Beyond Cogito: all Sciences Po urban research and courses

27 September 2017

The 1970s: the European left and globalization

30 September 2017Côme Salvaire, a PhD student at Sciences Po’s Center for International relations, has devoted his thesis to the architecture of urban political organizations through the prism of waste management, with a focus on Lagos and Mexico. Here is an overview of his initial research on waste management in Lagos.

The environment, an area of urban empowerment

Today, cities are at the forefront of the fight against environmental degradation. In reaction to states that they portray as excessively static, major cities are asserting their capacity to act in the environmental area, to the point of shaking up the national level. Organized into networks, such as C40 Cities, they invoke the emergence of an interurban diplomacy that is capable of producing more reactive and ambitious environmental cooperation than international treaties, in a departure from nation-state diplomacy. For the mayors and governors of metropolises, climate change management appears to have created opportunities to claim greater independence from states.

Today, cities are at the forefront of the fight against environmental degradation. In reaction to states that they portray as excessively static, major cities are asserting their capacity to act in the environmental area, to the point of shaking up the national level. Organized into networks, such as C40 Cities, they invoke the emergence of an interurban diplomacy that is capable of producing more reactive and ambitious environmental cooperation than international treaties, in a departure from nation-state diplomacy. For the mayors and governors of metropolises, climate change management appears to have created opportunities to claim greater independence from states.

Environmental policy: a driver of de-politicization?

Décharge informelle à Mushin, Lagos. Crédits : Côme Salvaire

However, the inclusion of major global cities in global environmental agreements has raised a major issue in urban research. Many researchers have noted the de-politicizing effect of environmental constraints at the urban level. Is the “green” imperative helping to establish a new form of environmental engineering impervious to debate and political contestation within the cities? As public action on the environment drives the strengthening and independence of urban government, what actors and social groups are benefitting? What are the effects on the political structures of metropolises?

Population growth and a new “political” architecture

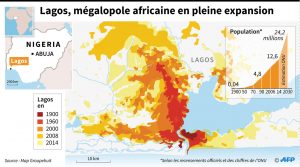

Nigeria’s economic capital Lagos has become Sub-Saharan Africa’s most populated megalopolis and a particularly interesting urban laboratory, especially with regard to waste management. Since experiencing rapid urbanization in the 1980s, followed by a drastic decline in urban services, Lagos and its fourteen million residents have run up against a new environmental limitation that brought the urban fabric to saturation at the turn of the millennium. The development of waste management infrastructure over the past ten years has been accompanied by the transformation of institutional and political structures in Lagos.

Nigeria’s economic capital Lagos has become Sub-Saharan Africa’s most populated megalopolis and a particularly interesting urban laboratory, especially with regard to waste management. Since experiencing rapid urbanization in the 1980s, followed by a drastic decline in urban services, Lagos and its fourteen million residents have run up against a new environmental limitation that brought the urban fabric to saturation at the turn of the millennium. The development of waste management infrastructure over the past ten years has been accompanied by the transformation of institutional and political structures in Lagos.

New tools, new powers

Chiffonniers au travail à Olushosun (Lagos) la plus grande décharge d’Afrique. Crédits : Côme Salvaire

The establishment of a new chain of actors to organize the circulation of waste in the city began in 2005, drawing on the use of new political tools (regulations and taxation) that deeply transformed the political scene of this African metropolis.To the extent that the regulations and new taxation tools made it more difficult for waste to be picked up by informal collectors, who themselves were generating informal income captured by local politicians and field officers, the waste management network became a powerful technical ally for other actors at the metropolitan level.

The infrastructure opened new opportunities for spatial control (organization of waste flows and reorganization of spaces to enable collection) that contrasted with the territorial control mode in place since the 1980s, which had aimed to control each neighborhood through integration into patronage networks. Powerful actors, beginning with the State of Lagos, created and exploited the opportunities offered by spatial control. The local elite that had traditionally been at the heart of the territorial control of the city’s neighborhoods moved closer to the political center to fully capitalize on the control methods provided by the waste management infrastructure.

“Clean” management as an exclusionary tool

The power struggle around waste has had major implications for the lives of residents, especially in the most marginalized neighborhoods. Lacking the resources needed to adapt to the spatial control methods created by the infrastructure, and unable to “connect” to the infrastructure, these neighborhoods found themselves in a precarious position vis-à-vis the political center. Thus, in November 2016 the governor called for the destruction of neighborhoods built on stilts over the lagoon, where over 300,000 people live. Several tens of thousands residents have already been driven out of their homes. These destructions have largely been justified on environmental grounds.

An uncertain future

Thus, waste provides a window into the transformations of power relations in urban societies. While it may appear to be a neutral subject, waste is a crucial political “ally” in the formation of urban governments. Furthermore, the case of Lagos shows that once climate and geological pressures are cast into political opportunities, they can transform the local political scene and are likely to deepen exclusionary forces in major cities.

Read more

“It’s like a civil war”: in Lagos, land clearances can be fatal by Côme Salvaire and Charlie Mitchell, Citymetrics, o CityMetric, Dec. 2016