Unlocking Migration Politics: Gaps and Biases in Scientific Debates

16 November 2020

Migration, Wages and (un)Employment

16 November 2020

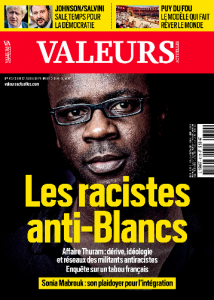

Cover of « Valeurs Actuelles », a French weekly newspaper, 12 September 2019

Given that the denunciation of “anti-White racism” has become one of the far right’s hobbyhorses in France, the temptation is great to see it as an oxymoron – as nothing but “nonsense” (1)Danièle Obono et la valeur actuelle du racisme, Tribune of a collective of academics including notably the historian Ludivine Bantigny and the sociologists Sarah Mazouz and Ugo Palheta ; Le racisme anti-Blancs existe-t-il ?, France Culture, October 2018 with Éric Fassin, sociologist.and an “intellectual imposture” (2)Repères contre le racisme, pour la diversité et la solidarité internationale, intervention by sociologist Stéphane Beaud and historian Gérard Noiriel, conference “Under the masks of” anti-white racism “, February 9, 2013.– sometimes based on a confusion between racism and discrimination(3)De l’urgence d’en finir avec « le racisme anti-blanc », intervention de Joao Gabriel, 8 septembre 2019..

While understandable, this temptation is problematic.

To see this, one need only go over the three main conceptions of racism currently used in all the relevant disciplines: anthropology, law, history, philosophy, psychology, political science, and sociology.

Ideological Racism

First, racism can be defined as an ideology consisting of a set of propositions: 1) Humanity is composed of groups that are essentially distinct from one another and characterised by intrinsic properties that are either natural or cultural; 2) These distinctive properties are innate, immutable, and hereditary; 3) They determine a certain number of traits, aptitudes, and behaviors that may be comparatively assessed; 4) This evaluation leads to the establishment of a hierarchy between those (the so-called “races”); 5) This hierarchy justifies the domination of inferior races by superior ones.

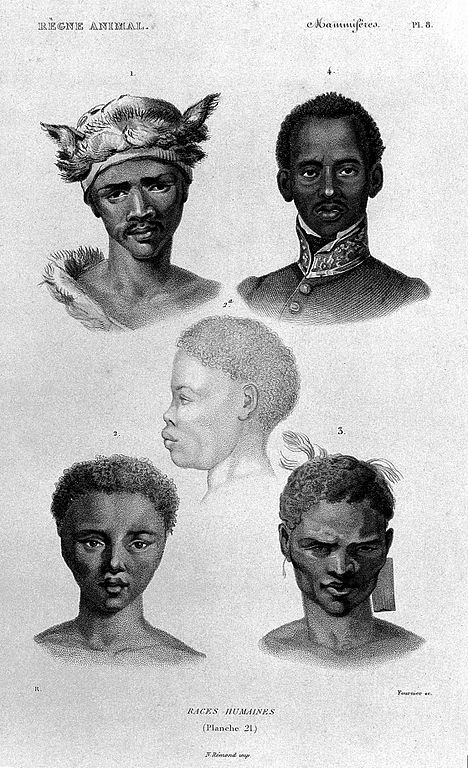

G.F. Cuvier: racial characteristics; 1836-49

This conception of racism as an ideology, which appeared in the inter-war period, is by no means obsolete. It is shared by authors as diverse – and as renowned – as the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss(4)Claude Lévi-Strauss, Didier Eribon, De près et de loin, Odile Jacob, 1988, the American-Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah(5)Kwame Anthony Appiah, In My Father’s House, Oxford University Press, 1992., and the sociologists Robert Miles (British)(6) Robert Miles, Racism, Routledge, 1989. and William Julius Wilson (American)(7)William Julius Wilson, The Bridge over the Racial Divide. Rising Inequality and Coalition Politics, University of California Press, 1999.. From this perspective, since the beliefs listed above are erroneous, a proper anti-racist strategy should involve disseminating accurate information conducive to the revision and, ultimately, the abandonment of these false beliefs. “Racialised” groups are those unduly cast as “races” in the aforementioned sense of the term and mistreated as such(8)Lawrence Blum, « Racialized Groups : The Sociohistorical Consensus », The Monist, 93 (2), 2010, p. 298-320 ; Michael Hardimon, Rethinking Race. The Case for Deflationary Realism, Harvard University Press, 2017.. Their members cannot entirely escape the mental burden of anticipating and protecting themselves from potentially negative responses to their stigmatised traits. Conversely, “being white means not having to think about it”(9)Robert Terry, « The Negative Impact on White Values », dans Benjamin Bowser et Raymond Hunt (eds), Impacts of Racism on White Americans, Sage, 1981, p. 120.. This is arguably the quintessence of the “privilege” inevitably associated with that position in the racial hierarchy.

Attitudinal Racism

According to another line of thinking that appeared a few decades later and is mostly based on social psychology, racism can also be defined as a range of negative attitudes determined by the targeted individual’s perceived membership in a group conventionally defined as “racial”. These predominantly affective – rather than cognitive(10)Jorge Garcia, « Le cœur du racisme », dans Magali Bessone et Daniel Sabbagh (dir.), Race, racisme, discriminations. Une anthologie de textes fondamentaux, Hermann, coll. « L’Avocat du Diable », 2015, p. 125-155. – mental states include hatred, some less intense kinds of animosity, fear, disgust, contempt, disrespect(11)Joshua Glasgow, « Racism as Disrespect », Ethics, 120 (1), 2009, p. 64-93., and simple indifference to the wellbeing and legitimate interests of the individual involved. They can rightly be described as racist even if the person who harbours them does not embrace racism as a doctrine.

© Shutterstock

These attitudes, which largely result from socialisation, may vary over time, and are not immediately observable: they can only be inferred from observed behavior. However, they do not necessarily translate into perceivable acts. It is entirely possible that a racist attitude does not result in any discrimination, either because the person experiencing it disapproves of it and manages to prevent it from coming into play, or because s/he is seeking to avoid the opprobrium that would meet the exteriorisation of racist affects in certain contexts, or because s/he fears legal repercussions.

From this perspective, in accordance with Gordon Allport’s hypothesis in his pioneering 1954 book(12)Gordon Allport, The Nature of Prejudice, New York, Basic Books, 1979 [1954]., an adequate anti-racist strategy should promote increased interactions between members of different racial groups placed on an equal footing (1) and required to cooperate (2) to achieve a common goal (3), with the support of some acknowledged authority (4). Indeed, for more than half a century, a large number of experimental studies have shown that such interactions do result in lowering the emotional component of racism. Moreover, this decrease is a lasting one. Finally, it benefits all members of the stigmatised group – beyond the individuals involved in the interaction – as well as members of other similar minorities(13)Thomas Pettigrew et Linda Tropp, « A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory », Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90 (5), 2006, p. 751-783..

Systemic Racism

“March of Silence”, Seattle, Washington / USA – June 12 2020 © 2003-2020 Shutterstock

The third and most recent conception of racism casts it as a system comprising all the factors (ideas, discourse, actions, institutional rules…) that contribute to the production and reproduction of inequalities between “racial” groups(14)Stokely Carmichael et Charles Hamilton, Black Power. The Politics of Liberation in America, New York, Vintage, 1967 ; Robert Blauner, Racial Oppression in America, New York, Harper and Row, 1972.. Each of these causal elements would then qualify as “racist” for this reason alone. Although it is now popular on both sides of the Atlantic, this conception of “systemic” racism raises at least three issues.

Analytically, it does not allow one to distinguish the specific mechanisms (physical violence, discrimination, segregation, stigmatisation, self-disqualification…) whose interaction generates and perpetuates the disadvantages experienced by members of racialised groups (15)Glenn Loury, « Les stéréotypes raciaux », dans Bessone et Sabbagh, Race, racisme, discriminations, op. cit., p. 203-234 ; Elizabeth Anderson, « Ségrégation, stigmatisation raciale et discrimination », ibid., p. 235-276.. Yet only a careful examination of their interconnections, based on such prior distinctions, would enable the development of appropriate public policies.

Politically, on the one hand, “systemic racism” risks weakening the anti-racist coalition by alienating the goodwill of potential members, who may be discouraged by seeing their own behavior fall under this most extensive, morally loaded, and strongly accusatory label. On the other hand, conversely, it risks trivialising well-founded accusations of racism in the narrower sense: if everything is “racist”, then ultimately, nothing is.

What About “Anti-White racism”?

Following this brief overview, let us return to our initial question: does “anti-White racism” exist?

Elijah Muhammad standing behind microphones at podium / World Telegram & Sun photo by Stanley Wolfson, via Wikimedia Commons

If “racism” is understood as the ideology or negative attitudes mentioned above, given the extent and intensity of the racism suffered by “non-Whites”, it would be surprising, to say the least, if there were no instance – be it only reactive – of “anti-White racism”. In fact, it is not very difficult to find some. An “ideological” example would be the statement by Elijah Muhammad, the president of the American organisation Nation of Islam from 1934 to 1975, that all Whites are like “demons”. An “attitudinal” example in France is the video that rapper Nick Conrad posted online in September 2018 entitled “Hang the Whites”, which resulted in a 5,000 euro fine for incitatement to commit a crime. In both cases, the phrase “anti-White racism” does not seem to be a misnomer.

Needless to say, none of the above supports the aberrant thesis that, in France or elsewhere, the extent of “anti-White racism” comes close to the extent of the racism that minorities face. The arguments formulated here do not entail of any such equivalence. Clearly, racial discrimination – be it direct or indirect, intentional or unintentional, or even “systemic” – does not equally harm Whites and non-Whites.

Yet it is only if one opts for the third – “systemic” – conception of racism and if one entirely excludes the two others that “anti-White racism” becomes an oxymoron . But why should this option be favored over a pluralistic approach? Racism is a multidimensional phenomenon. To argue that “anti-White racism does not exist” requires the complete elimination of two of its main dimensions. The end does not justify the means. Rather than providing the far right with the bonanza of a “taboo” to be exploited for its own benefit, it would be preferable to address the existence of an “anti-White racism” as an empirical issue rather than as conceptual impossibility. In all likelihood, this will help take the wind out of its sails(16)This text benefited from critical remarks by Laure Bereni, Magali Bessone, Julie Saada and Hélène Naudet, whom I thank..

Daniel Sabbagh's work focuses on discrimination and affirmative action (from a comparative and multidisciplinary perspective), multiculturalism, American law, theories of justice and equality, the internal determinants of American foreign policy, and the death penalty in the United States. See his publications.

Notes

| ↑1 | Danièle Obono et la valeur actuelle du racisme, Tribune of a collective of academics including notably the historian Ludivine Bantigny and the sociologists Sarah Mazouz and Ugo Palheta ; Le racisme anti-Blancs existe-t-il ?, France Culture, October 2018 with Éric Fassin, sociologist. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Repères contre le racisme, pour la diversité et la solidarité internationale, intervention by sociologist Stéphane Beaud and historian Gérard Noiriel, conference “Under the masks of” anti-white racism “, February 9, 2013. |

| ↑3 | De l’urgence d’en finir avec « le racisme anti-blanc », intervention de Joao Gabriel, 8 septembre 2019. |

| ↑4 | Claude Lévi-Strauss, Didier Eribon, De près et de loin, Odile Jacob, 1988 |

| ↑5 | Kwame Anthony Appiah, In My Father’s House, Oxford University Press, 1992. |

| ↑6 | Robert Miles, Racism, Routledge, 1989. |

| ↑7 | William Julius Wilson, The Bridge over the Racial Divide. Rising Inequality and Coalition Politics, University of California Press, 1999. |

| ↑8 | Lawrence Blum, « Racialized Groups : The Sociohistorical Consensus », The Monist, 93 (2), 2010, p. 298-320 ; Michael Hardimon, Rethinking Race. The Case for Deflationary Realism, Harvard University Press, 2017. |

| ↑9 | Robert Terry, « The Negative Impact on White Values », dans Benjamin Bowser et Raymond Hunt (eds), Impacts of Racism on White Americans, Sage, 1981, p. 120. |

| ↑10 | Jorge Garcia, « Le cœur du racisme », dans Magali Bessone et Daniel Sabbagh (dir.), Race, racisme, discriminations. Une anthologie de textes fondamentaux, Hermann, coll. « L’Avocat du Diable », 2015, p. 125-155. |

| ↑11 | Joshua Glasgow, « Racism as Disrespect », Ethics, 120 (1), 2009, p. 64-93. |

| ↑12 | Gordon Allport, The Nature of Prejudice, New York, Basic Books, 1979 [1954]. |

| ↑13 | Thomas Pettigrew et Linda Tropp, « A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory », Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90 (5), 2006, p. 751-783. |

| ↑14 | Stokely Carmichael et Charles Hamilton, Black Power. The Politics of Liberation in America, New York, Vintage, 1967 ; Robert Blauner, Racial Oppression in America, New York, Harper and Row, 1972. |

| ↑15 | Glenn Loury, « Les stéréotypes raciaux », dans Bessone et Sabbagh, Race, racisme, discriminations, op. cit., p. 203-234 ; Elizabeth Anderson, « Ségrégation, stigmatisation raciale et discrimination », ibid., p. 235-276. |

| ↑16 | This text benefited from critical remarks by Laure Bereni, Magali Bessone, Julie Saada and Hélène Naudet, whom I thank. |