De-risking European supply chains

16 June 2025

The Just Transition Mechanism: Making Sure No One Is Left Behind

24 June 2025Driving Change: Strategies for Policy Innovation and Implementation

By Aniya GRILLO RICCELLI, Ilham CORADIDI, Eva FERRER CORRAL, Marti SERRA FIGAROLA and Carolina LEON SANTIAGO

Introduction

As the world becomes increasingly complex and interconnected, so do the challenges we face. Issues such as climate change, the 2008 financial crisis, and COVID-19 have demonstrated that many modern challenges are deeply intertwined, systemic, and transcend national borders. In this context, traditional policies that target specific issues in isolation often fail to address broader interdependencies, highlighting the need for transformation policies—policies designed to tackle grand challenges by reconfiguring entire systems.

This blog contribution aims to review and explore one of the main responses given to all these challenges: transformation policies. This type of policies have emerged as a response to these complex, systemic global challenges, that require a fundamental rethinking of how societies organize their economies, technologies, and institutions. They are defined as a broad framework for addressing large-scale societal and environmental challenges through profound changes in existing socio-technical systems. Unlike traditional policies, transformation policies take a comprehensive and often experimental approach. They include political and social reforms and rely on strategies that engage multiple stakeholders. Given their innovative nature and its central role in achieving not only decarbonisation, but a transition to a more just society, it is crucial to understand how transformation policies are researched and deployed, and to what extent their development differs from classical policy-making approaches.

The academic literature on transformation policies has grown significantly in recent years, reflecting a heightened awareness of this policy shift in academia. Scholars have highlighted the necessity of such policies in fields like climate action, framing them as the only viable societal response to current and projected environmental challenges and broader sustainability goals. Unlike incremental adaptation strategies—which introduce small changes while sustaining the existing system’s functioning—transformation policies aim for deep, broad, and timely systemic changes. These policies are designed to match the urgency and scale of the challenges they address.

This novel mode of governance requires a fundamental shift in how policies are researched and implemented. Transformation policies challenge prior assumptions and demand an openness to iterative learning. Haddad and al. identify several key characteristics that define transformative innovation policies. These policies focus on grand challenges, addressing a broad spectrum of critical issues such as climate change, aging populations, environmental degradation, and public health. They emphasize socio-technical transitions, combining social transformation with technical innovation to achieve systemic change. Furthermore, transformation policies rely on multi-faceted policy instruments, moving away from the traditional “one objective, one policy” framework by employing a broad policy mix that integrates previous strategies into a new paradigm and destabilizes outdated systems. Their implementation necessitates the involvement of multiple actors and networks, engaging diverse stakeholders across various sectors and levels. Additionally, a multi-level governance approach is essential, coordinating efforts at local, national, and international levels to address systemic challenges comprehensively.

In this contribution, transformation policies have been identified as one of the main instruments that rethink traditional approaches. While embracing this innovative framework, it is necessary to pursue the shift in governance required to tackle the complexity and urgency of today’s global challenges, transformation policies have clear limits that need to be addressed and understood. This blog contributes to their understanding in the areas of research and deployment by an exhaustive analysis of the problems that arise and two case studies: Singapore Green Mark Scheme and UAE’s Masdar City.

Research of Transformative Policies

If TIPs are such comprehensive policies whose objective is to disrupt established path dependencies, a key question arises: how can they be effectively developed? That is, how can one research the background elements and design the appropriate policy instruments to cope with uncertainty; to cope with change towards the unknown? Can transformation be predicted through research or can we only give it impulse without clearly knowing in which direction it is going to follow? And, perhaps more importantly, there is the question of evaluation and the capacity that we have to reflect on enduring transformative policies to provoke a feedback loop that helps us improve the current implementation.

To better address these questions, we need to come back both to the history of frameworks of innovation and the classical characterisation of the policy cycle. Schot and Steinmueller have identified three main frames for innovation policy that have also evolved in history. Initially, they identify the emergence of the “innovation growth” frame after WWII, which highlighted the importance of investment in R&D to cause innovation that, in turn, would provoke long term growth. Secondly, they identify the emergence of the “national systems of innovation” frame during the 80s, which starts to put emphasis on public policy-making to enhance the national innovation systems in order to push innovation. This frame assumes a bigger role of the state in easing the institution’s relations and the transfer of knowledge. Finally, we find the “transformative change frame”, under which TIPs fall. This framework requires new network relations and different policies to address comprehensive systemic problems. Looking at the classical policy cycle,we can see how each step changes its traditional character when analysing a TIP. For this blogpost, we will focus specifically on “Agenda setting”, “ Policy formulation”, “Evaluation” and “Policy learning” as proxies for “research in TIPs” and, in the next section, “Implementation”.

Figure 1. The generic policy cycle. From Haddad et. al. (2022).

In this framework, agenda setting is the first step of the policy cycle and it is tasked with the agenda-setting of the objectives of the intervention. To do so in transformative policies is especially challenging because of their multiplicity: reduce inequality, reduce GHG emissions, transform the mobility system etc. Grand challenges bring together economic, societal and environmental objectives, and bring up a trade-off between the effectiveness of the objectives and their narrowness across multiple economic sectors. To set these objectives, we will need the use of multiple foresight techniques to establish the potential futures and the desired effect of the intervention. Policy formulation is the phase that succeeds the agenda setting and is tasked of designing the policy instruments necessary to achieve the objectives. This phase requires a great deal of research to address the puzzle between the objectives, the available resources and the policy mix to have actionable processes. This requires the need to evaluate different paths and its outcomes. For TIPs, however, the policy design is not a cost-benefit analysis. Rather, it needs to be an iterative and experimental approach that should enable niche experimentation and re-definition of the policy design. For this however, the evaluation programs and learning loops need to be designed ex-ante to be able to produce a back and forth process. Authors learning from the planning of previous national strategies have identified best practices in harmonising common reporting framework or establishing better monitoring systems.

Finally, TIPs also require a different approach to evaluation. This phase is tasked both if the identified objectives were beneficial and if the policy was correctly implemented and designed. The characteristics of TIPs make evaluation extremely challenging to evaluate: who evaluates, when and how? Which indicators can be used? And, maybe more problematic, are discrete indicators able to capture systemic transformations? Evaluation of TIPs should be a challenge for public policy scholars. Its radical and fundamental uncertainty as well as its comprehensive character call for systemic indicators and general systems of evaluation rather than the tracking of concrete indicators. Some potential solutions are the aforementioned formative approach to evaluation, with the involvement of stakeholders and a continuous reflexive change on the policy design.

Deployment Strategy

During the IPCC 5th assessment report, the definition of “transformation” has created both an awareness of the importance of transformation policies and confusion about the concepts of change and how it can be applied in policy and practice.

Change is defined by most authors as a “fundamental alteration of state”. Usually, change in systems proceeds incrementally, involving piecemeal adjustment (theory by Sir K. Poppers) of technologies and societal practices. Here, transformation implies something “more significant”, closer to a directional shift.

The main challenge for deploying transformation policies is to avoid path dependency and development as-usual. Even when decision-making spheres are aware of the risk of path dependency when formulating policy actions, other risks might emerge: relying on technological and research innovation only, creating a ‘technocratic transformation’ that does not serve as a sustainable foundation for societal transformation ; institutional levels limiting the scale-up and improvement of industries and societal mechanisms because of pre-existing structural siloes or procedural bottlenecks ; a transformation policy that does not effectively combine incremental changes with deeper intervention in order to disrupt the status quo and create system-wide change.

The needed policy mix for effectively deploying transformation policies will affect the three pillars of sustainable developments in the society: the social, by reorganising links between individuals and groups, and deep-seated governance structure; the economy, by creating new fundings schemes and portfolios with the creation of financial incentives to invest and participate in transformation policies; and the protection of the environment and the human surroundings.The latter is both an issue in itself and the link between the social and economic aspects of transformation policies. Because they affect all aspects of society, transformation policies must promote livable, fair, and viable changes.

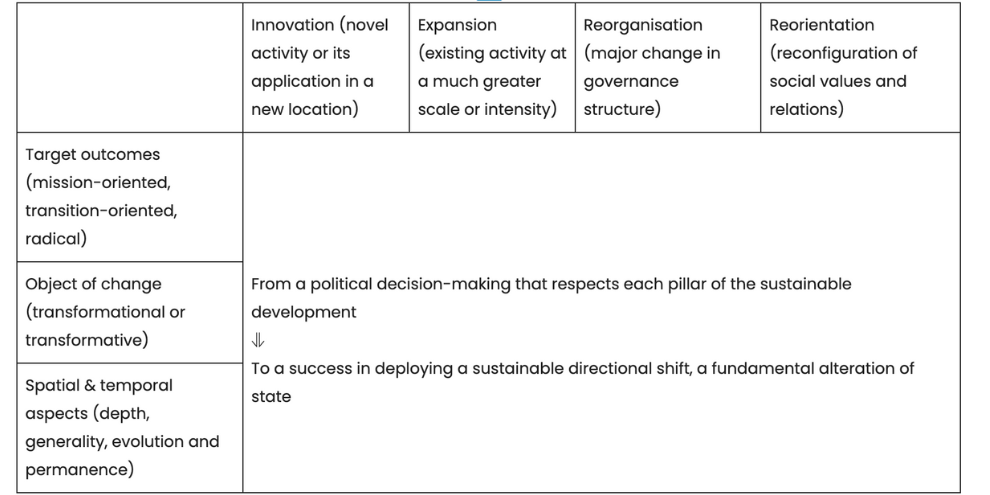

In the formulation of policy actions, a “typology of changes” should serve as a base for the transformation process (see Annex 1). Transformations are either those adopted at a much larger scale or intensity, or those that are truly new to a particular region or resource system, and finally those that transform places and shift locations. Classification aspects such as the target outcomes, the object of change and the spatial and temporal dimensions are to be considered when taking policy actions.

Transformations resources

Firstly, transformation policies must efficiently allocate resources, whether human or financial. Financial resources must be gathered and allocated in an agile manner. For example in the European framework, the Draghi Report emphasises on a better flexibility between private and public investments, a flexibility that should be possible if the private sector is stimulated enough by the public sector. National Promotional Banks and Institutions (NPBIs) could be drivers of higher risk investments for the private sector to couple research and innovation, drivers of productivity according to the former President of the European Central Bank. Here, governance arrangements are crucial and therefore require institutional quality.

Transformation relations

Secondly, to achieve sustainable societal transformation, it is crucial to emphasize the diversity of opinion and involve a broader set of actors than traditional development models. This approach requires engaging multiple actors and creating global networks that span the public, private, and non-profit sectors, as well as different parts of government and international levels. By picking the willing and ensuring the involvement of diverse stakeholders, transformation policies can address the structural relationships between societal groups and institutions, fostering more inclusive and effective change.

Example of successful policies : Singapore GMS and Masdar City (UAE)

Urbanization has accelerated globally, with over 50% of the world’s population in cities today, projected to reach 85% by 2100. This trend makes cities crucial for addressing social, economic, and environmental challenges when they are responsible for 70% of greenhouse gas emissions.Advanced economies have therefore adopted green buildings (GB) policies; it is the case of Singapore and Abu Dhabi which both have developed successful transformative policies to mitigate sustainability and habitat. The former adopted in 2005 the Green Mark Scheme (GMS) which classifies GB “greenness” and gives guidelines for the construction industry, while the latter is what we called an eco-city. Launched in 2006, Masdar-City serves as a global example of a sustainable city.

Three factors contributed to the GMS success. First, the government provided legal aid through the Green Building Product Certification to assess building products and materials and set benchmarks for their environmental sustainability level. Secondly, it provided financial incentives to persuade industries into believing that going green was viable ($20M Green Mark Incentive Scheme for New Buildings) and managed to engage multiple stakeholders in effective green building operation through urbanization campaigns. As a result, Singapore-based CapitaLand, Southeast Asia’s largest developer, says investments in green-building technologies have helped the company reduce 11.7% of its energy consumption and 16% reduction in carbon emissions between 2008 and 2013.

Similarly, Masdar city as a global policy statement from the UAE, is organized around four key areas. With an objective of 40% reduction in the energy consumption of its buildings and 40% reduction in the use of interior water, it has developed a two-fold energy and water management approach including: efficient energy generation using novel techniques (photovoltaic panels, window-glazing etc.) as well as improved efficiency of wastewater treatment and processing methods. The results were effective. Generally speaking, from 2009 to 2019, this has helped in reducing 60% water consumption by every square meter compared to the usual consumption conditions. Moreover, the dormitory buildings in the campus of Masdar Institute reduced their electricity consumption by 51% and their energy used in heating water by 85% compared to the average level in the UAE, bringing the city on the road to a sustainable city in light of transformation policies.

Challenges and Barriers

It goes without saying that challenges and barriers will come along the way when discussing TPs as they are grand challenges we are trying to overcome.

In the first place, it is to mention the prejudices and fears of actors involved in the funding procedure of such policies, as it is new systems they are trying to introduce and there is an intrinsic component of unpredictability or unknown in comparison to classical non-transformative and systemic policies. This fear by itself can negatively impact the social and economical perception of such measures, resulting in underfunding and its consequent improper development.

In addition to these social perceptions, there are challenges in the implementation cycle, as there can be a lock-in effect or social backlash.

In the first place, we refer to a lock-in effect when there is a vested interest growing attached to the large amounts of investment in the infrastructure process, which go against the core of system transformation, resulting in an unsuccessful pathway.

Because of its quasi-experimental character, there is also a probability of unsuccess – as within any other policy-making process. Yet this one carries a strong social factor where the initial diffusion success can be re-inverted and provoke a backlash effect amongst the participating actors. As an example, we can take the case of the Barcelona “superilles”, which was a project launched by Ada Colau, former mayor of Barcelona, where they established a new organizational structure and dynamics of certain neighbourhoods of the city, reshaping the city blocks, being a case of a system transformation. Nevertheless, backlash seemed inevitable and multiple protests were amplified by extreme-right parties and associations as not all the outcomes seemed to benefit the whole of the city.

However, there are even more challenges in the own making of the TPs, ranging from its drafting procedure to the implementation of them with the stakeholders.

Firstly, there is a need of reconciling different perceptions of innovation to address wicked problems (1), which adds up to the lack of translation of societal goals into such policies in order to add social benefits (2), a task which is rather complicated to fulfill given the need to coordinate multiple policy domains and levels (3) as we need to establish more characteristics to attribute policy effects (4), where there is a lack of evaluation practices for assessing policy-mixes and transformative policies indicators. In the stakeholders fields, we see the challenge of empowering broader stakeholders(5), balancing influence from groups of interests (6) to avoid the aforementioned lock-in-effect, given a possible rise of power struggles and conflicts of interest (7). In general terms, there is also the challenge of overcoming past policy dependencies (8) and improving the governance and institutional capacity involvement (9).

On a final note, we can question our own academic challenges, as normative validity and legitimation in the making of policies involve a socio-cultural acceptance that is translated into our frameworks, rooted in our internal standards, where we can put to the test our ability to think outside the box and overcome a normative validity which might limit our academic standards.

Conclusion

In conclusion, transformative innovation policies represent a crucial shift in the governance needed to address the complexity and urgency of contemporary global challenges. Moving beyond traditional, incremental approaches to policy making, transformative innovation policies embrace systems thinking, multi-level governance and experimental strategies to tackle major challenges such as climate change, social inequality and urban sustainability.

This blog has highlighted both the potential and the limitations of TIPs. On the one hand, the examples of Singapore’s Green Mark scheme and Masdar City in the United Arab Emirates demonstrate that well-designed TIPs can deliver significant social and environmental benefits. On the other hand, the obstacles to their implementation, such as path dependencies, institutional silos and social resistance, underline the need for continuous learning, strong stakeholder engagement and innovative evaluation methods.

As societies face increasingly interconnected challenges, the role of TIPs in systemic transformation will only grow in importance. However, their success depends on their ability to overcome inherent uncertainties and foster collaboration across sectors and scales. By rethinking the way in which policies are studied, developed and implemented, TIPs offer a promising framework for creating a more sustainable, equitable and resilient future.

Annexes

Annex 1 – Typology of changes

References

Berglund, O., Dunlop, C. A., Koebele, E. A., & Weible, C. M. (2022). Transformational change through public policy. Policy & Politics, 50(3), 302-322.

De la Peña, D. (2016, November 23). Superilles. David de la Peña Blog. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from https://daviddelapena.com/2016/11/23/superilles/

Douglass, M. (2016). The rise of progressive cities in Asia: Toward human flourishing in Asia’s urban transition. Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. Working Paper Series No. 248.

Feola, G. (2015). Societal transformation in response to global environmental change: A review of emerging concepts. Ambio, 44(5), 376-390.

Gillard, R., Gouldson, A., Paavola, J., & Van Alstine, J. (2016). Transformational responses to climate change: beyond a systems perspective of social change in mitigation and adaptation. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 7(2), 251-265.

Griffiths, S., & Sovacool, B. K. (2020). Rethinking the future low-carbon city: Carbon neutrality, green design, and sustainability tensions in the making of Masdar City. Energy Research & Social Science, 62.

Haddad, C. R., Nakić, V., Bergek, A., & Hellsmark, H. (2022). Transformative innovation policy: A systematic review. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 43, 14-40.

Haddad, C. R., Nakić, V., Bergek, A., & Hellsmark, H. (2022). Transformative innovation policy: A systematic review. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 43, 14-40.

Han, H. (2018). Governance for green urbanisation: Lessons from Singapore’s green building certification scheme. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 37(1).

Ives, M. (2013). Singapore takes the lead in green building in Asia. Yale Environment 360. Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies.

Jakob Edler, Katrin Ostertag, Johanna Schuler, Social innovation, transformation, and public policy: towards a conceptualization and critical appraisal, Science and Public Policy, Volume 51, Issue 1, February 2024, Pages 80–88,

Kates, R. W., Travis, W. R., & Wilbanks, T. J. (2012). Transformational adaptation when incremental adaptations to climate change are insufficient. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(19), 7156-7161.

Kaur, M. J., & Maheshwari, P. (2016). Building smart cities applications using IoT and cloud-based architectures. In Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE International Conference on Industrial Informatics and Computer Systems, American University in Sharjah, March 13–15.

Kumar, N., Gupta, S., Tyagi, A., Bhushan, B., & Joshi, A. (2022). Smart cities and environmental sustainability: Applications of AI and IoT. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 27, 101724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2022.101724

Lavell, A., Oppenheimer, M., Diop, C., Hess, J., Lempert, R., Li, J., & Myeong, S. (2012). Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. A special report of working groups I and II of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (IPCC), 3, 25-64.

M. Draghi, European Commission. (2024). 3. Sustaining investment. EU competitiveness: Looking ahead. Retrieved from https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en

Myllylä, S., & Kuvaja, K. (2005). Societal premises for sustainable development in large southern cities. Global Environmental Change Part A, 15, 224–237.

Nalau, J., & Handmer, J. (2015). When is transformation a viable policy alternative?. Environmental science & policy, 54, 349-356.

O’Brien, K. (2012). Global environmental change II: From adaptation to deliberate transformation. Progress in human geography, 36(5), 667-676.

Olsson, P., Galaz, V., & Boonstra, W. J. (2014). Sustainability transformations: a resilience perspective. Ecology and society, 19(4).

Ostojic, D. R., Bose, R. K., Krambeck, H., et al. (2013). Energizing green cities in Southeast Asia: Applying sustainable urban energy and emissions planning. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

Park, S., Howden, M., & Crimp, S. (2012). Informing regional level policy development and actions for increased adaptive capacity in rural livelihoods. Environmental Science & Policy, 15(1), 23-37.

Park, S., Howden, M., & Crimp, S. (2012). Informing regional level policy development and actions for increased adaptive capacity in rural livelihoods. Environmental Science & Policy, 15(1), 23-37.

Pelling, M. (2010). Adaptation to climate change: from resilience to transformation. Routledge.

Pelling, M., O’Brien, K., & Matyas, D. (2015). Adaptation and transformation. Climatic change, 133, 113-127.

Sandberg, M., Klockars, K., & Wilén, K. (2019). Green growth or degrowth? Assessing the normative justifications for environmental sustainability and economic growth through critical social theory. Journal of Cleaner Production, 206, 133-141.

Sankaran, V., & Chopra, A. (2020). J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1706.

Termeer, C. J., & Nooteboom, S. G. (2012). Complexity leadership for sustainable regional innovations. In Leadership and change in sustainable regional development (pp. 234-251). Routledge.Wise, R. M., Fazey, I., Smith, M. S., Park, S. E., Eakin, H. C., Van Garderen, E. A., & Campbell, B. (2014). Reconceptualising adaptation to climate change as part of pathways of change and response. Global environmental change, 28, 325-336.