‘Too many civil servants’: History of a Mantra

12 February 2022

Order and Disorder in French Public Media

12 February 2022 In his recently published Comparative constitutional litigation. A critical introduction to constitutional procedural law (LJDG, June 2021), law professor Guillaume Tusseau advances the undertaking he started in a previous book, where he questioned the current methodology for studying the action of constitutional courts (Models of constitutional justice. A methodological critique, in French and in Italian). At the same time, he delivers an unparalleled study on the implementation of constitutions.

In his recently published Comparative constitutional litigation. A critical introduction to constitutional procedural law (LJDG, June 2021), law professor Guillaume Tusseau advances the undertaking he started in a previous book, where he questioned the current methodology for studying the action of constitutional courts (Models of constitutional justice. A methodological critique, in French and in Italian). At the same time, he delivers an unparalleled study on the implementation of constitutions.

The comparative study of constitutions has always been at the heart of your work. In this book, you examine them from a litigation perspective. What is the origin of this undertaking?

Guillaume Tusseau: From my research based on dozens of constitutions around the world, I found that constitutionalism has been the dominant mode of organising political power in almost all states for over two centuries. More notably, the enforcement of constitutions is increasingly performed uniformly. It consists of entrusting specific legal bodies, namely courts, with the task of ensuring that other institutions respect the separation of powers, and that the fundamental rights of citizens are protected. This jurisdictionalisation of constitutionalism, which is apparent across all five continents, has been studied using interpretive frameworks that I believe have become obsolete, and even caricatural. My book attempts to address this dissatisfaction.

While everyone knows what a constitution is, the notion of constitutionalism is less familiar…

G.T: In a nutshell, it is the practice of using a constitution – understood since the 18th century as a supreme law expressing the will of the sovereign people – to structure political power. Jurisdictionalised constitutionalism emphasises constitutional litigation, i.e. the resolution by judges of difficulties implementing the constitution.

What types of conflicts can be handled at this level?

G.T: It can be a dispute between individuals, for example a neighbourhood disagreement wherein one party uses the constitution to block the other party’s claims. But there can also be conflicts between political bodies around constitutional violations and authority oversteps. Other cases involve antagonism from individuals unhappy to see their fundamental rights ignored by public authorities.

You speak of caricatured approaches. What are they?

Prefecture of Sucre and seat of the Constitutional Court of Bolivia CC-BY-2.0 Valdiney Pimenta

G.T: A widespread belief is that there are only two models of constitutional justice: the American model and the European model. According to this view, all U.S. courts are empowered to implement the constitution and thus to give it precedence over any other legal norm at the request of any litigant. By contrast, in the European model only specialised courts that differ from ‘ordinary’ courts – the constitutional courts – can adjudicate issues relating to the application of the constitution. While the dichotomy between these two models remains analytically dominant, many other configurations exist. Especially in recent years, constitutional justice has developed in almost all states. In order to accurately account for this variety, I saw the need to create new interpretative frameworks. To this end, it is essential to provide our students access to a global landscape of constitutional justice that goes beyond the usual suspects (the United States, Germany, Italy, France, etc.). The book therefore covers every region of the world..

How do you explain the development of constitutional justice on all continents?

In the direction of the Tunisian Constitutional Council. CC-BY-SA-4.0, Sami Mlouhi.

G.T: In Europe, this phenomenon became widespread after World War II. The argument often put forth was that a political majority did not suffice to ensure the legitimacy of a decision. A redefinition of democracy to encompass both majority rule and the protection of fundamental rights occurred. To achieve this, it seemed natural to rely on the establishment of an independent and impartial figure such as a judge. Today, it is inconceivable that a state would adopt a constitution without jurisdictional mechanisms to ensure its proper application. This is what I propose to analyse as a real cultural transformation..

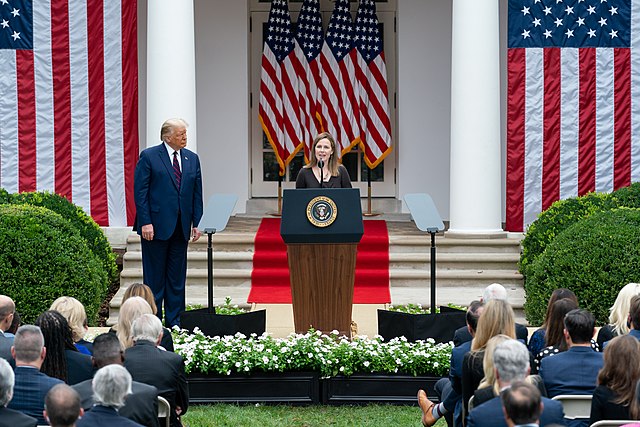

But there are cases where political authorities manipulate these bodies. A blatant example was Donald Trump’s appointment of a member of the Supreme Court who shares his political views…

Amy Coney Barrett alongside President Donald Trump at the White House, during his nomination as a Supreme Court nominee. Copyrights: Public domain

G.T: Yes, this is an interesting case. But it is not so unusual, to the point that ‘manipulation’ may not be the appropriate term. All U.S. presidents, with the Senate’s blessing, have appointed federal judges from their political parties. This generally tends to be seen as a practice of authoritarian or illiberal regimes, such as the one in Poland, where a major crisis in the appointment of members of the Constitutional Court emerged in late 2015, or in El Salvador, where the entire Supreme Court was disbanded in May 2021. But the link between the political sphere and constitutional courts is empirically apparent in all states, including the most respected constitutional democracies. In Germany, for example, appointments to the Federal Constitutional Court are based on both technical competence and political considerations that are well known and accepted. Some authors even see this, within certain limits, as a condition for the democratic legitimacy of constitutional courts.

With regard to illiberal regimes, it is important to eschew thinking that constitutional justice is merely a victim of the autocratic impulses of political authorities. My most recent research shows that it is not exceptional for constitutional courts to be active accomplices to authoritarian governance. They can validate coups d’état, allow an autocrat to stand for election indefinitely despite constitutional term limits, facilitate the undermining of pre-existing liberal legislation, justify resistance to supranational law, etc.

What elements of constitutional justice did you comparatively study?

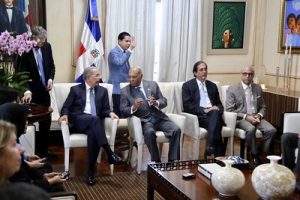

President Danilo Medina (Dominican Republic) receives the Governing Board of the World Conference on Constitutional Justice. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Romelio Montero/Presidencia República Dominicana

G.T: I am convinced that the only way to understand our jurisdictionalised political societies is to combine two perspectives that are most often oblivious to one another. The first is a political science perspective, which highlights the power of constitutional judges, and the second is a procedural law perspective, which focuses on the technique judges use, and how they examine requests and make decisions. I have tried to embrace all of these elements in my book. The first part provides an intellectual history of constitutional justice. The second part sheds light on the methodology that enables comparison of constitutional justice systems. The third part studies the judicial branch, i.e. the individuals who adjudicate constitutional justice, and the fourth part focuses on the institution itself. The next part describes the competences of the constitutional courts (norm validation, electoral disputes, protection of fundamental rights, etc.). The sixth part captures various phases of the constitutional process, while the last part examines the decisions of constitutional judges and the way in which the decisions are imposed, with varying levels of success, on other legal actors.

So you can measure the health of a democracy by its constitutional justice?

G.T: Actually, no. Authoritarian regimes have deployed constitutional mechanisms that are no less developed than those used in so-called “advanced” democracies. One of the goals of the book is precisely to decipher the grammar of current constitutionalism, in order to demonstrate that tools forged in the crucible of a liberal and democratic doctrine that emerged in the 18th century have paradoxically come to serve other types of political projects. As the subtitle I have chosen indicates, it is therefore important to avoid any glamorization of the subject, and to keep a critical perspective on the technical refinements of contemporary rule of law.

Interview by Hélène Naudet, communication, Vice Presidency for Research

Guillaume Tusseau is a professor of public law at Sciences Po. He is both a constitutionalist and a legal theorist and focuses on the analytical theory of law and the thinking of Jeremy Bentham.