in Post-Communist Europe, Manuscrit non publié. |

| ↑15 | Palonen, Emilia. 2018. « Performing the nation: the Janus-faced populist foundations of illiberalism in Hungary. » Journal of Contemporary European Studies ; Plattner, Marc F. 2019. « Illiberal Democracy and the Struggle on the Right. » Journal of Democracy . |