“American things: true, metaphorical and anachronistic stories of trauma, colonialism, slavery, racism and social terror, through the ages and the worlds of the hemisphere”: this lengthy title given by Edward Sullivan to his paper relocates our research subject in the current historical context. The author outlines here what he calls his “imaginary exhibition” by showing that objects have both meaning beyond their simple appearance and that they also, as wrote Walter Benjamin, “become stranger as centuries go by”.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Les choses américaines

Real, Metaphoric and Anachronic Stories of Trauma, Colonialism, Slavery, Racism and Social Terror Throughout Time and Geographies Within the Hemisphere

Edward J. Sullivan

The following text consists of several interdependent modules: an introduction, a “manifesto” of sorts, that presents those general concepts constituting the basis of a selection of objects for an “imaginary exhibition,” as well as reflections about the concept of the “gift” as expressed by the philosopher Marcel Mauss.

The Imaginary Exhibition: General concepts and Images

All things have meanings beyond their appearances. When viewing an object, it first appears as something that occupies space, whether the real or the psychic realm. When contemplated as having lives of their own, objects – palpable things that are present in our physical domain, or images of objects or accumulations of things (as in a painted or photographed still life, or as in a sculpture depicting inert entities) – lead us to question their appearance. Are we really seeing what they are? Do we know what they are used for or how they were employed in the past? Where do they come from and what does their provenance mater? What is their materiality? A trompe-l’oeil still life is not a “thing.” It is a simulacrum of thingness, a sign that points us in multiple directions of interrogation.

Within the context of this discussion, which takes the form of a conversation or a series of proposals, I wish to problematize a variety of observations on objects. Specifically, the objects which I shall use as anchors for each section of what I could call the “musée imaginaire” to borrow a term from André Malraux, or, more precisely, an “éxposition imaginaire” are all representative of the Americas.1André Malraux, Le Musée Imaginaire (Paris: Gallimard, 1965) I use this term “the Americas” in its broadest possible description, examining visual phenomena from a broad swath of chronology and a multiplicity of geographical locations from North, to Central and South America and the Caribbean. I do not wish to “flatten” or minimize the vast cultural or sociological differences between the many locales that constitute “the Americas” but as all of my work has been about border crossings and comparative examination of visual and material cultures, I am interested in investigating the multiple manifestations of material phenomena which may play a role in establishing certain norms or patterns of cultural production in the post-colonial western hemisphere.

I present herein a series of objects, organized according to modules, as they might be exhibited within a series of galleries. The different groupings should work together to shed light on cultural themes as well as problematic anthropologies. Within this ensemble, the various components of this “imaginary exhibition of objects from the Americas” should combine to create coherent commentaries relevant to trans-historic and trans-geographic subjects common to the history of the Western Hemisphere. I refer as well to what the Spanish linguist, novelist and philosopher Miguel de Unamuno would describe as the “inner history” (intra historia) of the lives of objects.2Miguel de Unamuno, En torno al casticismo (Madrid: Cátedra, 2005) For Unamuno, the concept of ‘inner history” concentrates on the small and seemingly innocuous or even unimportant elements of memory and “reality” to elucidate the larger picture of the circumstances of a given time or place.

In 2007 I published a book entitled The Language of Objects in the Art of the Americas.3Edward J. Sullivan, The Language of Objects in the Art of the Americas (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007) It dealt with similar problems as I discuss in this series of proposals. In the introduction of that volume I wrote the following: “This book consists of a series of individual yet inter-related studies about the development of art and visual culture in the Americas. The prism through which the phenomena dealt with here are observed is the “object” broadly described. I view the object across the intersecting dimensions of time, space, materiality and artistic practice in the Americas as it intersects with that in other parts of the world.”

Before continuing with my initial propositions regarding a series of “things” that I have chosen as a sort of “aide mémoire” that would point to a virtually infinite number of historical, psychic or aesthetic (etc.) significations, I think it appropriate to cite the words of Jean Baudrillard, who declared that all objects have two functions: they may be used or they may be possessed.

Fig. 1 : Cihuateotl . 15-16 siècles. Mexique. Stone. 66 x 43.8 x 43.2 cm.

New York. Metropolitan Museum of Art (00.5.30). Photograph courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, public domain.

Figure 1: Cihuateotl

In the Metropolitan Museum, there is this strange, enigmatic and certainly frightening object. It represents “Cihuateotl” – a monstrous phantom – a demon- a simulacrum of terror from the Pre-Hispanic Valley of Mexico. It is a representation (half human, half animal) of a woman who died in childbirth. She then became a devil-like creature who haunts the underworld and the earth. The real meanings of Cihuateotl are as obscure as its origin. Its earliest use is unknown but it was certainly meant to strike fear into the heart of the beholder. This obscure “thing” that serves as a testimony to what was thought to be “barbarous Mexico” was in the Museum by the 1900; it came from the Louis Petich collection in New York, but nothing else is known about its provenance.

Fig. 2 : Noble lady with her slave wife. Vicente Albán (Equateur. 18e siècle). c.1783. huile sur toile. 81.3 x 106 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photograph courtesy Los Angeles Museum of Art, public domain.

Figure 2: Vicente Albán: Noble Woman with Her Female Slave

In many parts of the colonial Americas, a caste system was firmly in place until the era of independence from Spain in the early nineteenth century. A genre of painting called “pinturas de castas” emerged, mainly in Mexico but also in Peru and Ecuador. These images served as still lifes of the human body: taxonomies based on racial background, skin color and supposed “inherent” personality characteristics. Such paintings as this (sometimes done in grouping of the traditional 16 castas in one images, sometimes in individual scenes) inevitably contained additional information about the flora and fauna of their place of their origin. Created for Enlightenment-era European audiences interested in the new taxonomies from across the Atlantic Ocean, these scenes represented codifications of racial and social attitudes. Here, a creole women (European, but born in Latin America) shares the space with her Afro-descendant servant. But it is equally evident that they form only the human element within a larger “scenography of exotic things” along with the landscape and the “fruits of the earth” (all numbered and identified at the lower left).

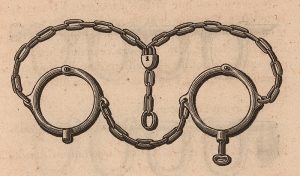

Fig. 3 : collar and slavery chains, published in Faits relatifs à la traite des noirs (Paris: Société de la morale Chrétienne. Comité pour abolition de la trait des noirs, Paris, 1826), p. 15 John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.Photo graph courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, public domain.

Figure 3: Slave chains

These objects testify to the visual iconography of the horrors of slavery that may be best understood not through grandiose paintings of scenes of colonial history, but by observing and internalizing the reality of these objects – or, rather, of these things – signs of trauma and terror.

Fig. 4 :Butaca (Domestic or ecclesiastical armchair).

Venezuela, c. 1750. Mahogany and pardillo 102.11 x 64.0l x 67.95 cm.

Los Angeles county Museum of Art, Gift of Adriana Cisneros in honor of Gustavo Dudamel.

Photograph courtesy Los Angeles County Museum of Art, public domain.

Figure 4: Domestic or Ecclesiastical Chair

Created in the 18th century for an aristocratic domicile in Caracas, Venezuela, this elaborate “butaca” is now in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Is it a simple object, a chair? Upon it sat the colonial or the ecclesiastical authority of the Spanish territory. It is representative of the might, power and economic strength of Spain and the Catholic Church in colonial times. The Chair speaks eloquently of the authority of government and the abuses, the enslavement of indigenous peoples throughout the American colonies.

Fig. 5: Raphaëlle Peale, “Still life with sweet cakes”.1818. Oil on canvas, 27.3 x 38.7cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Maria DeWitt Jessup fund, 1959). Photograph courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, public domain.

Figure 5: American artist Raphaelle Peale “Still Life with Cake”

19th century artist Raphaelle Peale (member of an important dynasty of “quasi-official” painters of the first half of the century) continues a tradition of European still life painting. It is manifestly related to northern European still life pictures with sweets. Here the artist creates a scene of a tempting desert with a cake cut into four pieces, grapes and a glass of wine. What makes this image American and what does it recall? The answer to this is one key word: Sugar. The economies of the Caribbean, the southern United States and elsewhere were made from the industry of sugar which was processed in the “ingenios azucareros” of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Jamaica and so many other places, then sent for refinement to the factories in the north, such as those in Brooklyn.

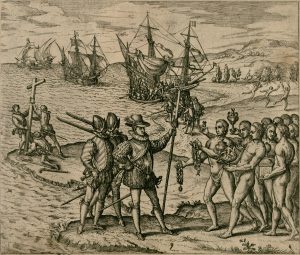

Fig. 6: Christopher Columbus on his first trip to the Americas, welcomed by the inhabitants carrying many gifts, in Theodore de Bry’s Americas: 1594. University of Houston Library. Photograph courtesy University of Houston Digital Library, public domain.

The Gift

Figure 6: “The Discovery of America” by Théodore de Bry

It is important to cite here a fundamental theory within the framework of the “inner life” of objects; that of the concept of “the gift” as articulated and elaborated by the French philosopher Marcel Mauss in his “Essai sur le don: forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques” published in 1923-24.4Marcel Mauss, “Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétiés archaïques,” Année sociologique, 1923-24 seconde série, tome 1 This text, so influential for writers and anthropologists such as Jean Beaudrillard, Jacques Derrida, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Georges Bataille and others, deals with the case of indigenous peoples of the Northwest Pacific coast of the U.S. and Southwest Pacific coast of Canada, and the phenomenon of the “potlach” (a ceremony of exchange within the “economies of the gift” during the first era of globalism). We may follow the spirit of Mauss’s theories about those mutual obligations implied by the exchange of gifts (which he defines as reciprocity), a key component of Mauss’s explanation of the gift, in our analysis of this image, one of many prints by the writer and artist Théodore de Bry, published in his late 16th century compendium entitled America (published originally in a Latin edition in Frankfurt in 1596).

This collection of vignettes illustrates scenes and stories fancifully recreating the important moments in the first encounters of indigenous peoples with their European colonizers. This book had great commercial success in 17th century Europe. The scene shown here describes the beginnings of colonialism in the Caribbean and the arrival of Christopher Columbus on the island of Guanahani (as it was called in the Taíno language), located in the Bahamas chain – a place the “conquistador” renamed San Salvador. Columbus and his soldiers stand before a group of Amerindians who bring them gifts, probably objects made of gold. At first sight, the Europeans offer nothing similar. However, this is not exactly true. The cross, planted in the ground behind the Spaniards, constitutes the gift that they bestow on the Taíno people: the rule and the domination of the cross and the autocracy of Spanish power form the objects of exchange in this poignant and symbolic illustration – an exchange marked by deception, cupidity and the start of a long history of destruction and colonial chaos.

[1] André Malraux, Le Musée Imaginaire (Paris: Gallimard, 1965) [2] Miguel de Unamuno, En torno al casticismo (Madrid: Cátedra, 2005) [3] Edward J. Sullivan, The Language of Objects in the Art of the Americas (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007) [4] Marcel Mauss, “Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétiés archaïques,” Année sociologique, 1923-24 seconde série, tome 1

Bibliography

Andre Malraux, Le Musée Imaginaire, Paris: Gallimard, 1965.

Marcel Mauss, “Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques,” in Année sociologique, second série, tome 1.

Marcel Mauss, Essai sur le don, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2012.

Edward J. Sullivan, The Language of Objects in the Art of the Americas, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

Miguel de Unamuno, En torno al casticismo, Madrid: Cátedra, 2005.

Edward J. Sullivan is Professor of Modern Art History and Deputy Director at the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University. Author of many books on the visual cultures of the Americas, he has also curated numerous exhibitions in museums in the United States, Europe and Latin America. His most recent exhibition, in 2019, was entitled Brazilian Modern: The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx for the New York Botanical Garden. His book Making the Americas Modern (London, 2018) is being translated into French for publication by the presses du réel.