This is how Elvan Zabunyan summarizes the status of this precious and coveted metal, intrinsically linked with the history of slavery. The author unveils a significant reversal in this status : the men and women of soul and hip hop using gold, in the shape of heavy chains, most notably, in order to re-capture its power. She studies this new, contemporary, symbolism, while also looking into older objets bearing the marks of colonial power, some of which were recently shown at an exhibition dedicated to slavery at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Elvan ZabunyanThe body gold

This text is made of fragments of a manuscript to be published in 2023 by B42, in their series “Culture”, edited by Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc. It will focus on the history and memory of slavery as a political tool, as well as its use for thinking through contemporary art.

Gold is a contrast. A precious, coveted, metal, it is inseparable from the economic exploitation of the bodies involved in its mining. People enslaved in gold mines from the 15th century onwards, first on the western coasts of Africa, and then in the Americas (notably in Brazil, Panama, Colombia and the United States), were referred to as “black gold”. In her 2007 book, Lose your mother, A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, Saidiya Hartman, a professor at Columbia University, recounts her journey to Ghana in search of the sources and vestiges of African slavery. Her book intertwines personal (some of her ancestors were slaves from Suriname deported there by the Dutch) and collective memory. In the first chapter, entitled ‘Afrotopia’, she refers to Thomas More’s Utopia, published in 1516, contrasting the term ‘utopia’ with ‘afrotopia’. She underlines the contradiction of a utopian society replicating the subjugations of slavery and quotes an extract from the “Second Book” of Utopia 1S. Hartman, Loose Your Mother, A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007, p. 47.. Not mentioned by Hartman, the beginning of More’s sentence is important to understand the larger context of this quote:

« [They eat and drink from earthen ware or glass, which make an agreeable appearance though they be of little value], from gold and silver they make chamber pots and all the humblest vessels for use everywhere, not only in the common halls but in private homes also. Moreover they employ the same metals to make the chain and solid fetters which they put on their slaves »2T. More, Utopia, Book 2, p. 79..

In More’s story, the island of Utopia is a place where people live without money and the values of contemporary society are overturned: gold follows this narrative. Devalued and degraded, gold is given the same status as slaves. Hartman continues: “What better illustration of the degradation of gold than its capacity to transform persons into things, what better example of its offensive character than the excremental conditions of the barracoon; what better sign of its mutability than the “black gold” of the slave trade.”3Saidiya Hartman, op. cit. p. 47.

Between the gold chains, bracelets, and necklaces, signs of a lowered social status for More, and gold as a source of “degradation” for Hartman, another, complementary, hypothesis, can be put forward, one that treads a parallel yet different path. Let us consider a reversal: that of the reappropriation of their objectified bodies by women and men, releasing themselves from this devaluation by wearing gold jewelry. Their agency acts as a source of social critique and political emancipation from racial discrimination. In the contemporary period, the study of certain artistic practices stemming from performance and popular culture such as soul or hip-hop music confirms that gold worn to excess is an expression of power.

Fig. 1. Box of the Dutch West India Company, 1749, Gold and tortoise shell, 5,8 x 18, 11, 9 cm

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (NG-NM-824).

Gold Coast

The long history of gold and slavery runs parallel to a chronology punctuated by European geopolitical domination. For example, the coasts of present-day Ghana underwent colonial occupation, first by the Portuguese, then by the Dutch and finally by the English. In 1482, barely ten years after their arrival, the Portuguese built a fort – São Jorge da Mina – to protect their trade. 130 years after the fort was built, the Dutch settled on the shores of the Gold Coast. Between 1599 and 1608, two hundred Dutch vessels were recorded as having made merchant voyages to the Gold Coast and the adjacent African coasts. In addition to gold and ivory, it was the enslavement of African men and women, and their deportation to the Americas, that greatly enriched the beneficiaries. Around 1611 the Dutch built their first fort, which they later named Nassau after a medal-winning soldier.

Fig. 2. Lid for Box of the Dutch West India Company, 1749. Gold and tortoise shell, 5,8 x 18, 11, 9 cm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (NG-NM-824).

The gold box

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam holds a small box (5.8 x 18.11.9 cm) made entirely of gold and tortoiseshell, dated from 1749, and commissioned by the Dutch West India Company as a gift for Governor William IV, Prince of Orange. The aforementioned forts are represented on some of the sides of the box. On its underside, letters forming ‘AFRICA’ are written in gold following the outline of the West African coastline. The object embodies Dutch colonial power. The box was shown in 2021 in the exhibition “Slavery”, held at the Rijksmuseum, which put forward a critical re-reading of the pieces in its collection, placing them within a global history and underlining both the economic reasons for the violence of slavery as well as the role of the Netherlands in the trade.

On the lid of the box, two African figures, one male and one female, are dressed in a simple loincloth. The woman is daydreaming and leaning, in an elegant gesture, against the gold nugget placed, in relief, at the heart of the composition; the man, whose protruding muscles attest to his strength, carries an elephant’s tusk on his shoulder. The contrast between the luxuriously elegant metal in the rococo style and the raw mineral material is noticeable. In the background, a scene in miniature confirms the trade of the Africans: a man dressed like a European appears to be negotiating with a group of undressed people. According to the museum’s curators, this scene is one of the earliest visual proofs of the trade known, an image that none of them had considered until this exhibition. Sat, thronelike, on the gold nugget, is a figure of Hermes/Mercury: in one hand he holds the initials of the West India Company as a shield, and, in the other, his caduceus. In ancient Greek and Roman mythology he was the god of travelers, merchants, and thieves. If you look closely at the gold nugget, you can see small white pebbles. Gold has a cosmic origin. Five billion years ago, the precious metal was born from the collision of two neutron stars, and the debris expelled at the time of the explosion was scattered in different parts of the earth. The development of mining techniques that relied on the work of workers was born from those who coveted this rare wealth.

Fig. 3. “Unidentified man with gold mining equipment and wearing a U.S. beltplate”, daguerréotype, non daté, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.]

Gold rush

The famous California gold rush coincided with the birth of the daguerreotype. Daguerre invented this photographic process in 1839, barely ten years before the discovery of gold in California. The almost simultaneous development of the techniques for, on the one hand extracting gold, and, on the other, the medium allowing the record this process in images, is worth underlining. As the use of the daguerreotype increased quickly in the United States, pre-industrial working conditions in the mines were memorialized, forging unprecedented images of the geological landscape. Some rare daguerreotypes show African-American workers 4See J. L. Aspinwall, Golden Prospects, Daguerreotypes of the California Gold Rush, Kansas Ciy, Missouri, The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Hall Family Foundation, 2019.. As curator Jane L. Aspinwall reminds us:

“Additionally, large groups of non-white workers were perceived as threatening to the individual white miner; American Indians working on ranchos, the Chinese allegedly laboring for slave masters in China, Mexican bonded under peonage systems, and black slave gang labor from the Southern United States were all unwelcome” 5J. L. Aspinwall, « Diversity in the gold fields », op.cit., p. 131

Working conditions in the California gold mines were terrible, leading to disease and death. An article published on 30 November 1849 in The North Star, founded in 1847 by Frederick Douglass, a former fugitive slave who became one of the greatest abolitionist leaders in the United States, compared these conditions to those of “any Negro on a sugar or cotton plantation”6The North Star, 30 November 1849, [https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84026365/1849-11-30/ed-1].

Fig. 4. Thierry Lefébure, Torse, 1998

Polaroid. Image courtesy of the artist.

The body decked in gold chains

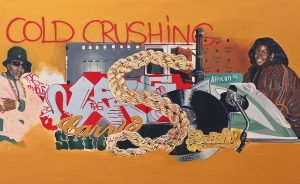

In August 1972, singer-songwriter Isaac Hayes (1942-2008) performed his iconic song “Shaft” at the Wattstax festival, organized to commemorate the Watts riots in Los Angeles, which had broken out seven years earlier. In a Cadillac escorted by motorbikes, the star was driven unto the stage to the cheers of the audience. The singer, wearing dark glasses, a colorful cape and a wide-brimmed hat, took to the stage, the music began, everyone waiting with bated breath. Hayes removed his cape, revealing a powerful body strapped with gold chains7The Wattstax festival was held on the 20th of August 1972 at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, in front of 112 000 spectators. Isaac Hayes’ performance can be viewed here: [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OctVizcgBcY].. This image of an African-American Spartacus, a symbol of soul music, chained but free, is one of the most representative of the aforementioned agency. It anticipates the appropriation by hip-hop artists of ostentatiously worn gold jewelry. The images of rappers wearing gold necklaces, bracelets, earrings and chains in the 1970s pay tribute to their enslaved ancestors. By using these, they repeat in a tautological and paradoxical way a liberating gesture, tracing at the same time an iconographical genealogy. Archetypes are reiterated by stigmatizing them to the point of caricature, until the stereotypes they embody become exhausted and crack.

Thomas More wrote in Utopia that golden chains were worn by the most penitent slaves. Black popular culture in the early 1970s was contemporaneous with a growing number of police brutality cases, African-Americans incarcerated in the United States under the pretext of drug and crime control, losing their lives in gang shootings or becoming victims of stray bullets.

Fig. 5. Jay Ramier, Cold Crushing, 2018

Acrylic paint on canvas, 180 x 290 cm,

Image curtesy of the artist.

Wearing gold became a way of asserting one’s dignity by freeing oneself from centuries of both exploitation and instrumentalization of the mind and body. Owning gold jewelry to the point of excess also became a means of taunting North American capitalism and the social and racial discrimination it induced. By confronting their history, wounded by forced labor, as well as the memory of their elders, artists created a unique and pioneering aesthetic; translating gilt bodies and their meanings.

[1] S. Hartman, Loose Your Mother, A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007, p. 47. [2] T. More, Utopia, Book 2, p. 79. [3] Saidiya Hartman, op. cit. p. 47 [4] See J. L. Aspinwall, Golden Prospects, Daguerreotypes of the California Gold Rush, Kansas Ciy, Missouri, The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Hall Family Foundation, 2019. [5] J. L. Aspinwall, « Diversity in the gold fields », op.cit., p. 131 [6] The North Star, 30 November 1849, [https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84026365/1849-11-30/ed-1]. [7] The Wattstax festival was held on the 20th of August 1972 at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, in front of 112 000 spectators. Isaac Hayes’ performance can be viewed here: [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OctVizcgBcY].

Bibliography,

Aspinwall, J. L., Golden Prospects, Daguerreotypes of the California Gold Rush, Kansas Ciy, Missouri, The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Hall Family Foundation, 2019

Bradley, R. N., ‘Re-Imagining Slavery in the Hip-Hop Imagination’, South: A Scholarly Journal, vol. 49, n° 1, Autumn 2016, pp. 3-24.

Forret, J., ‘Slave Labor in North Carolina’s Antebellum Gold Mines’, The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. 76, n° 2, April 1999, pp. 135-162.

Hartman, S., Loose Your Mother, A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

Jones, E. P., & Graham, M., “An Interview with Edward P. Jones”, African American Review, vol. 50, n° 4, Winter 2017, pp. 1081-1098.

Sint Nicolaas, E., & Smeulders, V., (ed.), Slavery, Amsterdam, RijksMuseum, Atlas Contact, 2021.

Smith, S. L., ‘Remaking Slavery in a Free State: Masters and Slaves in Gold Rush California’, Pacific Historical Review, vol. 80, n° 1, February 2011, pp. 28-63.

Van Der Ham, G., Tarnished Gold, Ghana and the Netherlands from 1593, Amsterdam, Rijks Museum, Vantilt, 2016.

Elvan Zabunyan is an art critic and professor of contemporary art at Rennes 2 University. Her forthcoming book will focus on the memory of slavery as a political tool in North American and Caribbean contemporary art. She has published extensively, both monographs and articles, the latter in edited volumes, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, both national and international. She recently co-edited Constellations subjectives, pour une histoire féministe de l’art (iXe, 2020) and Decolonizing Colonial Heritage, New Agendas, Actors, and Practices in and beyond Europe (Routledge, 2021). Her most recent publications include the essay “Revealing the past, illuminating the future: Kapwani Kiwanga’s flashbacks”, in Afterall, n°52, 2022, as well as a dialogue with Harmony Hammond in the spring issue of Les Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne, n°159.”