Migration, Diversity & Mobility

18 November 2020

Influenced Choice: Why Opt for Lockdown?

16 March 2021

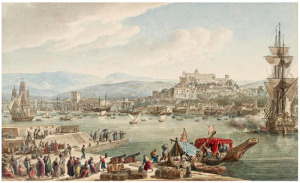

La proclamazione del porto franco di Trieste 18 marzo 1719, painting by Cesare Dell’Acqua (1855)

David Do Paço, Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Centre for History, investigates the production of social relations in situations of strong diversity on local, regional and global scales. His research lies at the intersection between urban history, global microhistory and the new history of international relations. Drawing on the lessons of 18th century history, he attempts to provide solutions to current issues: how can foreigners be integrated in increasingly large, dense and diverse urban societies?

Applying an inter-disciplinary approach, modern history questions the legal frameworks imposed by countries, under which governments form, recognise or deny the existence of a legal community assigned to a religious, linguistic and/or geographic identity. The establishment referred to as a “nation” can thus respond to the desire of a community – often an ethnic or religious minority or a group of foreigners – to guarantee the legal conditions of its existence. This status can also force ethnicised populations to get organised, to regulate themselves and to appoint representatives to associate them with the governing authorities of a city. However, most research remains dependent on a legal bias, which accentuates the community dimension of European cities in the early stages of globalisation. A multitude of players, working outside or between legally recognised communities thus remain in the shadows. Recent research offers new perspectives to allow better identification of how migrations have contributed to the constitution of the first global cities.

Observing the European Cities of the 18th Century

One advantage of the European cities of the 18th century is that they are in the early stages of demographic growth, boosted by both natural increase and strong immigration. This growth results in new socio-professional, religious and linguistic groups, new social areas, and new modes of interaction and sociability, which come up against the structures of the “old regime”. Researchers have focussed on the cities of the southern Mediterranean region because of the volume and quality of the archives remaining, but it is important to point out that these are not specific cases that could support the existence of a unique Mediterranean model. Studies about Strasbourg, Turin and Vienna also reveal social dynamics similar to those observed in Livorno, Trieste, Venice and Smyrna during the same period(1)Hanna Sonkajärvi, Qu’est-ce qu’un étranger ? Frontières et identifications à Strasbourg (1681‑1789), Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg, 2008 ; Simona Cerutti, Étrangers. Étude d’une condition d’incertitude dans une société d’Ancien Régime, Bayard, 2012 ; David Do Paço, L’Orient à Vienne au dix-huitième siècle, Voltaire Foundation, 2015.. More generally speaking, this work calls for the study of global cities throughout the world.

The “Community Cosmopolitanism” Model

A Jewish wedding, Venice, 1780 – Marco Marcola. © Moise Nedja, CC 4.0

The interpretive model dominating the history of migrations in the 18th century is that established by Francesca Trivellato’s study of the Sephardic community of Livorno and its role in the development of the “community cosmopolitanism” of the Tuscan free port from the end of the 18th century(2)Francesca Trivellato, The Familiarity of Strangers. The Sephardic Diaspora, Livorno, and cross-cultural trade in the Early Modern Period, Yale University Press, 2009..

Trivellato demonstrates the Tuscan dukes’ ambitions to interconnect the trade activities of the various merchant communities travelling around the Mediterranean from the end of the 16th century. Each community – Sephardic, Greek, Armenian, etc. – receives privileges enabling it to organise its religious life, use the language(s) of its choice, and administrate itself without restrictions, based on a community legal system within Livorno(3)Trivellato approfondit ici le modèle des port Jews et les travaux de Lois C. Dubin, The Port Jews of Habsburg Trieste. Absolutist Politics and Enlightenment Culture, Stanford University Press, 1999.. Livorno resembles a patchwork of communities, each one being characterised by a high level of internal diversity, such as Jews from different geographic areas, with different languages and cultures, for example. However, this intra-community cosmopolitanism does not mean equal treatment for all. A hierarchy develops, based on the ethnic attribution of the different populations making up Livorno’s Jewish community. This model means that foreigners are not integrated via the city of residence but via one of the families that “represents” their nation. This might be achieved formally through a wedding, patronage or adoption, or more informally for less wealthy immigrants through the protection granted by a family in exchange for services. This is particularly common in Venice, Rome and Vienna.(4)E. Natalie Rothman, ‘Becoming Venetian: Conversion and Transformation in Seventeenth-Century Mediterranean’, Mediterranean Historical Review 21/1 (2006), p. 39-75, Vincenzo Lavenia, Sabina Pavone, Chiara Petrolini, ‘Sacre metamorfosi’. Roma e i racconti di conversione di infedeli e pagani (secoli XVI-XVIII), Roma, Viella, 2020 ; David Do Paço, ‘A case of urban integration: Vienna’s port area and the Ottoman merchants in the eighteenth century’, Urban History (firstview 2020), p. 1-19..

Diversification of Affiliations

This “merchant diaspora” model has been widely publicised and discussed. Today, the very notion of diaspora is sometimes perceived as descriptive. The dynamic nature of the communities and “nations” – used here to describe a group of individuals united by the practice of a minority religion, a set of privileges or even statuses to protect them – is emphasised. Being the receptacle of migrations, the community becomes hierarchically organised, suffers tensions and is regularly required to adjust its balance and mode of operation(5)David Do Paço, ‘La création de la communauté grecque orientale de Trieste par Giuseppe Maria Mainati (1719-1818)’ dans Minorités en Méditerranée au XIXe siècle. Identités, identifications, circulations, Valérie Assan, Bernard Heyberger et Jakob Vogel (ed.), Rennes, PUR, 2019, p. 25-44..

Furthermore, the example of Smyrna (Izmir) shows the limits of the community model and the advantage of working with individuals to escape from its narrow perspective. The recognised members of religious minorities and foreigners may try to integrate different legal communities. They can also get these communities to compete with one another for their own benefit, by asserting their country of origin and citizenship, their religion, or even their family relations and the different groups to which they have access thanks to these relations(6)Marie-Carmen Smyrnélis, Une société hors de soi. Identités et relations sociales à Smyrne aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, Paris, Editions Peeters, 2005.. These multiple affiliations are often expected by political authorities, as is the case in Naples, where the representatives of the French nation first became subjects of the realm(7)Roberto Zaugg, Stranieri di antico regime. Mercanti, giudici e consoli nella Napoli del Settecento, Rome, Viella, 2011..In Trieste, the social standing of immigrants might be improved thanks to the development of the free port, which is accompanied by a rapid diversification of social and legal affiliations. Once their social mobility is sufficiently established, these new families thus form the links between the religious minorities, communities of foreigners, municipal institutions and the local nobility(8)David Do Paço, ‘Una storia adriatica globale nel Settecento: Antonio Rossetti de Scander e il rosolio di Trieste tra Fiume, Venezia e New York’ in Antonio Trampus (ed.), Venezia dopo Venezia. Città-porto, reti commerciali e circolazione delle notizie nel bacino portale veneziano tra Settecento e Novecento (Trieste, Fiume, Pola e l’aera istriano-dalmata), Trieste, IRCI, 2019, p. 27-38.. Such changes bring about the implosion of the community-based interpretation, and enable other approaches to the construction of urban society to be restored.

The Integration of “Day Labourers”

View of the city and port of Trieste from the new pier by Jean-François Cassas. © unknown

Incidentally, it is now becoming evident that the nations cannot absorb all the migrations. This limit on the integration of foreigners into communities is very rapidly observed by the administrative authorities of the free port of Trieste, whose agents repeatedly report that it is impossible to know the exact number of the city’s inhabitants in the 1780s because there is a more or less permanent population that is not sufficiently well off to belong to existing bodies or form new groups.

At the end of the 18th century, local authors thus begin to distinguish the rich families that make up the nation from the anonymous day labourers that are “under the protection” of one nation or another. This population relies upon the confessional solidarity of the free port and the protection of the families that include them in their households, provide dowries for young girls and pay pensions to widows. They can also be integrated* by the administrative authority of the free port, which organises charity by imposing a tax on wine sales for the Casa dei poveri(9)Archivio di Stato di Trieste, c. r. Governo in Trieste, vol. 337 (Wein) et 593 (Städtische Sachen... In exchange, the beneficiaries provide labour for major urban development projects, such as the lazaretto, the commodity exchange or the theatre. Like the merchants, this majority population of poor people, in spite of remaining totally invisible to historiographers, multiply their opportunities to belong to the city’s different bodies in order to benefit from multiple forms of protection.

Muslims: An Invisible and Invisibilised Presence

In this context, the history of Muslims in the European societies of the 18th century is a notable element and their presence has long been as invisible as it is invisibilised by both sources and historians(10)Jocelyn Dakhlia, “Introduction. Les musulmans en Europe occidentale au Moyen Âge et à l’époque moderne : une présence invisible” dans Jocelyne Dakhlia et Bernard Vincent (dir.), Les musulmans dans l’histoire de l’Europe. Vol 1: une intégration invisible, Paris, Albin Michel, 2011.. Her research enables reinterpretation of a large part of the social history of Europe. Apart from Venice, which recognises the Muslim population in its territory in 1575, Messine, who occasionally taxes the port’s Muslims (also applying the same tax to Jews), and Vienna, which recognises the existence of a Muslim population in 1767 without establishing it as a community, Muslims are not recognised politically. The study of this population is a methodological challenge that implies starting with the individual rather than a given category in order to re-create the social spheres(11)David Do Paço, ‘Muslims in Christian-ruled Europe, 15th-19th c.’ in The Routledge Handbook of Islam in the West, Londres, Routledge, forthoming..

The importance of developing urban microhistory

A preliminary study of Muslims living in Vienna and Trieste enables presentation of a first set of conclusions. In the territories administered by the House of Habsburg, there is a Muslim population comprising men and women of several generations, of various origins (Anatolia, Bosnia, North Africa), with different social and professional statuses, generally, but not always, arriving of their own free will. This population never constitutes a relational community and is not concentrated geographically. It appears to be organised on the basis of family ties, although these are not exclusive.

Today, the diffuse nature of the presence of Muslims in the regions and the strata of the Austrian society of the 18th century suggests more diversified urban societies than were suspected both in the Mediterranean region and in central Europe. The social factory of cities can be organised around a number of different spaces: buildings, streets, districts, eating houses or work places, which are not part of the community organisation of the society.

A population that is invisible in the administrative sources is not necessarily absent from the public space of a city. Here, integration must be considered in terms of both the vertical solidarity developed by the foreigners and the self-serving forms of protection that they receive, notably from the families that represent the basic social unit of the 18th century. Finally, this history of immigration and social integration invites the development of a connected urban history to ascertain the integration of social spaces in different cities and regional areas(12)David Do Paço, ‘Islam and Muslims in the Habsburg Monarchy’ in The Cambridge History of the Habsburg Monarchy, Howard Louthan and Graeme Murdock (dir.), Cambridge, CUP, forthoming. .

David Do Paço is an Assistant Professor of 18th century history at the Sciences Po Centre for History. His research lies at the intersection between urban history, global microhistory and the new history of international relations. He investigates the production of social relations in situations of strong diversity on local, regional and global scales. See hie publications.

Notes

| ↑1 | Hanna Sonkajärvi, Qu’est-ce qu’un étranger ? Frontières et identifications à Strasbourg (1681‑1789), Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg, 2008 ; Simona Cerutti, Étrangers. Étude d’une condition d’incertitude dans une société d’Ancien Régime, Bayard, 2012 ; David Do Paço, L’Orient à Vienne au dix-huitième siècle, Voltaire Foundation, 2015. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Francesca Trivellato, The Familiarity of Strangers. The Sephardic Diaspora, Livorno, and cross-cultural trade in the Early Modern Period, Yale University Press, 2009. |

| ↑3 | Trivellato approfondit ici le modèle des port Jews et les travaux de Lois C. Dubin, The Port Jews of Habsburg Trieste. Absolutist Politics and Enlightenment Culture, Stanford University Press, 1999. |

| ↑4 | E. Natalie Rothman, ‘Becoming Venetian: Conversion and Transformation in Seventeenth-Century Mediterranean’, Mediterranean Historical Review 21/1 (2006), p. 39-75, Vincenzo Lavenia, Sabina Pavone, Chiara Petrolini, ‘Sacre metamorfosi’. Roma e i racconti di conversione di infedeli e pagani (secoli XVI-XVIII), Roma, Viella, 2020 ; David Do Paço, ‘A case of urban integration: Vienna’s port area and the Ottoman merchants in the eighteenth century’, Urban History (firstview 2020), p. 1-19. |

| ↑5 | David Do Paço, ‘La création de la communauté grecque orientale de Trieste par Giuseppe Maria Mainati (1719-1818)’ dans Minorités en Méditerranée au XIXe siècle. Identités, identifications, circulations, Valérie Assan, Bernard Heyberger et Jakob Vogel (ed.), Rennes, PUR, 2019, p. 25-44. |

| ↑6 | Marie-Carmen Smyrnélis, Une société hors de soi. Identités et relations sociales à Smyrne aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles, Paris, Editions Peeters, 2005. |

| ↑7 | Roberto Zaugg, Stranieri di antico regime. Mercanti, giudici e consoli nella Napoli del Settecento, Rome, Viella, 2011. |

| ↑8 | David Do Paço, ‘Una storia adriatica globale nel Settecento: Antonio Rossetti de Scander e il rosolio di Trieste tra Fiume, Venezia e New York’ in Antonio Trampus (ed.), Venezia dopo Venezia. Città-porto, reti commerciali e circolazione delle notizie nel bacino portale veneziano tra Settecento e Novecento (Trieste, Fiume, Pola e l’aera istriano-dalmata), Trieste, IRCI, 2019, p. 27-38. |

| ↑9 | Archivio di Stato di Trieste, c. r. Governo in Trieste, vol. 337 (Wein) et 593 (Städtische Sachen. |

| ↑10 | Jocelyn Dakhlia, “Introduction. Les musulmans en Europe occidentale au Moyen Âge et à l’époque moderne : une présence invisible” dans Jocelyne Dakhlia et Bernard Vincent (dir.), Les musulmans dans l’histoire de l’Europe. Vol 1: une intégration invisible, Paris, Albin Michel, 2011. |

| ↑11 | David Do Paço, ‘Muslims in Christian-ruled Europe, 15th-19th c.’ in The Routledge Handbook of Islam in the West, Londres, Routledge, forthoming. |

| ↑12 | David Do Paço, ‘Islam and Muslims in the Habsburg Monarchy’ in The Cambridge History of the Habsburg Monarchy, Howard Louthan and Graeme Murdock (dir.), Cambridge, CUP, forthoming. |