Discussion highlights: Chair and Students Roundtable #2

24 November 2021

Reconciling climate policy and justice through domestic tradable carbon quotas

26 November 2021By Damien Turlay

This essay is one of the winners of the Fall 2021 Chair’s Essay Competition on the topic of: “What cause do you think Europe should mobilize around next?”

From the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 to the European Union in 1992, the European project has had one core mandate, one for which it received a prize recognising its effort and overall success: the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize. Internal European conflicts have shaped World Wars in the past century and now seem a rather inconceivable thing. Nonetheless, if one was to ask for a new mandate for the European Union, I do not believe it would be much different than what it was.

After making war materialistically impossible through common markets for steel and coal, long-lasting peace was built, achieved and sustained through economic prosperity. A supranational entity such as the European Union, preceded by the European Economic Community, would provide for bigger markets, better movement of workforce and capital, more opportunities and more wealth-creation leading to more stability and less conflicts. Growth in both the aggregate economy and individual standards of living were keys to peaceful, prosperous and just democracies. But are they still? Indeed, the very components of past intra and intercountry stability -with which it has borne much success- seem now to be much different and proteiform. In the face of climate change and biodiversity loss, a key component to peace will be resilience.

The efficiency of yesterday

European free trade foundations were built to, or subsequently ended up promoting, ricardian terms of deals: I produce all the wine, which I am much better for, and you produce all the tomatoes, for which my advantage exists, but is lesser than for the wine. This is built on the same flawed logic as most of environmental economics are: capitals are endlessly substitutable. I have too much wine and will use this excess to buy tomatoes. If I damage the environment or overuse natural resources, I will pay for it, with money. Wine then turns into tomatoes and financial capital turns into ecosystem services. The free European markets as well as EU’s penchant for international trade agreements led to a more “efficient” value creation and supply chain, but only efficient in its use of capital. It became much more complex, interconnected, energy and natural resource intensive. Pecuniary efficiency has therefore been traded at the expense of systemic resilience (Filion, 2013).

The more mitigation we do, the less adaptation will be required and the less suffering there will be ~ John Holdren, Science and Technology advisor to Barack Obama.

In the fight against climate change, what we don’t do in mitigation, we will do in adaptation. What we don’t do in adaptation we will do in suffering. Despite the sluggish application of Holdren’s vision by its member states, current EU governance seems to have well understood the importance, inevitability and somewhat urgency of mitigation. This translates into reduction in greenhouse gases emissions and net land-conversion as currently advocated for at COP26. Mitigation done, the forefront for not turning adaptation into suffering is resilience.

Addressing resilience can only lead to further questions: what is it, in the face of what do we want to be resilient, on what terms and more essentially, what for? Resilience is a concept well-known in engineering as well as human psychology which can be further applied to any system when studying its behaviour. By system, we can understand the world economy as well as the Earth-system, or even the very socio-economic structures of our societies. The “modern world” and its extensive stocks, flows and interconnections is a system on its own, one that many researchers have tried to simulate with models in the likes of World3 by MIT researchers (Meadows & al., 1972) or HANDY by NASA (Motesharrei & al., 2014). Questions such models are trying to answer are: how can a constraint or abrupt event compromise the functioning of the system the model is trying to represent? What is the proportion of, and to what extent, said system is to retrieve its original state after a shock? The most interesting use case of systems dynamic for our modern world is that the shock, or the constraint, is believed to be endogenous, not exogenous. As Ulrich Beck (1992) depicts it, we now live in risk societies: societies for which the threat they live under come from their very own structures and functioning, not from outside forces. All anthropogenic consequences are endogenous disturbances of our system. Resilience is the study of the consequences of all disturbances but the probable shift in the Anthropocene (Zalasiewicz & al., 2011) leads us to focus on what endogenous forces will do to the system when driven forward by the inevitable passage of time.

In that sense, some believe the global free-market based economy is the most robust and resilient system the human has ever built, or ever seen built on the face of the earth. The Great Depression, World Wars, the Global Financial Crisis and now the Covid-19 pandemic: all have hit the economy hard only to see it rise again in a rather similar fashion only months or years after the initial shock. The threat is now indeed that our economy’s resilience seems much greater than that of any other structures and systems we rely on. Whether it be ecosystems, earth’s biogeochemical cycles, welfare systems, or even democratic processes, they are all under high scrutiny for being more and more fragile as political willingness continues to portray our economy as the system to protect in the face of extreme events. All that, lowering future capacity to provide for basic needs as well as hopeful narratives for the generations to come. Ecosystems and societal structures that had taken hundreds, thousands, and billions of years to build can all be severely damaged within hundreds of years if we focus on protecting the wrong system. In addition to being the first we decide to care for, our free-market based economy seems to be a much more resilient system than others it is now competing with, as well as the overall system it is part of. Polyani (1944) further argues that market forces will actively destroy any other system if left to its own devices.

What is the European Union to do about this?

First of all, the acknowledgment that the very premises on which we built our current world economy could be the one failing us is a must. It is the first step in building new societal narratives and the underlying international collaboration framework that will make such narratives plausible. Second of all, the European community is to take a deep look into the causes and consequences of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. The analysis of the causes are advocates for urgent climate-change and biodiversity-loss mitigation (Schmeller & al., 2020)while consequences should make us look at the structures of our supply chains for essential goods and services, hence advocating for more resilience (Ivanov & Dolgui, 2020). Early lack of PPE for healthcare workers, current gas price surge as well as the microchip shortage are mere examples suggesting that we should avoid relying on non-domestic production in anticipation of uncertain times. The latter currently have high consequences on the European production of carsbut the same dynamic in the food industry in the future could result in much more damaging outcomes for the population’s basic needs (Davis & al., 2021). Structures relying on a dense web of local producers, transformers and distributors will account for more robust and less energy intensive production as well as local economic prosperity. This could be at the expense of ricardian or even schumpeterian ideals but these theories of prosperity through extensive trade or innovation should be rethought in the wake of the massive energy and material consumption reduction western society is ought to face.

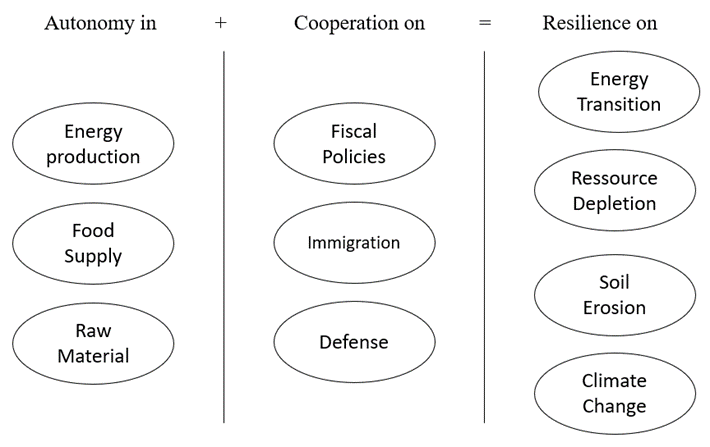

Ways to achieve resilience have been (Martin, 2019) and should further be extensively studied. It needs to be said it does not simply rely on food, energy, or even technological autonomy. Systemic resilience will require a high level of cooperation.

- Free circulation of capital implies that the financing of the transitions to come will require common fiscal policies in addition to the already common monetary policy. (Tabellini, 2016)

- Evolutions of flows of migration under the threat of climate change will require the UE to rethink and intensively cooperate on sound, human and efficient migration policies. (Geddes & Somerville, 2012)

- France’s recent diplomatic woes with Australia, the US and the UK also show that the EU should use its geographical and technological situation to become a major force in the military landscape, as advocated by the common defense project.

Fig: Resilience comes from degrees of autonomy and cooperation

Protectionism is not a threat to global wellbeing but a source of resilience

With the design of the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism, the World Trade Organisation should reconsider its aversion to protectionism and see it as a potential for trading the aforementioned capital efficiency for local resilience: it can turn out to be a source of social and environmental transfer instead of the dumping free trade currently allows, and sometimes promotes. It can also be a driver and incentive for local projects building a more socially just and environmentally friendly web of production and supply for essential needs. Preference for national, or at least continental, investment should not be considered as a frightened response to the threat of hardening foreign economic competition but a rather healthy tendency for less complex and transport intensive supply chains in the advent of increasing pressures from climate-change, biodiversity loss and all socio-economic consequences brought with it.

References

Filion, P. (2013). Fading Resilience? Creative Destruction, Neoliberalism and Mounting Risks. S.A.P.I.EN.S. Surveys and Perspectives Integrating Environment and Society, 6.1, Article 6.1. https://journals.openedition.org/sapiens/1523

Meadows, D. H., Randers, J., & Meadows, D. L. The Limits to Growth (1972). Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300188479-012

Motesharrei, S., Rivas, J., & Kalnay, E. (2014). Human and nature dynamics (HANDY) : Modeling inequality and use of resources in the collapse or sustainability of societies. Ecological Economics, 101, 90‑102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.02.014

Beck, P. U. (1992). Risk Society : Towards a New Modernity. SAGE.

Zalasiewicz, J., Williams, M., Haywood, A., & Ellis, M. (2011). The Anthropocene : A new epoch of geological time? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 369(1938), 835‑841. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0339

Polanyi, K. (1944). The Great Transformation : The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Beacon Press.

Schmeller, D. S., Courchamp, F., & Killeen, G. (2020). Biodiversity loss, emerging pathogens and human health risks. Biodiversity and Conservation, 29(11), 3095‑3102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-02021-6

Ivanov, D., & Dolgui, A. (2020). Viability of intertwined supply networks : Extending the supply chain resilience angles towards survivability. A position paper motivated by COVID-19 outbreak. International Journal of Production Research, 58(10), 2904‑2915. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1750727

Davis, K. F., Downs, S., & Gephart, J. A. (2021). Towards food supply chain resilience to environmental shocks. Nature Food, 2(1), 54‑65. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-00196-3

The High Price of Efficiency. (2019, janvier 1). Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/01/the-high-price-of-efficiency

Tabellini (2016). Building common fiscal policy in the Eurozone. Università Bocconi, CES-Ifo, CIFAR and CEPR. https://www.wiwi.uni-wuerzburg.de/fileadmin/12010030/2018/Rebooting_Europes_Monetary_Policy.pdf

Geddes, A., & Somerville, W. (2012). Migration and Environmental Change in International Governance : The Case of the European Union. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 30(6), 1015‑1028. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1249j