Fact-checking: between beliefs and knowledge, a tough fight to win

6 May 2019

The Political Consequences of Technological Change

6 May 2019par Dominique Cardon, Jean-Philippe Cointet, Benjamin Ooghe-Tabanou, Guillaume Plique, médialab

Bruno Patino, Jean-François Fogel, School of journalism

This article draws on a survey conducted by the medialab with Sciences Po’s School of Journalism for the Montaigne Institute.

Boston, 07/09/2009. A participant in a Labor Day protest in the Boston Common supporting national healthcare reform holding a sign reading “Fox is not News” © Right Coast Images, Shutterstock

Circulations of fake news, bombardments of messages produced by robots, dispensaries targeting web users, Russian influence networks, etc. At a time of many concerns about the authenticity of public debate, it is worth considering the structure of digital information production and circuits. These disturbances are often interpreted as the consequence of information market deregulation (Bronner, 2013). Short-circuited by social networks open to all types of speech producers, traditional media have lost the control they had over shaping public opinion. The “digital” public has become treacherous, uncontrollable, and easily manipulated.

A 3-staged digital public space

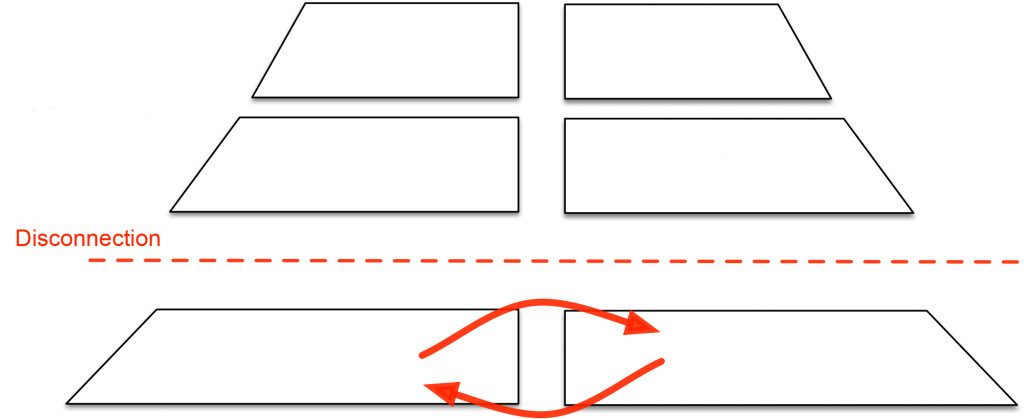

While many comments attribute an almost quasi-direct responsibility to these phenomena in some contemporary political events (Brexit, the elections of Donald Trump or of Jair Bolsonaro), recent research results call for more circumspection. In the United States, for example, even though a significant amount of “fake news” circulated during the 2016 presidential election, the information was mainly disseminated to an audience of activists who were already convinced (Grinberg et al., 2019; Guess, Nyhan, Reifler, 2016), and the rare studies on the effects on users fall short of measuring its impact (Allport, Gentzkow, 2017). Rather than approach the issue of fake news in an isolated manner, it makes sense to reposition it within the overarching architecture of the digital information space. The latter is not an even surface that equally exposes everyone to all possible sources of information. The production of information, its visibility, and the way it lives in different parts of the web, depend on the way journalists, politicians, and new voices arising across the web build and specifically shape information circuits. It is thus possible to show at a macroscopic level that digital information circulation paths are closely connected to the properties of various national media and political spaces. Three strata of this overarching architecture can be schematically isolated: the authority of information from websites, the influence resulting from the circulation of this information, especially on Twitter, and the conversation, particularly on Facebook, which, in a more fragmented and covert way, is developing in the relational niches that users create (Fig 1.).

In this very simple diagram, it is possible to identify two dynamics creating tension in the structure of digital public space: a polarisation process and what we call a disconnection process. This distinction shows how the overall structure of the media-political system constitutes a system of forces and constraints that enables the emergence of different information circuits depending on the strategies of actors and the consistency of political and professional constraints in the public space. This difference is particularly obvious when comparing research on the United States and France.

American polarization

Trump tweet on 01/12/2016 “@MajorCBS’s Major Garrett of @CBSNews covers me very inaccurately…total agenda, bad reporter!”

In the aftermath of the election of Donald Trump, an ideological polarization process in the media space has become apparent in America. The disinformation produced on extremist sites with poor visibility – i.e. with little authority and with an influence limited to small parts of social networks – is regularly picked up by media with great visibility and strong authority in the mainstream media space (Benkler et al., 20018). With the dominance of Fox News and of Breitbart as media leaders in Republican circles and the assumption of power by Donald Trump, equipped with his Twitter account, it is from the center of the public space that actors with great authority have sought to “launder” the questionable information produced by disinformation websites with low visibility. From top to bottom of the digital space, a propaganda feedback loop has appeared (Benkler et al., 2018) and contributed to dividing the American media space and creating a different space – that of alternative facts. This polarization of the American media system results from a broad and deep political strategy involving political and media actors with many resources and highly significant visibility. It is necessary to have positions of authority to establish the existence, in a polemic way, of the idea of an “alternative world” wherein facts deemed fake by most mainstream media are actually “true”. This global transformation of the American media landscape, following the alt-right takeover of Fox News, played a key role in shaping the media agenda during the 2016 election, leading the New York Times to in turn more frequently feature Hillary Clinton’s email scandal on its front page than the candidate’s platform (Watts & Rothschild, 2017).

The French disconnection

This process is not apparent in the French case, although many tensions appeared in the mainstream media space with the introduction of new actors and new ways of promoting factually suspect information. The media at the center of the public space quote each other, but in solidarity do not (or barely) quote questionable information produced by counter-information websites (Gaumont et al., 2018). Even if Twitter shares, especially from the far right, can make fake news influential, in the French situation mainstream media generally resist misinformation from the counter-informational sphere. This solidarity in the French media landscape is characterized by journalists’ high level of caution on the reliability of information and their use of fact-checking mechanisms – as attested by the CheckNews initiative, which gathered the editors of various French newspapers during the 2017 presidential and legislative elections.

La Ligue du LOL a-t-elle vraiment existé et harcelé des féministes sur les réseaux sociaux ?, Cheknews.fr. Photomontage d’après liberation.fr 15 février 2019 ©CheckNews

While these mechanisms had no effect on the audiences most likely to embrace suspect information (Barrera Rodriguez, 2018), they constituted mutual monitoring among professionals. Thus the French media system has limited permeability, with the mainstream media collectively resisting the integration of questionable or fake information.

These conclusions remain partial for lack of better knowledge about another communication space that is more difficult to study – that of conversations on social networks or messaging. Many observations underscore that it is mainly within platforms that limit communication to a small circle (such as Facebook, Snapchat, WeChat, and WhatsApp) that strange, suspect, or manipulative information are most shared. This viral circulation, which under some circumstances can be significant, does not necessarily obey – this remains a question for research to explore – the same principle of organization of political values and of attention to the legitimacy of sources as higher levels of the pyramid. This is how the Yellow Vest movement might be interpreted. In the absence of a mainstream outlet, the public space does not polarize vertically, but rather horizontally, by opposing highly visible spaces (websites and Twitter) to the conversational space of Facebook. Unlike political polarization, which, in the American case, reflects an ideological differentiation between two Americas that increasingly oppose one another, the situation created in France by the Yellow Vest movement opposes mainstream media and the “Facebook population” according to a disconnection logic that the following figure represents.

In this context, what is important is not so much the boundary between truth and falsehood, as the opposition between the bottom and the top, the people and the media elites. This anger has been expressed through scattered acts of violence against journalists. The whole dynamic of the mobilization attests to a movement to make the periphery come to the center (from roundabouts to city centers, and then to Paris), from Facebook to the front page of leading mainstream newspapers. Seen from this perspective, the Yellow Vests movement appears to have successfully imposed its protest agenda onto a central public space that was ignoring it.

Bibliography

- Allcott Hunt, Gentzkow Matthew, 2017 – Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election, in Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 31, n°2

- Barrera Oscar, Guriev Sergei, Henry Émeric, Zhuravskaya Ekaterina, 2017 – Facts, alternative facts and fact checking in times of post-truth politics. Centre for Economic Policy Research

- Benkler Yochai, Faris Robert, Roberts Hal, 2018 – Network Propaganda. Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics, Oxford University Press

- Bronner Gérald – La démocratie des crédules, PUF, 2013.

- Gaumont Noé, Panahi Maziyar, Chavalarias David, 2018 – Reconstruction of the socio-semantic dynamics of political activist Twitter networks—Method and application to the 2017 French presidential election in PloS one

- Grinberg Nir, Joseph Kenneth, Friedland Lisa, Swire-Thompson Briony, Lazer David, 2019, Fake News on Twitter during the 2016 US Presidential Election in Science, n°363

- Guess Andrew, Nyhan Brendan, Reifler Jason, 2016 – Selective Exposure to Misinformation: Evidence from the consumption of fake news during the 2016 US Presidential campaign,

- Watts Duncan J. , Rothschild David M. , 2017 – Don’t blame the election on fake news. Blame it on the media in Columbia Journalism Review

![Fig. 1. The three layers of digital public space [authority; influence; conversation] © médialab](https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/3-couches-esp.-pub_EN-1024x285.jpg)

![Fig. 2. Polarization [alternative facts] © médialab](https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/polarisation-EN-1024x440.jpg)