That the so-called “Spanish flu,” which claimed millions of lives worldwide between the spring of 1918 and the latter half of 1919, left almost no trace in art is surprising, to say the least. It is this mystery that has been plaguing art historian Thibault Boulvain, and which he has set out to unravel, using Egon Schiele’s final painting, The Family (1918), depicting a couple and their child on the brink of disappearance, as a starting point. This question prompts a broader one: what do we expect from an image of illness? And to what extent might a work of art resist interpretation—especially when we try to draw from it meanings it may not possess, or even be aware of?

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac and Thibault Boulvain

Thibault Boulvain Art in the time of influenza: some points for consideration

A Family

Between March 1918 and the summer of 1919, the Great Influenza – also known as the Spanish Flu – caused between 50 and 100 million deaths worldwide. “No other pandemic in the history of the world has killed so many”1Anne Rasmussen, in an interview with Florence Rosier, Le Temps, November 2018.. While there are photographs depicting masked individuals, nurses, bedridden patients, and sanitary measures, artistic testimonials appear to be much rarer.

The Family by Egon Schiele is often invoked to “illustrate” the devastation of the pandemic, which, at the end of 1918, had claimed the lives of all three figures represented: Schiele, Edith, his wife, and their unborn child. However, this painting predates their deaths by several months, and they were still healthy when they were depicted here. Just as Roland Barthes, when he looked at a childhood photograph of his mother, saw her dead and not as a child, the “Spanish” flu transforms The Family into a potent image, a symbol of the catastrophe independent of the artist’s intent. The artwork becomes a site of memory, anchoring individuals and giving tangible form to disaster. It renders us contemporaneous with the tragedy, placing us in the presence of its victims—themselves unaware of their status.

The post-mortem photographic portraits of Schiele by Martha Fein, where he “poses” even in death, certainly bear witness to these events more effectively. As for the artist himself, if he bears witness to the epidemic, it is primarily through the portraits of his ailing wife and, perhaps, in the post-mortem portraits of Gustav Klimt, created at the morgue on February 7th 1918, although we remain unsure whether Klimt actually died of influenza. Schiele held Klimt in high regard and his death would only later be evoked by a plain empty chair: the initial sketch of The Friends 2For the poster for the 49th Vienna Secession Exhibition in 1918., created before Klimt’s passing, still showed him seated at the table.

Old things

Fig. 1: Caricature in the newspaper Kikeriki, dated 27th of October 1918. Austrian National Library

When the cholera epidemic struck Paris in 1832, Chateaubriand lamented the lack of images of the disaster, as well as its “depoetization” 3A.-M. Mercier-Faivre & C. Thomas, éd. by, L’Invention de la catastrophe au XVIIIe siècle. Du châtiment divin au désastre naturel, Droz, 2008, p. 28.. Nothing, for him, lived up to the magnitude of the event, which was expected to align with the romantic imagination the writer had of it. In 1865, François Chifflart would meet this demand with Le choléra sur Paris, an “extraordinary image” that draws on the clichés of the “plague” genre 4A. Camus, La Peste, Gallimard, 2012, p. 48.. It demonstrates that one of art’s ways of life is to rely on leitmotifs—ancient elements rich in symbolic power, capable of conveying the gravity of an event. In this case, it serves to frighten the present with the specter of an ancient disaster.

During the influenza epidemic, Alfred Kubin evoked the traditional form for such an event: a reaper (The Spanish Disease or The Reaper, 1918–1920). This figure harks back to the “dance macabres” and the triumphs of death from the medieval and early modern periods, but, at the time, this type of old imagery of epidemic terror was quite rare, mostly confined to press illustrations.

Chateaubriand wanted cholera to look like the plague because he longed for the past, forgetting that if history is never the same, neither are its forms. The artistic representation of an event can be more complex than a simple, obvious reaction or an explicit “illustration.” Its manifestations and clues may disappoint by their scarcity or their “weakness” compared to our expectations. They can disorient us through their form as counter-rhythm, disruption, pause, silence, absence, a departure from usual artistic conventions, or as subtle details, among other expressions.

The shapes of history

Fig.2: Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway, 1925, London, Hogarth Press

Thus, in 1918, a slight alteration in composition, an empty chair, a discreet absence, might have transformed Egon Schiele’s poster for the 49th Secession exhibition into an image of the influenza.

Art invents events, gives shape to history, no matter how singular those forms may be. Millard Meiss observed this when he studied the impact of the plague in the art of Giotto and Masaccio: he was, during his research, faced with the “twined silence of art history and images”, encountering “a remarkable iconographic gap in the figurative representation of the plague itself” 5G. Didi-Huberman, L’humanisme altéré. La ressemblance inquiète, I, Gallimard, 2023, p. 95.. He was therefore compelled to seek the plague elsewhere than in its “expected” images, to take into account, through hypotheses and interpretation, other, unexpected, shapes for the event.

In the field of literary studies, Elizabeth Outka approached the influenza epidemic in a similar manner, interpreting works by William Butler Yeats, T. S. Eliot, and Virginia Woolf through the lens of the trauma caused by the pandemic, whose expression, she argues, is “coded” 6E. Outka, Viral Modernism. The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature, Columbia University Press, 2020.. The liveliness, the kind of joy that inhabits Clarissa Dalloway, whom Woolf reveals to have survived the “Spanish flu,” is thus interpreted in light of the event, as both its consequence and a testament to it.

From the point of view of visual studies, the field is certainly no less open, provided we are willing to reflect on the very nature of art, which is nothing other than “an expression of the world” 7J. Giono, « Arcadie ! Arcadie ! », January 1953, in Provence, Gallimard, 1993, p. 134., a representation of reality and of the truth. What it encompasses in terms of intuition, imagination, and the unconscious—elements that make it complex, unstable, and full of potential—places us partly on the side of the “unverifiable” 8See C. Einstein, « La discontinuité même », in La discontinuité même, l’écarquillé, 2021., just as the interpretative act inevitably invites multiplies meanings, by engaging with our knowledge, memory, imagination, and unconscious. The art historian walks a tightrope: they must find the balance between facts, the demand for objectivity, and the irresistible appeal of engaging with a story during the act of interpretation. It is that storytelling that allows for the “invention” of an event: by being open to the variety of its forms, by imagining it enough to recognize it where it does not even resemble itself.

The bad dead

In this respect, if we can see in an empty chair, painted by Schiele in 1918, an image of Klimt’s death, then Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair, B3 (1925), or Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Armchair No. 41 (1930–1931), among others, may be no less significant. They remind us that, as early as the 1920s, design had a social function: to support advances in hygiene and public health. The modernist project did not, either, overlook the fact that it was partly born in war hospitals and sanatoriums, where the impeccable forms of its rationalism were conceived. As such, in 1921, Arthur Conan Doyle described this new world as “hard, sharp, and bare, like a lunar landscape” 9Arthur Conan Doyle, in 1921, quoted by Laura Spinney in La Grande Tueuse. Comment la grippe espagnole a changé le monde, Albin Michel, 2018, p. 307., even as he engaged in table-turning séances following the death of his son from influenza in late October 1918.

Fig. 3: Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror [Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens], 1922, Prana Film Berlin GmbH (prod.), 94 m.

Conan Doyle is not the only one to commune with the dead: Abel Gance awakens them to denounce their oblivion and their hecatomb in 1922, just as Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau and Hanns Heinz Ewers, in their respective mediums (Nosferatu, Nachtmahr: Strange Tales), reawaken an old monster.

Since the “Spanish flu” fueled xenophobia, the resurgence of the vampire — a symbolic expression of a threat, a contamination coming from the “wild” East—deserves scrutiny, just as much as the plague epidemic spread like an evil by Count Orlok in Murnau’s Nosferatu.

Bringing together the undead of Gance and Murnau allows for a reenactment of the encounter between the war and influenza, as suggested at the time by press illustrations where the disasters conflate and merge—much like in Kubin’s work. This offers a partial answer to the absence and silence of images of the influenza: the war overshadowed everything, consumed everything, leaving little room for the pandemic to “exist,” particularly in terms of its representations and its memory. Moreover, the simultaneity of the two events blurs them: when Ernst Ludwig Kirchner depicts himself as ill, is he referring to his psychological distress caused by the war, or to the flu? If Clarissa Dalloway has such a drive for life, it is also because the war is over. And let us consider the works of John Singer Sargent, Interior of a Hospital Tent and Gassed (1918–1919): the narrative of combat prevails, as does the testimony of the disasters of chemical warfare. And yet, while working as a war artist, Sargent was hospitalized in a military hospital due to the flu, where he encountered both gas victims and other patients. In The Interior…, the differently colored beds signify, in fact, those of contagious patients.

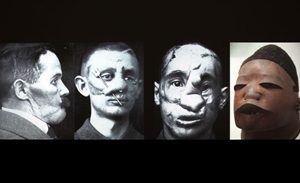

Fig. 4: Masks L. P. 1917, gelatin silver-print, National Archives, 398AP/41.

In this regard, much can be said about the kinship between the soldiers and the sick, the sick and the wounded, the disfigured soldiers as they are then represented, most notably by dadaism. The death of Guillaume Apollinaire from influenza in November 1918 was widely discussed in Dada circles, which defined itself as a “virgin microbe” infiltrating everywhere 10T. Tzara, « Conférence sur Dada », The meeting of constructivists and dadaists in Weimar, September 1922. I am grateful to Cécile Bargues for the reference.. In this context, George Grosz paints The Funerals [Homage to Oskar Panizza] (c. 1917-1918), and this chaotic, absurd world, where a skeleton dances on a coffin, resembles T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922), where the sense of emptiness and isolation described by the poet, the atmosphere of death and illness, the hallucinations and nightmares, are analyzed by Elizabeth Outka through the lens of influenza and its effects on Eliot. As for Grosz, he would later admit to having painted “In a strange street, at night, an infernal procession of dehumanized figures, their faces reflecting alcohol, syphilis, the plague…” 11N. Wolf & U. Grosenick, Expressionism, Taschen, 2004, p. 42. The emphasis is my own..

Grosz’s fevered hell has much in common with the undead of Gance and Murnau, immersing us in the dark side of history. While the wounded represent the guilty conscience of victory, the sick remind us that the flu “is a monumental failure, completely out of place in the history of medicine” 12Freddy Vinet, La Grande Grippe. 1918. La pire épidémie du siècle, Éd. Vendémiaire, 2018.. The wounded disturb peace and reconstruction; the sick, like Murnau’s monster, disturb modernity. They are counter-rhythms, archaisms. And this is precisely what contributes to making their position in history, in memory, and even in art, untenable. With few exceptions, art, like society of the time, would not have managed this discomfort any better; it perhaps did not know how to, or could not, tell this story that, in truth, was neither tellable nor audible.

And then, there had already been so many deaths. Was there a need to add more, to burden the images with other bodies, other mass graves? In family albums, those who died of influenza are marked with a cross. Was there a need to continue their interrupted lives in another way, they who had fallen at the worst possible moment?

Fig. 5: In a field in Alberta, men wear masks during the « Spanish » flu, Autumn 1918, Canada.

The influenza raises the issue of its expression, of the visual communication of its experience, echoing Walter Benjamin’s reflection when he tried to think about the problem of transmitting a disaster, after he saw “mute people” returning from World War I 13Walter Benjamin, Le raconteur, followed by Commentaire by Daniel Payot, Circé, 2014.. Marcel Duchamp would cleverly subvert things in December 1919 thanks to his sense of humor: either a bit of fresh air from the French capital, pure for breathing, or, on the contrary, stale air, sealed in glass, carrying microbes and viruses. Air de Paris [50ccs of Paris], like a joke, was given to the New York collector Walter Arensberg, barely recovered from influenza. At that time, Duchamp had abandoned figuration, and with Air de Paris, he may have been acknowledging that the figure of the sick, that of the epidemic, were inevitably unrepresentable, inexpressible except in the unresolved form of an enigma 14D. Hopkins, « Marcel Duchamp’s Paris Air. The ‘Spanish Flu’, Black Humour, and Dada Contagion », in David Hopkins, Disa Persson (ed. by), Contagion, Hygiene, and the European Avant-Garde, New York, Routledge, pp. 119-136..

And, after all, what could one really represent? Susan Sontag reminded us that striking diseases —and thus those that can be represented—are the ones that disfigure, provoke collective hysteria, and lead to the stigmatization of the sick15D. Hopkins, « Marcel Duchamp’s Paris Air. The ‘Spanish Flu’, Black Humour, and Dada Contagion », in David Hopkins, Disa Persson (ed. by), Contagion, Hygiene, and the European Avant-Garde, New York, Routledge, pp. 119-136.. This, in turn, raises the question of events, in and of themselves, and in particular, about diseases “without imagination.” However, while the “Spanish flu” has visible symptoms, there is nothing particularly spectacular or stigmatizing about them—take, for example, Stieglitz’s Portrait of a sick Georgia O’Keeffe (1918), or Munch’s Self-portrait after his illness.

Fig. 6: Edvard Munch, Self-portrait with the Spanish Flu, 1919, oil on canvas, 59 × 73 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

As for Pablo Picasso, he almost mockingly portrays Jean Cocteau when the latter was ill, representing it in such a small way: there is “nothing” to see, especially since even the wearing of masks doesn’t seem to have captured the imagination of artists. Furthermore, influenza sufferers often died very quickly, making it difficult to depict them in the moment; the fear of contamination was strong, often preventing people from interacting with the sick…

This kind of absence and silence in the artistic images of the influenza is certainly a case study for art history. Their rarity nonetheless makes them privileged viewpoints of the epidemic event, allowing us to reflect on its disruptive nature, even in art. It forces us to move beyond the obvious and stereotypical forms of illness to consider other images, who might tell the story in a different way. We could then acknowledge their active role—despite everything—based on their ability to capture the stakes of this major health crisis and give it form, however few those forms may be.

Notes

[1] Anne Rasmussen, in an interview with Florence Rosier, Le Temps, November 2018.

[2] For the poster for the 49th Vienna Secession Exhibition in 1918.[3] A.-M. Mercier-Faivre & C. Thomas, éd. by, L’Invention de la catastrophe au XVIIIe siècle. Du châtiment divin au désastre naturel, Droz, 2008, p. 28.

[4] A. Camus, La Peste, Gallimard, 2012, p. 48.

[5] G. Didi-Huberman, L’humanisme altéré. La ressemblance inquiète, I, Gallimard, 2023, p. 95.

[6] E. Outka, Viral Modernism. The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature, Columbia University Press, 2020.

[7] J. Giono, « Arcadie ! Arcadie ! », January 1953, in Provence, Gallimard, 1993, p. 134.

[8] See C. Einstein, « La discontinuité même », in La discontinuité même, l’écarquillé, 2021.

[9] Arthur Conan Doyle, in 1921, quoted by Laura Spinney in La Grande Tueuse. Comment la grippe espagnole a changé le monde, Albin Michel, 2018, p. 307.

[10] T. Tzara, « Conférence sur Dada », The meeting of constructivists and dadaists in Weimar, September 1922. I am grateful to Cécile Bargues for the reference.

[11] N. Wolf & U. Grosenick, Expressionism, Taschen, 2004, p. 42. The emphasis is my own.

[12] Freddy Vinet, La Grande Grippe. 1918. La pire épidémie du siècle, Éd. Vendémiaire, 2018.

[13] Walter Benjamin, Le raconteur, followed by Commentaire by Daniel Payot, Circé, 2014.

[14] D. Hopkins, « Marcel Duchamp’s Paris Air. The ‘Spanish Flu’, Black Humour, and Dada Contagion », in David Hopkins, Disa Persson (ed. by), Contagion, Hygiene, and the European Avant-Garde, New York, Routledge, pp. 119-136.

[15] Susan Sontag, La maladie comme métaphore ; Le sida et ses métaphores, & Œuvres complètes, III, Christian Bourgois Éditeur, 2009, pp. 163-166.

Thibault Boulvain is Assistant Professor in Art History at Sciences Po. He is the co-convenor, with Laurence Bertrand Dorléac, of the seminar “Arts et Sociétiés”. He is the author of numerous texts, including Art in the Time of AIDS: 1981–1997, published in June 2021 by the Presses du reel, which was awarded the Lucie and Olga Fradiss Foundation Prize in 2022.

In line with his previous research, he is currently focusing on artistic and visual representations of the “Spanish flu,” as well as, more broadly, on depictions of illness from Antiquity to the present day. He is also currently researching “the ‘Mediterranean effect’ in art from the Second World War to the present.