When Constitutional Law Imagines Foreigners

16 November 2020

Migrant Labor: Policies Serving Production Systems

16 November 2020The Apparently Unstoppable Growth of Human Mobility in the Pre-Covid World

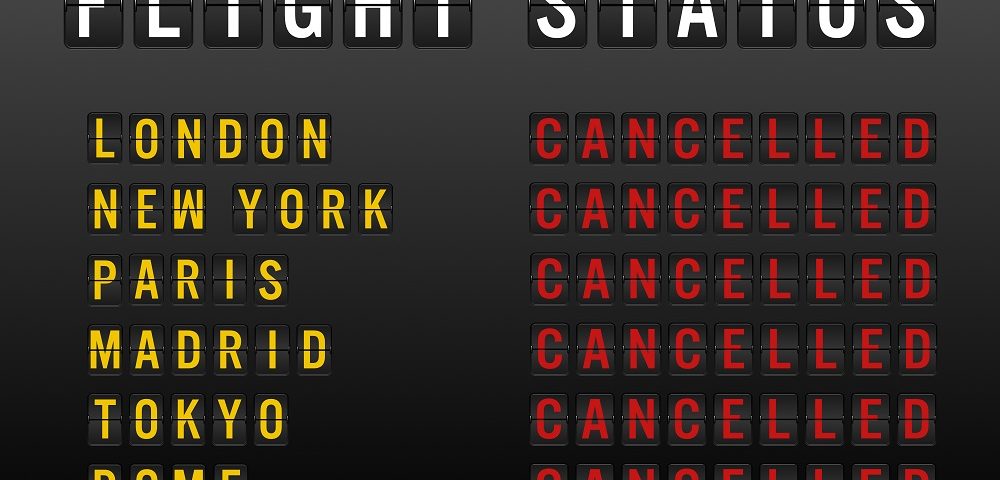

Fall in air traffic in Europe correlated with the spread of the coronavirus (in number of confirmed cases), March 2020. Source: Airports Council International Europe

Six months after the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared Covid-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the virus has taken the lives of almost one million human beings worldwide. Collateral damages in the socioeconomic realm have been huge as well. Among these, a precipitous drop in all forms of transnational movements. Due to the fear of contagion, travel was strongly discouraged if not forbidden in most places(1)Iacus, S. M., Natale, F., Santamaria, C., Spyratos, S., & Vespe, M. “Estimating and projecting air passenger traffic during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak and its socio-economic impact.” Safety Science, 2020.. While we still lack definitive figures, we know that major airlines cut between 50 and 95 % of their regular flights by late March only to recover timidly in the summer months. Insofar as it represents the demographic backbone and the ‘human face’ of globalisation(2)Smith, M. P. & Favell, A. (Eds.). 2006. The Human Face of Global Mobility: International Highly Skilled Migration In Europe, North America And The Asia-Pacific, 2006, Transaction Publishers., the almost total disappearance of cross-border movements of persons during the pandemic could be a precursor to a less integrated world.

This unexpected and traumatic event has interrupted an apparently unstoppable trend that had continued steadily for the preceding sixty years: the global rise of transnational travel(3)Deutschmann, E. “The Spatial Structure of Transnational Human Activity.” Social Science Research, 2016..In this short article, I document the size and shape of worldwide mobility before the Covid-19 pandemic, relying on systematic data that I have contributed to gather and analyse as director of a collective research project, and further discuss possible scenarios for the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis.

Global Mobility: A Steady Yet Unequal Expansion

Charles de Gaulle Airport, avril 2017, CC BY H. Naudet

For scholars of human mobilities, there are two sources providing regular and reliable information on the global volume and directions of cross-country flows: data on tourism, i.e., cross-border visits that include an overnight stay, collected by the World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO); and data on air passenger traffic provided by private companies (particularly, Sabre). Each of these sources under-reports the actual scale of movements. UNWTO data is incomplete in that it does not include people moving between countries for motives other than tourism (like returning residents).

It is also distorted because visitors from countries with few departures are not counted. International air passenger data, in turn, fails to count people who use other transportation means. By combining these two data sources, however, reliable estimates of global cross-country human mobility can be drawn. Through the careful integration of these statistics, a Global Transnational Mobility Dataset(4)Recchi, E., Deutschmann, E. & Vespe, M. “Estimating Transnational Human Mobility on a Global Scale”, Migration Policy Centre European University Institute, 2019 ; Gabrielli, L., E. Deutschmann, F. Natale, E. Recchi & M. Vespe. “Dissecting Global Air Traffic Data to Discern Different Types and Trends of Transnational Human Mobility” EPJ Data Science, 2019. was created. This dataset covers 196 sender and receiver countries in the form of a symmetric matrix of 38,220 cases (i.e., country pairs) per year. Spanning over the 2011-2016 period, the dataset reports 15.5 billion trips.

Overall, the Global Transnational Mobility Dataset estimates that there were 2.95 billion cross-border trips in 2016. Between 2011 and 2016, global mobility soared dramatically. In absolute terms, the number of travels grew by about 0.6 billion episodes per year. This growth (about 5% per year) is larger than the growth in world population (about 1% per year) over the same period. In this regard, transnational mobility is expanding much more than migration, which itself has not risen faster than the world population(5)Czaika, M., & De Haas, H. “The globalization of migration: Has the world become more migratory?” International Migration Review, 2014..

The largest mobility flows (‘trips’) on the planet occurred between China and Hong Kong and between China and Macao in Asia, between Germany and Poland and the UK and Spain in Europe, and at the USA-Mexico border in America. Conservatively, the mobility flows between these countries exceeded 30 million trips per year. In sharp contrast, among the entire collection of 229,320 combinations of country of origin and country of destination over six years, more than half amounted to less than one hundred country-to-country journeys per year. The overall structure of global mobility was thus extremely skewed.

Intra-Regional Mobility is Predominant

Air traffic in Africa, 2020 © IATA

Such an unbalance is embedded in a clear regional structure. Inter-regional mobility is far less common than intra-regional mobility. The largest share of international mobility revolves around Europe, where 46.9 % of world travels originate, the bulk of which occurs between European countries. Europe is by far the region with the highest number of intra-regional trips, followed by Asia. The Americas are behind, and the smallest number of trips take place within Africa and Oceania. Moreover, intra-regional mobility grew strongly in Europe and Asia between 2011 and 2016, while the Americas witnessed a smaller increase and Africa and Oceania had stable figures. There is thus no catch-up effect across world regions. Rather, the divergence between regions in terms of intra-regional mobility seems to widen over time. To have a sense of the magnitude of the difference, consider that transnational mobility within Europe is about twenty times the amount of mobility within Africa, in spite of the much larger population of the latter continent. Transnationalism—mostly but not exclusively through human mobility—is a hallmark of contemporary Europe(6)Recchi, E., A. Favell, F. Apaydin, R. Barbulescu, M. Braun, I. Ciornei, N. Cunningham, J. Diez Medrano, D. N. Duru, L. Hanquinet, S. Pötzschke, D. Reimer, J. Salamonska, M. Savage, J. Solgaard Jensen, A. Varela. Everyday Europe: Social Transnationalism in an Unsettled Continent. Bristol: Policy Press, 2019..

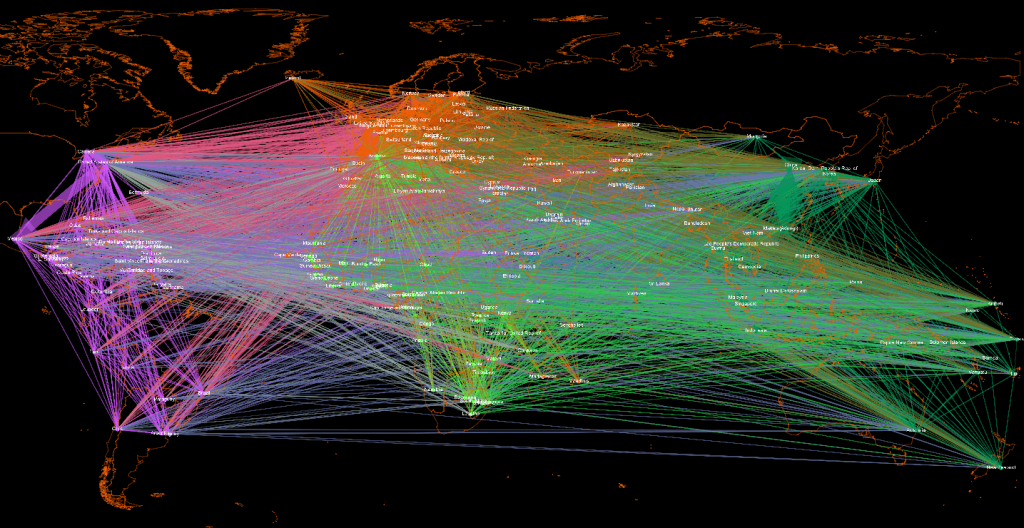

Another way of assessing the overall structure of population mobility flows is by applying a community detection algorithm that identifies the densest clusters in the network structure of worldwide travels. This technique has the advantage of yielding an informative visual outcome (figure). In this case, the travel network data includes the entire set of transnational mobility in 2016, provided each country pair is connected by at least 5,000 trips. For visual representation, the flows are centered in the country capitals.

Figure: The global network of transnational human mobility in 2016

Source: Deutschmann, E. & Recchi, E. “ Rapidly Increasing, New Open-Access Dataset Shows” MPC/EUI Blog, 2019.

Source: Deutschmann, E. & Recchi, E. “ Rapidly Increasing, New Open-Access Dataset Shows” MPC/EUI Blog, 2019.

The different clusters are highlighted with distinct colors. The automatic community detection confirms that human mobility is concentrated by world regions, rather than being truly global. Clusters overwhelmingly align with continents on the world map. The orange area emphasizes the tight connections within Europe, with some ‘extensions’ in Central Asia (including Russia) and a few former colonies in Africa. The violet lines reflect the American cluster, which spans across the Northern and Southern part of the continent. The blue lines signal the relatively stronger-than-average links between the Americas and East Asian countries. Lastly, the grey lines reveal the proximity through travels of Africa (especially South Africa, the most important mobility hub of the continent) with Oceania and Asia. The latter connection has become slightly but consistently more robust over the years.

An Uncertain Future for Global Mobility and International Relations

Yearly border-crossings reached 3 billion globally in the late 2010s. Transnational mobility was denser and grew at a faster pace in the richest regions of the world . Did the Covid-19 pandemic interrupt this trend for good? Is the peak of the age of mobility (and globalisation) behind us? Or will the trend resume as if nothing had happened?

© Shutterstock

The rise of transnational mobility in the post Second World War era responded to at least five strong underlying drivers: the technology-based reduction of travel costs, the capitalist interest in fostering the travel and tourism market, the growing affluence of the world population, the human cultural orientation to novel experiences, and the increasing political integration of some world areas (notably, the EU). In the face of the Covid-19 crisis, transportation technology has not waned and capitalism has not been subverted by the pandemic; however, the world has grown poorer, people have become more wary of the environmental costs and health risks associated with travels, and international relations have somewhat deteriorated. What’s next? Economies may recover. The demand for travel can pick up again, should the health conditions improve substantially. The supply of transportation and tourism facilities could follow suit, as infrastructures have not been disrupted. The bigger question is whether sovereign states will be favorable to re-opening to international mobility, or rather fall back on a nationalist default positioning: the world is made of insiders and outsiders who must be pigeon-holed territorially through borders and border controls. As they affect the scope of individuals’ life chances and horizons, political choices about mobility will ultimately shape the world to come.

Ettore Recchi is Full Professor of Sociology and membre of the Observatoire sociologique du changement. His research focuses on mobility (in its different forms), social stratification, elites, and European integration. He is also part-time professor in the Migration Policy Centre, European University Institute, Firenze. See his publications.

Notes

| ↑1 | Iacus, S. M., Natale, F., Santamaria, C., Spyratos, S., & Vespe, M. “Estimating and projecting air passenger traffic during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak and its socio-economic impact.” Safety Science, 2020. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Smith, M. P. & Favell, A. (Eds.). 2006. The Human Face of Global Mobility: International Highly Skilled Migration In Europe, North America And The Asia-Pacific, 2006, Transaction Publishers. |

| ↑3 | Deutschmann, E. “The Spatial Structure of Transnational Human Activity.” Social Science Research, 2016. |

| ↑4 | Recchi, E., Deutschmann, E. & Vespe, M. “Estimating Transnational Human Mobility on a Global Scale”, Migration Policy Centre European University Institute, 2019 ; Gabrielli, L., E. Deutschmann, F. Natale, E. Recchi & M. Vespe. “Dissecting Global Air Traffic Data to Discern Different Types and Trends of Transnational Human Mobility” EPJ Data Science, 2019. |

| ↑5 | Czaika, M., & De Haas, H. “The globalization of migration: Has the world become more migratory?” International Migration Review, 2014. |

| ↑6 | Recchi, E., A. Favell, F. Apaydin, R. Barbulescu, M. Braun, I. Ciornei, N. Cunningham, J. Diez Medrano, D. N. Duru, L. Hanquinet, S. Pötzschke, D. Reimer, J. Salamonska, M. Savage, J. Solgaard Jensen, A. Varela. Everyday Europe: Social Transnationalism in an Unsettled Continent. Bristol: Policy Press, 2019. |