Defending Humanity by Protecting its Heritage

16 March 2021

Counting the Forgotten in Politics

16 March 2021 Like mechanization in the 19th century, innovation – and especially digital innovation – is often considered to be a job destroyer. This is not the case, as Céline Antonin, Philippe Aghion, and Simon Bunel show in their book The power of creative destruction (Le pouvoir de la destruction créatrice, Odile Jacob, October 2020). Drawing on the most recent empirical work, the authors revisit several theories and enigmas of economic history through the prism of creative destruction – an idea that the economist Joseph Schumpeter put forward in the mid-20th century. In particular, they study innovation and growth, development, taxation, industrial policy, and the environment. Céline Antonin explains

Like mechanization in the 19th century, innovation – and especially digital innovation – is often considered to be a job destroyer. This is not the case, as Céline Antonin, Philippe Aghion, and Simon Bunel show in their book The power of creative destruction (Le pouvoir de la destruction créatrice, Odile Jacob, October 2020). Drawing on the most recent empirical work, the authors revisit several theories and enigmas of economic history through the prism of creative destruction – an idea that the economist Joseph Schumpeter put forward in the mid-20th century. In particular, they study innovation and growth, development, taxation, industrial policy, and the environment. Céline Antonin explains

Your book aims to update the renowned theory of creative destruction that Joseph Schumpeter developed in the mid-20th century. Why this project?

This book is much more than an update. Joseph Schumpeter originally formulated the principle of creative destruction based on his intuitions, but without really building a theory or an empirical body.

In this book, we scientifically validate the principle of creative destruction by showing that “cumulative innovation” is the main driver of prosperity. We also show that this principle is at the heart of the economy and allows us to solve and think about several puzzles and paradoxes in economic history, ranging from development to globalisation, and from inequalities to the environment. We thus offer keys to understanding the origins of growth, and propose a reform of capitalism.

Joseph A. Schumpete. 1943/Harvard University Archives. © CC BY NC ND 3.0

Moreover, our conclusions differ from the pessimistic ones of Schumpeter, who believed that creative destruction would inevitably lead to an impasse. He argued that once innovators became heads of powerful conglomerates, they would block new innovations in order to preserve their vested interests. We are more optimistic, however. We believe that it is possible to overcome this impasse with the intervention of the market – State – civil society triad.

In his book, Schumpeter argued that innovation does not cause mass unemployment. This is an against-the-grain perspective. Were you able to confirm this “intuition”?

Great industrial revolutions have historically not caused mass unemployment. It is important to bear in mind that innovation has two effects on employment: a displacement effect, which involves the destruction of some existing tasks, and a productivity effect, which leads to an increase in market power, and therefore the creation of new jobs. These two antagonistic effects must therefore be added together to determine the impact of innovation on employment.

To empirically test this impact, we looked at the link between employment and automation in a broad sense, based on data from companies in the French industrial sector between 1994 and 2015. Our conclusion is very clear: automation has a positive impact on employment, and increasingly so over time, for both skilled and unskilled jobs. In other words, automation creates more jobs in factories and industrial companies than it destroys. We are not the only researchers who have highlighted this finding: several studies conducted in other countries (United States, United Kingdom, Spain, Canada…) have reached the same conclusions.

Can the jobs created by innovation be considered an ideal substitute for the jobs they destroy?

The first question is to determine what jobs are most likely to be destroyed. Since the early 2000s, the general wisdom has been that routine tasks subject to automation would gradually disappear and be overtaken by machines.

Home delivery service across the UK from thebar.com and Deliveroo. © TaylorHerring via Flickr. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

At the same time, automation would create greater demand for non-routine jobs requiring skills and qualifications. Empirical evidence shows that automation has created more high-skilled and low-skilled jobs, but squeezed medium-skilled routine jobs. Thus, there is a legitimate fear of a race to the bottom, with medium-skilled workers slipping into low-skilled and precarious jobs, such as those created by digital platforms (gig economy).

How to avoid this negative spiral? The disappearance of routine tasks does not necessarily imply the disappearance of jobs; in many cases, it actually involves a transformation of jobs into non-routine ones. In banking, the advent of chatbots can free customer service representatives from some of their activity answering routine questions with low added value. Freed from this task, they could focus on more complex and personalized tasks, devote more time to new, tailored customer services, or move into the wealth advisor profession.

The key to a move towards more high-skill jobs firmly lies in initial and continuing education. With regard to initial training, enabling new generations to fill future jobs involves anticipating the future needs of the economy, particularly by focusing on digital tools and data science. In addition, a real policy of lifelong professional training would allow everyone to become more skilled.

You point to the fact that innovations take time to become established and generate growth. What are the most telling examples of this? What process links innovation and growth?

A significant time lag exists between inventions and the takeoff in growth. To understand this lag in the dissemination of innovation, let us return to the fundamental innovations that produce “generic technology”. Three properties characterise them and explain the time lag between their invention and the takeoff in growth: the importance of secondary innovations, the time lag in the dissemination within firms, and the time lag for household adoption. Our book goes over each of these characteristics in detail. These characteristics help explain the gap between the moment when generic innovation occurs and the moment when an actual increase in economic growth is observed.

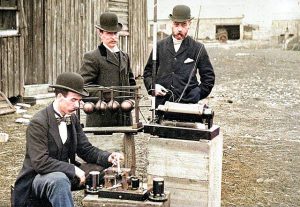

British Post Office engineers inspect Guglielmo Marconi’s wireless telegraphy equipment, May 1897. © CC BY 3.0

The examples we present in our book include the one developed by Paul David that illustrates the slow adoption of electricity by manufacturers. Despite the introduction of electricity in 1899, factories remained organized according to a “group drive” system of power transmission that had remained unchanged since the days when factories were powered by water mills. The force of the water turned a driveshaft, to which each machine was connected. As the industrial revolutions progressed, steam replaced water as the source of energy in the factories, and then the electric motor replaced steam, but without changing the overall organisation. A major disadvantage of the driveshaft system was that similar machines had to be placed next to each other in a layout that was not optimal for the production line. In the early 1910s, Henry Ford noticed that electricity could do two things that steam could not: transport energy through wires and shrink engines. These two secondary innovations changed everything: the driveshaft could be eliminated, enabling the invention of the assembly line, which increased plant productivity tenfold.

Can similar approaches be used to analyse industrial and service innovations, especially those created by digital technology?

Yes, because even if digital innovations seem to be revolutionising the organisation of activities more than industrial innovations, the three aforementioned characteristics of generic innovations also apply to digital innovations. As we show in the book, the disseminations of electricity and of ICTs to households have followed almost identical trajectories since their introduction. Moreover, Paul David draws parallels between the misuse of electricity at the end of the 19th century and the misuse of computers at the end of the 20th century. While computers should have enabled the digitisation of many data processing tasks from the outset, he notes that longstanding hardcopy processes were maintained, leading to a duplication of tasks and low productivity growth at the end of the 1980s.

You argue for reindustrialisation, which seems to conflict with environmental imperatives, particularly in terms of the exploitation of natural resources and pollution. Can innovation resolve this paradox?

Share of industry in the Gross Domestic Product compared between China, Germany, the United States and France. © World Bank

The Covid-19 crisis has highlighted the deindustrialisation of France in several strategic sectors: the pharmaceutical, automotive, and electronic industries… Our manufacturing sector now only accounts for 10% of GDP, versus 20% in Germany. Yet manufacturing is an engine of growth, employment, and innovation, and an element of power. We need to turn the tide.

Furthermore, this reindustrialisation is not incompatible with environmental goals, thanks to innovation. It is important to note that innovation is not necessarily environmentally friendly: companies that have produced and innovated in polluting technologies in the past – for example, in internal combustion engines – would rather continue innovating in these polluting technologies. It is therefore the State’s responsibility to intervene and redirect corporate innovation towards green technologies. Not that the State should supplant companies. Rather, it should shape the incentives, through measures such as domestic and border adjustable carbon taxes, funding for “clean” innovation, etc. We develop the idea that civil society also has an important role to play in encouraging companies to innovate in green technologies.

You take a comparative approach to the United States and Europe in particular. What are the advantages and shortcomings of each model?

The United States embraces a model of capitalism that promotes innovation but does not protect individuals from either macroeconomic shocks or individual risks of job loss. The Covid-19 crisis led to massive job destruction in the United States, yet healthcare insurance and individual income are both tightly linked to employment. As a result, the share of the U.S. population without healthcare insurance and at risk of falling into poverty has increased sharply during this crisis. By contrast, Western Europe has a much more protective but less innovative form of capitalism than in the United States.

Obamacare publicity, Chicago, Illinois, 2017. © Heather A Phillips / Shutterstock.com

Does this mean that Europe has to give up on social protection if it wants to become more innovative? We show that this is not the case. In the 1990s in particular, Scandinavian countries implemented structural reforms to stimulate innovation by lowering capital taxes, adopting flexicurity, etc. These reforms promoted innovation without challenging the social model. For example, flexicurity allows people who have lost their job to receive 90% of their former salary for two years while receiving training to reskill for a new job. Training policy is of paramount importance here, and a prerequisite for successful flexicurity.

One of your objectives is to create pathways to reform capitalism, especially with regard to competition regulation and taxation, to address Big Tech’s GAFAs. What would be the right approach?

Sept. 23th 2019 : Handprints on the Wall in Amazon logistics at Vélizy Villacoublay in France. © Frederic Legrand – COMEO / Shutterstock

Antitrust policy was developed before the emergence of the GAFAs and needs to be rethought. Its main pitfall is that it is often considered in a static way, by focusing on the market structure at a given moment t. However, the process of creative destruction involves the constant creation of new markets to replace existing ones. The intensity of the competition should be measured less by the number of firms than by the number of entries and exits over time.

What can be done concretely to remedy this?

Like Richard Gilbert (2020), we believe that it is not necessary to rewrite antitrust law, but that its use should be adapted to foster “dynamic competition”, that is, innovation, the entry of new companies, and the creation of new markets. In particular, antitrust authorities should no longer use the definition of existing markets as their main guidepost. Furthermore, when analysing the costs and benefits of a merger or acquisition, its anticipated effects on innovation and the creation of future markets should be integrated into the analysis.

Do you believe civil society should play a role in this reform of capitalism? What could it concretely do??

We emphasise the importance of the State – business – civil society triad in making the innovation economy work. Civil society – the media, intermediary bodies, and associations – generates constitutional levers that can harness executive power and ensure greater efficiency and justice in market operations. The mobilisation of civil society has historically heavily shaped the evolution of capitalism towards a system that is better regulated, more inclusive and protective, and more environmentally conscious. Our book uses several historical examples to show how civil society has enlivened democracy. Concrete means of action vary. First, legal action could be taken via the Constitutional Council or appeals to the European Court of Human Rights. Other forms of action could include citizen movements, media mobilisation, and new opportunities created by social networks.

Céline Antonin is a researcher at OFCE, research center in economics of Sciences Po, a lecturer at Sciences Po, and a research associate at the Collège de France. Her research focuses on innovation and the digital economy, savings and heritage, the oil economy, and the euro zone (Germany, Italy, Greece). See her publications Philippe Aghion is a professor at the Collège de France and the London School of Economics, and a member of the Econometric Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His research mainly focuses on growth theory and the economics of innovation. He has received many prestigious awards for his research. Simon Bunel is a doctoral student in economics at the Paris School of Economics. He is also an economist at the Banque de France and INSEE. He is an associate researcher at the Collège de France (Innovation Lab) and focuses on technological innovation and change and work.