The horror and the glory: Bomber Command in British memories since 1945

This is a revised version of a paper originally prepared for the conference organized by Mass Violence & Resistance, Civilians at Stake: Mass Violence in Asia and Europe from 1931 to the Present, Paris, 16-18 December 2015.

Relative to most other European countries the United Kingdom enjoys a secure, positive memory of World War 2. At its simplest, the narrative goes: the Germans started it and the British, with their allies, won. However damaging to British relations with other European states since 1945, this account has proved remarkably durable1. Not for the British the ‘divided memory’ of Italy2 or the Vichy syndrome of France3 or the ‘historians’ dispute’ of Germany; Britain’s dominant memories of World War 2 are unified, straightforward, and patriotic.

Within this serene landscape, the combined bombing offensive against Germany, and specifically the part played by Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force (RAF), form an exception. Memories of Bomber Command are unusual in being both complex and volatile. They are complex because they concern inherently difficult questions – the effectiveness and the morality of strategic bombing in World War 2 – and because they have involved different ‘levels’ of memory –the official, the academic, the popular, the local – rather differently. A cohesive national myth of the bombing campaign, comparable (for example) to the British myth of the Blitz, the German bombing of British cities in 1940-19414, is impossible. Memories of the bombing offensive, moreover, are volatile because they have shown significant variance over time.

The nature of the offensive can be summarised in two sets of figures. First, approximately 125,000 men served as Bomber Command aircrew, 69.2 per cent of them British, the rest from Commonwealth or occupied European countries. Of these, 47,305 were killed in action or died while prisoners of war; a further 8,195 were killed in accidents; 8,403 returned home wounded; and 9,838, many of them also wounded, became prisoners of war. Thus 59 per cent of all who served became casualties, including 47 per cent killed5. As some of the most highly-trained men in the armed services, aircrew were well placed to know their chances; but all were volunteers.

More troubling, secondly, are the casualties that Bomber Command inflicted. The Allies dropped some 2.5 million tonnes of bombs on continental Europe, dwarfing the 75,000 tons dropped on the United Kingdom by the Luftwaffe. Just over half the total was aimed at Germany, one-fifth at France, and one-seventh at Italy6. Civilian deaths in Germany from Allied bombing were estimated at over 600,000 in the post-war decades. Even the more recent estimate of 380,000 remains very high7. To these should be added 60,000 or more Italian dead and a minimum of 57,000 for France8, plus several thousands for smaller countries including Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria and Bulgaria. Bomber Command dropped 53 per cent of the ordnance sent to Germany (against 47 per cent over Europe as a whole), and sought, through ‘area’ bombing, to destroy whole cities, not the precision targets aimed at, in theory, by the US Army Air Forces. Firestorms caused by Bomber Command’s incendiaries killed over 34,000 civilians in Hamburg in July 1943, 5,600 in Kassel in October 1943, at least 7,500 in Darmstadt in September 1944, 25,000 in Dresden and 17,600 in Pforzheim in February 1945 and 4,000-5,000 in Würzburg in March 1945: nearly 100,000 dead for the half-dozen deadliest raids9.

Bomber Command’s part in the offensive therefore involved exceptionally courageous young men burning to death thousands of civilian men, women and children. The first half of the equation is perfectly compatible with Britain’s master narrative of World War 2, the second emphatically not. The confusion was aggravated by the government’s failure at the time to tell the public that civilians were being deliberately targeted. Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command from 23 February 1942, sought a strong public statement of the objectives he had been invited to achieve: ‘the destruction of German cities, the killing of German workers and the disruption of civilized community life throughout Germany10.’ The Air Ministry, preferring to avoid controversy, refused.

The British media, quietly complicit with government, took the same line. However, fulsome press and radio coverage left the public in no doubt that there was a policy of ‘area bombing’ – attacking whole cities – and that it was causing, in the enthusiastic words of RAF spokesman and BBC commentator John Strachey, ‘destruction such as we in Britain never knew’. The death toll, though seldom estimated accurately, was never minimised. Yet the British public were also told that the Allied offensive was not only vastly more powerful than the German Blitz on Britain but vastly more moral, and that while the Luftwaffe sought to terrorise and kill civilians, the RAF did not11. The ambiguities involved have cast a long shadow, as Harris predicted when he warned that the Ministry’s refusal to acknowledge the true policy ‘will inevitably lead to deplorable controversies when the facts are fully and generally known’12.

The development of British memories of the bombing offensive since 1945 can be set roughly into three periods: relative quietism from the war until the early 1960s; two decades of scepticism from then until the early 1980s; and, since then, the slow growth of acceptance and memorialisation. However, these divisions are approximate and ragged, and, because memory operates at so many different levels, they are far from uniform.

At the extremes: the state, comics, and kits

Perhaps the starkest contrast appears at the extremes of the levels of memory that we have identified. At the summits of the state, the bombing campaign has been close to an embarrassment. For British boys growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, by contrast, it was celebrated in the new consumer products developed for the children’s market.

‘Most people’, observed Noble Frankland, one of the two official historians of the bombing campaign ‘were very pleased with Bomber Command during the war and until it was virtually won; then they turned around and said it wasn’t a very nice way to wage war13.’ His remarks apply perfectly to the British government. As early as 28 March 194514, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, in a note to the British Chiefs of Staff, attempted to disown the bombing policy he had hitherto backed and in particular the attack on Dresden six weeks earlier. Bomber Command was largely left out of celebrations of Victory in Europe; no specific Bomber Command medal was issued; Harris received no peerage or other honour from the Labour government elected on 26 July 1945. Harris’s own Despatch on War Operations was subjected to corrections by the Air Ministry, filed, and closed to the public for half a century15. The official British Bombing Survey completed in 1946, an altogether less ambitious project than its vast American counterpart, concluded that the British area attacks on German cities had been ‘undoubtedly overdone’; it too was left unpublished for half a century. The government did, it is true, authorise the publication of a big official history of the campaign, discussed in more detail below, in 1961; but it offered little comfort to those who wanted the bombing campaign rehabilitated16.

Official distance from the offensive is also reflected in policies of memorialisation. Battle of Britain Day, on 15 September, celebrates Fighter Command’s achievement in blocking the Luftwaffe’s offensive against the RAF; there is no Bomber Command equivalent. Public money financed neither the statue of Harris, unveiled in 1992, nor the Bomber Command memorial opened in Green Park, London twenty years later. Official reluctance to celebrate the bombing offensive may be explained by the distaste referred to by Frankland, and by the perceived need for good relations with the Federal Republic of Germany within the context of the Cold War and, from 1961, of Britain’s rapprochement with Europe. Hostile reactions in Cologne and other German cities to the unveiling of the Harris statue17 suggested that despite the involvement of the Royal Family in the opening ceremonies, governments had every reason to keep them at arm’s length.

‘Forgetting’, the title of the final chapter of Patrick Bishop’s popular history Bomber Boys, therefore appears accurate in relation to government18. Not so in the culture of schoolboys. They were treated, in the comics of the postwar generation and in the cheap and accurate plastic kits on sale from the 1950s, to a continuous celebration of World War 2 in which the bombing war played a prominent part.

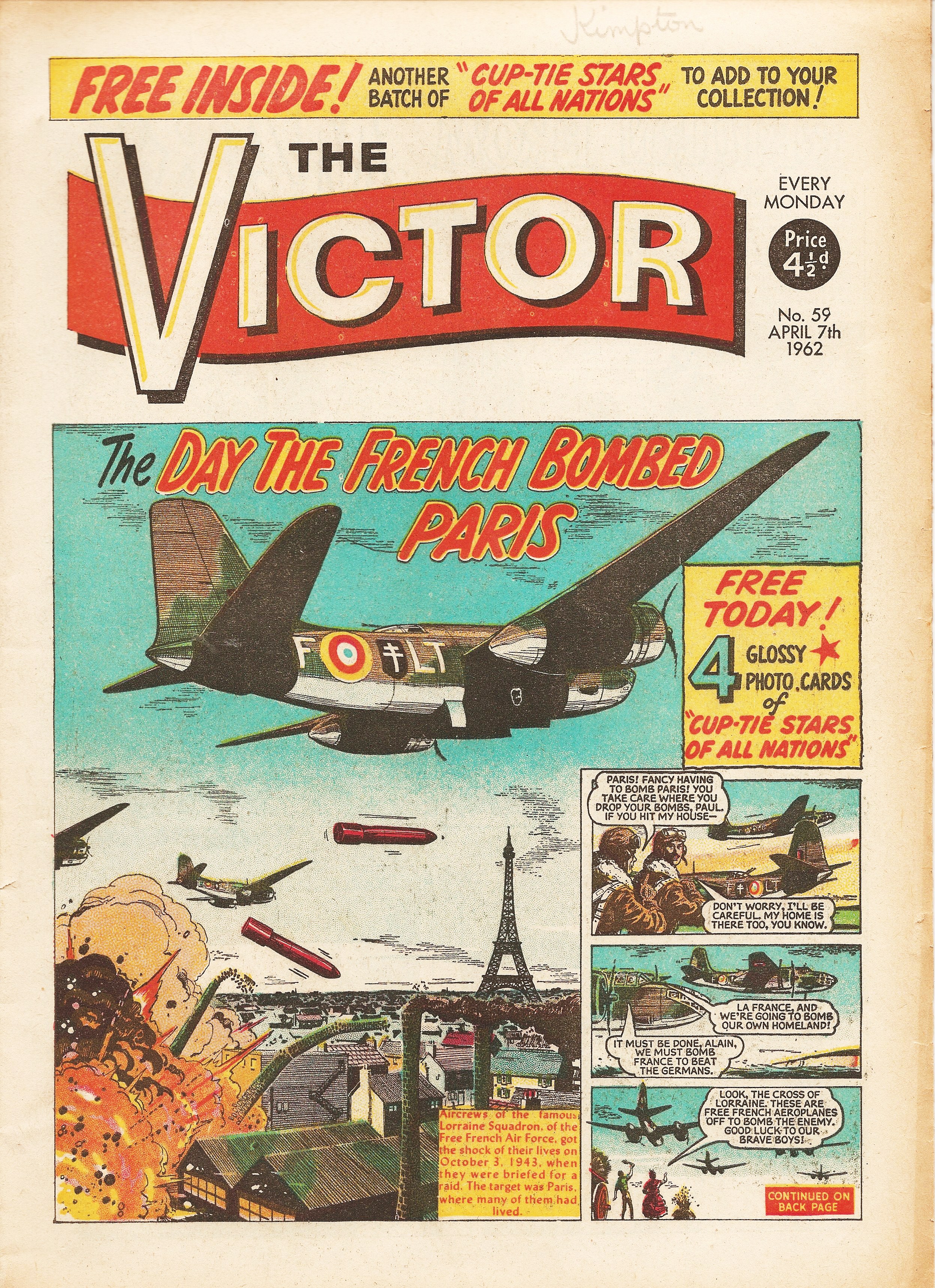

The British comic enjoyed a golden age in the 1950s, offering some 32 pages of strip cartoons to weekly readers. Some comics were humorous, others devoted to adventure and war. Longer war stories dominated the various twice-monthly, smaller-format series such as Thomson’s Commando comics or Fleetway’s Air Ace picture library. Some weeklies reached audiences of 2 million; Commando, which still appears, managed 750,000 annually in the 1970s19. One of the most successful weeklies, and the most dominated by World War 2 stories, was the Victor, which ran from 1961 till until 199220. A speciality of the Victor was the two-page ‘true story of men at war’ on the front and back covers, frequently ending with a heroic death, for example of Flying Officers Mansell over Cologne in May 1942 or Lamy after the Free French raid on Chevilly-Larue in October 194321.

The Victor also carried a long-running fictional series featuring ‘the greatest pilot of World War 2’, the bomber veteran Matt Braddock. ‘Memory’ in the comics is inevitably distorted. All raids target precise objectives, not whole cities. Every crew appears able and willing to fly a Lancaster into flak at 1,000 feet. Braddock and the other fictional flyers are aces who break rules and challenge authority; being grounded for indiscipline appears as great a danger as being shot down. And German civilians are invisible (as, it is true, they were to the aircrews)22.

From reading the Victor, war-minded boys could turn to models of the aircraft. The first Airfix kit aeroplane – unsurprisingly, a Spitfire – appeared in 1953; it would be followed, by the 1960s, by the full range of British and American medium and heavy bombers23. Airfix kits could be bought for pocket-money and at least the smaller ones could be assembled by a 7-year-old; young teenagers could graduate to carefully-painted, realistic models. And the tactile contact that a kit offered enhanced the fascination of the Lancasters and Fortresses, which – although obsolete by 1945 – were central to the attraction of flying stories for boys.

However much British governments might prefer to forget Bomber Command, then, a generation of post-war boys was invited to celebrate an idealised version of its achievements on paper and in plastic. Although competition from electronic entertainment had closed down most weekly comics by 2000 and damaged Airfix sales, both still appeal to a nostalgic older audience. The Commando picture library has survived, with two-thirds of its readers aged over 1524. The Victor brought out a 50th anniversary commemorative volume in 2010, including six Braddock stories and an introduction by famous special forces veteran Andy McNab25. The Airfix catalogue, meanwhile, offers a choice of five different Lancaster kits, including a Bomber Command set sold in aid of the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund26.

Bomber Command and the Historians

Between the two extremes of government and boys’ culture lie a significant academic historiography, popular history in the form of books, films and documentaries; and the outputs of actors in civil society, including churches, groups linked to the RAF and to veterans, and the right-wing press.

The historical studies were rapidly marked by two opposed viewpoints. The first, sceptical, analysis came in the 1946 Report of the British Bombing Survey Unit. Though not published until 1998, the BBSU’s report was influential both because many of its findings appeared to be confirmed by those of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS), and because significant parts of it were ‘carried forward into the work of the British Official History of the offensive27’ , published in 1961. The report was clear that the British area offensive had failed both to break German morale and to stem the rise in arms production28. Rather, bombing had hastened victory chiefly by wrecking Germany’s rail and waterway transport late in the war29. The area offensive, which the BBSU largely wrote off, was British, the transport attacks chiefly American. But the report also underestimated the importance of oil, a second crucial American target set in 1944-5. Skewed though it was, the BBSU also established findings that would serve later generations of historians. It suggested that bombing had cost a modest 7 per cent of the total British war effort, rising to 12 per cent in 1943-4. It stressed the importance for the combined offensive of the arrival of long-range fighter escorts in early 1944 and noted, though with little detail, that the diversion of resources away from battlefronts to the defence of the Reich was a significant result of the offensive30.

Harris, unsurprisingly, took the opposite view, both in his Despatch on War Operations, published only in 1995, and in his memoirs31. While Harris ascribes many achievements to Bomber Command32, the heart of his Bomber Offensive is a robust defence of area bombing. Industrial cities, he wrote, were attacked because that was where Germany’s main industries were; the effectiveness of the offensive was measurable in terms of the tonnage of bombs dropped and the urban area destroyed; if the bombing offensive had not delivered on the promises that he had made for it, it was through lack of resources and the lack of ‘faith in strategic bombing’ of the Allied war leaders. The Americans, Harris suggested, had wasted their time on precision bombing; when they finally saw the benefits of area attacks, in 1945, they defeated Japan without a costly land campaign33.

Bomber Offensive remains more polemical than reliable. Harris’s dismissal of the idea that bombing could have wrecked German morale sat ill with his wartime claims to be able to ‘push Germany over’ from the air34. His claim that the area bombing policy was decided at the highest political level, and implemented by him35, was disingenuous. Harris not only executed the policy but advocated it relentlessly against growing opposition within the Air Staff, until Churchill disowned it in March 1945.

By 1961 the British had not one, but two official histories. Neither was as critical as the BBSU report; neither was as supportive as Harris. The first, the three-volume Royal Air Force 1939-1945 by the novelist Hilary St George Saunders and the historian Denis Richards, appeared in 1953-4 and covered the RAF in both European and Pacific theatres. The assessment of the bombing offensive, though not quite in the Harris mould (it does not claim that bombing could have won the war alone; it concedes the limitations of the area offensive; it considers the death and destruction wreaked on ordinary Germans)36, is nevertheless highly favourable. Richards and Saunders introduce many themes common to later accounts, including the need to do something to attack the German heartland in 1940-42, the early numerical and technological inadequacy of Bomber Command and the remedies that were progressively applied (Gee, and later Oboe and H2S – from 1942), and the contribution to final victory through the diversion of German military resources to the West and to defence rather than attack, the defeat of the Luftwaffe in German skies, and the disabling of the transport network and oil industry37.

The larger official history, by the diplomatic historian Sir Charles Webster and the younger air power historian, Noble Frankland was entirely devoted to the bombing offensive38. The authors successfully insisted, against resistance from the RAF establishment, on full authorial independence as well as access to closed sources.

One of their main innovations was to document the fact that ‘the strategy of the bombing offensive was normally a controversial issue’ – and that it was political39. Thus, for example, they show that the attacks of spring 1942 were as much about securing good publicity that would justify Bomber Command’s existence as about damaging the German war effort40. They detail the decision to bomb Dresden, and Churchill’s disingenuous distancing of himself from the bombing offensive in March 194541. Most strikingly, they set out Harris’s dogged adherence to the area offensive even when enjoined from late 1944, by formal directives and by Chief of the Air Staff Sir Charles Portal, to pursue precision oil and transportation targets42. The account of these exchanges and Harris’s near-resignation led Portal, and the Air Ministry, to seek to censor the official history or even to block publication43.

Focusing chiefly on Bomber Command, the Official History incorporates the USAAF offensive, and the American preference for precision day bombing. In that context, Webster and Frankland identify a turning-point at the spring of 1944, when American air forces won (partial) air superiority over Germany thanks to long-range fighter escorts with disposable extra fuel tanks. Before that, they argued, the Luftwaffe’s command of German skies prevented the Allied air offensive from meeting, or even approaching, its strategic objectives. Bomber Command could penetrate the German defences with losses that were just sustainable, but at night, and at the cost of accuracy. The US Eighth Air Force could in theory achieve selective precision bombing, but could not reach its targets without incurring unacceptable losses. As long as this lasted, ‘it scarcely mattered whether the bombing policy was general [as Harris preferred] or selective [in line with American preferences44].’ And despite spectacular local successes, as at Hamburg, the Allies inflicted no serious damage to the German economy. Only when the long-range fighters achieved air superiority could the offensive proceed with some success45. Thus, wrote Frankland later, ‘If the war had ended in March 1944 for reasons other than a collapse of German civil morale, the Bomber Command offensive would have had to be described as almost a complete failure46.’ Afterwards, by contrast, the offensive contributed ‘a very great deal’ to the German defeat47. Nevertheless, argued Frankland, it could have contributed much more, and perhaps ended the war in 1944, if the effort had not been needlessly dispersed between oil targets, transportation, and Harris’s area offensive.48

Detailed and conceptually sophisticated, the official history remains an indispensable reference. The reviews in 1961, however, largely ignored its subtleties; indeed, the right-wing press berated Frankland (Webster had recently died) for labelling the bomber offensive a ‘costly failure’, which he had not. Later, as Frankland observed in 1993, it was viewed quite differently, as a ‘whitewash of Sir Arthur Harris and Bomber Command’.49 But for the moment, however incorrectly, the Official History was placed with the BBSU report in the broadly sceptical analytical camp and the views ascribed to it permeated other works. Thus for the leading military historian Basil Liddell Hart, writing in his History of the Second World War: ‘The British pursued area-bombing long after they had any reason, or excuse, for such indiscriminate action’ but ‘despite the errors in strategy and disregard for basic morality, the bombing campaign unquestionably played a vital part in the defeat of Hitler’s Germany.’ 50

The sceptical view did not, however, extend to the more ‘popular’ histories that appeared from the 1970s. These covered individual raids and drew substantially on interviews with survivors, chiefly from the RAF but also from the Luftwaffe and the civilian population. Martin Middlebrook’s accounts of the disastrous Nuremberg raid of 30-31 March 1944, and later of the bombing of Hamburg and Berlin, as well as the American raids on Schweinfurt and Regensburg combine meticulous narratives with numerous survivor statements.51 Their conclusions, despite the horrors they depict, show few doubts about the justification for the offensive. But perhaps Middlebrook’s major contribution to the history of the bombing war is his reference work Bomber Command War Diaries, a single-volume guide to all Bomber Command operations of any substance.52

The first general history to integrate witness statements was Max Hastings’s Bomber Command (1979). Within a condensed strategic history of Bomber Command, Hastings includes chapters on four RAF stations at specific moments of the war, on Harris’s underground headquarters at High Wycombe, and, from the German viewpoint, on the firestorm raid on Darmstadt. He also introduces new themes such as the wartime protests against the offensive voiced by such figures as Bishop Bell of Chichester or Richard Stokes MP, and so-called ‘Lack of Moral Fibre’ – the cases of airmen unable to bear the strain of operations. Though drawing on Webster and Frankland, Hastings is much more severe than the official historians. The Americans had made the main contributions by defeating the Luftwaffe, and by wrecking Germany’s oil industry. Area bombing had been a failure, and Harris should have been sacked for sticking to it. The destruction of cities like Darmstadt punished German civilians for their leaders’ crimes but contributed nothing to victory. And thus ‘the cost of the bomber offensive in life, treasure, and moral superiority over the enemy tragically outstripped the results that it achieved.’53 Readable, much-reprinted, and imbued with moral passion, Bomber Command helped entrench sceptical views of the value of the offensive.

Central to the sceptical view was the fact that Germany’s war industries grew fast, despite bombing, well into 1944. By the 1980s, however, this growth was being placed in new contexts. For Richard Overy, whose first book on the subject appeared in 1980, the achievements of bombing should be measured not against actual German production but against what had been planned for a war expected to start in 1942.54 Thus although productivity in the arms industry doubled between 1941 and 1944, bombing ‘placed a ceiling’ on further improvement. It made the supply of components slower and less predictable, obliging firms to hold bigger stocks; it forced the dispersal of industry into smaller, less well-located plants. Thus in January 1945 the German Armaments Ministry estimated that German industry produced ‘35 per cent fewer tanks, 31 per cent fewer aircraft, and 42 per cent fewer lorries’ than it would have done without bombing. All the German officials interviewed by post-war Allied researchers ascribed the economic collapse from January 1945 to bombing.55 For Adam Tooze, indeed, Bomber Command had damaged German production as early as spring 1943, when raids on the Ruhr halted the ‘armaments miracle’ attempted by Hitler’s Armaments Minister Albert Speer; Harris’s error lay in then diverting this effort to a fruitless assault on Berlin.56 Moreover, as Overy points out, a growing proportion of war production went to anti-aircraft defences: 30 per cent of guns, 20 per cent of heavy ammunition, 50 per cent of electro-technical production, a third of production of the optical industry.57 Even the attack on German morale, suggests Overy, was not a complete failure. Absenteeism in the Reich reached 23.5 days in 1944, and rose as high as 25 per cent in some factories such as Ford at Cologne.58 In the areas of worker productivity, the transfers of defences to the Reich, and the diversion of production to anti-aircraft defences, British area bombing might be seen as just as useful as precision bombing. Indeed, Sebastian Cox has argued that it was the dispersal forced in 1942-3, mostly by area bombing, that made German production more dependent on transport links, multiplying the impact of attacks on the German transport system in 1944-45.59

Set against what Mark Connelly called the ‘orthodoxy’ of the post-war surveys and of ‘yet another government statement, the Official History’60 such analyses amounted to a partial rehabilitation. As well as the economic gains, bombing had produced political dividends, sustaining morale at home and offering Stalin a ‘second front’, of sorts, from 1942. These upbeat views were also expounded in the more ‘popular’ histories by Denis Richards or Robin Neillands.61

The rehabilitation itself has not gone unchallenged. In 1991 David Edgerton called strategic bombing ‘a massive misallocation of resources’62 and later queried the detail of the diversion of military effort to Germany’s home defence.63 More remarkable, perhaps, is the renewed note of scepticism in Overy’s substantial recent study.64 The Bombing War: Europe 1939-1945 covers campaigns excluded or marginalised in many earlier accounts: not only the Allied bombing of France and Italy but also Bulgaria, and the German bombing of the Soviet Union. It also examines the ways in which states and societies and the new relationships that developed between peoples and government as a result.65 It concludes that ‘the bombing offensives in the Second World War were all relative failures in their own terms.’66 Although this assessment applies to both German and Allied offensives, Overy is particularly severe towards British area bombing: whether in its origins in inter-war colonial ‘policing’ operations, in the deliberation with which British researchers perfected techniques of burning down whole cities, or in the official lies about what was being attempted, area bombing, for Overy, was morally flawed.67

Bombing and morality

Most works cited hitherto question the morality of the bombing offensive.68 British area bombing is criticised more than American precision bombing, as less effective and more indiscriminate;69 and firestorm raids are understandably seen as the worst. Dresden occupies a distinctive place in this category, for several reasons. The raid destroyed a treasure-house of German baroque architecture; it occurred when the Allied victory was not in doubt (unlike the earlier, deadlier raid on Hamburg); and it triggered the British government’s withdrawal of support for the area offensive, after an unusually frank press briefing prompted Associated Press to state that the Allies had crossed a threshold into ‘terror bombing’.70 The Associated Press despatch caused consternation among the British élite, prompting questions in the House of Commons and ultimately Churchill’s disowning of the bombing campaign a month later.71 Churchill omitted Dresden from his memoirs.72 Harris, by contrast, mounted a predictably vigorous defence: as ‘the largest city in Germany […] which had been left intact’, it was as legitimate a target as anywhere else, and the bombing had been ‘considered a military necessity by much more important people than myself’.73 If nothing else had secured Harris’s status as the stage villain of the area bombing campaign, Dresden would have sufficed.74

After the war, Dresden’s position at the heart of memory was ensured, firstly, by a British pressure group, the Bombing Restriction Committee, which claimed in December 1945 that the raid had killed between 200,000 and 300,000 people, against an already-beaten enemy and a target of no military significance. Of wider impact was David Irving’s 1963 account of the bombing, from a largely German viewpoint. Irving called the raid ‘the biggest single massacre in European history’, put the death toll at 135,000, observed that it failed in its stated purpose of disrupting communications, and enlisted Harris’s own Deputy, Air Marshal Sir Robert Saundby, to write a forward supporting his case.75 Irving’s reputation as a historian has deteriorated since, as he sought to compare the area bombing offensive to the Holocaust, juxtaposing excessive figures for the death toll at Dresden (the best current estimate is 18,000-25,000)76, with gross underestimates of the number of Holocaust victims. But repeated reprints of Irving’s book over more than thirty years ensured its continuing influence, albeit more in Germany than in Britain.77

More respectable historians than Irving have also attacked the morality of the area offensive. Hastings underlines the ‘significant moral distinction between the incidental and deliberate destruction of civilian life in war’, adding that ‘it is hard to look back […] with any pride on such a night’s work as the destruction of Darmstadt.’78 Hew Strachan observes that ‘in the Second World War, [Britain] flouted the norms which underpinned the laws of war’, Overy that the British, American and German air offensives all ‘violated every accepted norm in the conduct of modern warfare.’ If indiscriminate bombing was withdrawn from the charge sheets at Nuremberg, he adds, it was because the Allies’ legal vulnerability on this issue was all too clear.79

The most sustained moral criticism, however, has come from a philosopher, Anthony Grayling. Grayling bases most of his case on just war theory: however just a war may be in itself, the just waging of war requires each act to be necessary and proportionate, and alternative, and less damaging, means towards the intended purpose to have been exhausted.80 If munitions workers are legitimate targets, writes Grayling, no other civilians are, and proportionality requires that non-combatants should not be targeted or exposed to serious risk of becoming casualties.81 That no specific rules against indiscriminate bombing had been ratified by all parties to the Hague Conventions by 1939, that was beside the point; the protection of civilians had been written into umbrella provisions of the Conventions of 1899 and 1907.82

On the specifics of the Allied bombing offensive, Grayling suggests that the fact that the Allied victory was certain by September 1944 detracts from the legitimacy of raids undertaken thereafter.83 And in undertaking area rather than precision bombing, the British were flouting the ethical requirement that alternative means to an intended purpose should be exhausted.84 Area bombing, for Grayling, was ‘very wrong’: neither necessary, nor proportionate, nor consistent with ‘the general moral standards of the kind recognised and agreed in Western civilisation’: Hamburg (and Hiroshima) were no better than the 9/11 attacks on New York. British aircrews were brave men doing something wrong who should therefore have refused to obey orders.85 British governments knew that targeting civilians was wrong; hence their efforts to conceal their actions. And post-war declarations and agreements designed to protect civilians against bombing, especially the 1949 Geneva Convention and its 1977 protocols, constitute ‘a retrospective indictment of the practices they outlaw.’86

Some of Grayling’s specific points are readily countered. The claim that from September 1944 the conflict was nearly ‘over’ ignores the fact that only the Allies’ vigorous prosecution of it secured Germany’s defeat. Grayling also exaggerates the effective precision of precision bombing: several American raids on France, carried out in clear skies against weak air defences, killed over 1,000 French civilians; the record of blind bombing through the cloud cover of the Ruhr was worse.87 But most defenders of the area offensive base their arguments on the exceptionally odious character of the enemy being and the specific predicament of the British in 1940. Thus for Frankland, ‘The great immorality open to us in 1940 and 1941 was to lose the war against Hitler’s Germany. To have abandoned the only weapon of direct attack which we had at our disposal would have been a long step in that direction.’88 Given the technology available, area bombing was ‘Bomber Command’s last and only resort’89 , the only alternative to no bombing at all. The Germans, moreover, had ‘started it’: ‘Cities all over Europe had been attacked by the Luftwaffe and we were merely returning the medicine.’90 ‘Morality’, said a bomber pilot quoted by Overy, ‘is a thing you can indulge in in an environment of peace and security, but you can’t make moral judgements in war, when it’s a question of national survival.’91 And in the context of reverses in North Africa and in the Atlantic in 1941-2 bombing was the only thing resembling a success story that the British could claim.92 For the ace bomber pilot Leonard Cheshire, finally, the bombing offensive was justified by the fact that ‘Every day the war lasted, another ten thousand were exterminated in the concentration camps’ – and thus that it had to be shortened by any means available.93

Many commentators link morality to effectiveness: Stephen Garrett, for example, condemns the area offensive as ‘both a crime and a mistake.’94 Hastings takes a similar view, in more measured terms. But the link is not absolute. Frankland has defended the morality of the offensive while dismissing its effectiveness before March 1944. Overy, by contrast, some of whose assessments of the effects have been more positive, nevertheless joined Grayling in 2012 to debate in favour of a motion that ‘The Allied bombing of German cities in World War II was unjustifiable’, arguing that resources could have been better used to develop fast light bombers capable of precision attacks. The supporters of the offensive, the military historians Patrick Bishop and Antony Beevor, won, with 191 votes against the motion and 115 in favour. This result suggests that no consensus on the subject exists. But the two sides’ views were not wholly opposed: Grayling believed that bombing made a major contribution to the liberation of France, while both Bishop and Beevor condemned the pursuit of area bombing after late 1944.95

Some airmen had doubts about the morality of bombing, both at the time and retrospectively. Pilot Robert Wannop, bombing Saarbrucken, observed himself, ‘a young man with a wife and a beautiful baby daughter, raining death and unbearable horror on similar wives and children. Yet the worst part of it was that I felt no guilt, no sense of repulsion at the enormity of my deed. […] God! What monsters we had become!’96 One of Hastings’s interviewees talked of his nightmares: he had ‘changed his job and started to teach mentally-handicapped children, which he saw as a kind of restitution.’97 But historians have found many more former aircrew aggrieved at their treatment by the government, the public and, especially, the media. Thus one felt ‘disgust and dismay’ at the newspapers’ ‘grovelling and sanctimonious apologia [sic] for the bombing of German cities’ on the fortieth anniversary of VE-Day. Another felt ‘bitter’ that ‘none of the politicians wanted to take responsibility’ for the offensive, allowing the memory of the Bomber Command dead to be ‘tarnished’ A third expressed loyalty to Harris: ‘the fondness for him grew when the criticism of him started. We weren’t just protecting Butch, we were protecting our own reputations.’ Finally, Miles Tripp, who had looked down at Dresden burning and then made sure that his bombs fell in open country, offered a detached, if disabused, view of public opinion: ‘when one’s survival is threatened, one is grateful to those who offer protection. Once the danger is past, one is ashamed that one’s intellectual theories have been so easily overruled by a primitive instinct or emotion, and that the erstwhile helpers are an immediate target for the hostility caused by this sense of shame.’98 The last part of this paper considers how far the wider culture has reflected the historians’ debates and justified the aircrews’ sense of rejection.

‘Black sheep’ or ‘Forgotten Heroes’? Bomber Command in the wider culture

Mark Connelly has called Harris and Bomber Command ‘the black sheep of the British popular memory of the Second World War’, their offensive a ‘missing chapter in the public memory of the Second World War.’ John Nichol and Tony Rennell refer to bomber crews as ‘Forgotten Heroes’.99 Such assessments appear odd, and not only because of the boys’ culture considered earlier: Connelly himself has counted some 570 books on Bomber Command published to the mid-1990s.100 The output has certainly not diminished since; other cultural products have complemented books; and actors in civil society have promoted the memorialisation of the bombing war, culminating in the unveiling of an imposing, even overbearing monument to Bomber Command in 2012.

Positive, mass-audience narratives of Bomber Command have a long pedigree: Paul Brickhill’s The Dam Busters, a biography of the elite 617 squadron, has been in print since publication in 1951.101 The recent material already cited is the tip of a larger iceberg.102 It is heavily based on the statements of bomber crews: able young men with lives to make in the post-war world, and little time to reminisce, but in their later years, far more inclined to tell their stories. Alongside the profusion of general histories, Harris now has a well-researched biography, sympathetic but not hagiographic103, 617 squadron’s 1943 raid on the Ruhr dams has its first new account in 60 years104, and Daniel Swift has written a haunting evocation of bombing bases in the flat landscapes of East Anglia, of literary representations of the bombing war, and of his search for his grandfather’s grave in Holland.105 Many readers of these books, it may be surmised, grew up in the 1960s and 1970s with the Victor and plastic kits.

Film and television have complemented the multiplication of written accounts, despite the obvious difficulties of massing Lancaster bombers for the screen. The film of The Dam Busters, blessed with an instantly memorable theme tune, topped the British box-office in 1955 and was no. 68 in the British Film Institute’s 1999 list of 100 best British films.106 Some cinemas showing The Dam Busters in 1954-5 organised collections for the RAF Benevolent Fund or even opened RAF recruiting offices.107 But The Dam Busters, much in the manner of the Victor, portrayed a single very high-precision raid by the Command’s elite squadron, not the nightly despatch of massed formations to the Ruhr or Berlin. It inspired one imitation in 633 Squadron, a fictional account of a daring raid by a squadron flying twin-engined Mosquitoes, which reflected commonly-experienced realities even less. Pathfinders, a twelve-episode ITV television series of the early 1970s, did better in principle: based on survivors’ accounts, it followed a ‘Pathfinder’ squadron, charged with marking targets as raids started. But neither the scripts nor the acting caught the public imagination as The Dam Busters had. More successful was the BBC’s Harris (1989), which narrated the bomber offensive through a dramatised biography of the Commander-in-Chief. Played by the very popular actor John Thaw, Harris got a sympathetic hearing, but the biopic did not shrink from presenting the offensive’s grim realities.

The fictionalised accounts have been matched by documentaries. Thames Television’s 1973-4 series The World at War devoted the twelfth of its 26 episodes to strategic bombing and featured original footage and interviews with British, American and German aircrew, with German civilian survivors, and with senior strategists on all sides including Harris and Speer. But Episode 12 ends at April 1944, a point at which the offensive appeared as largely unsuccessful. As the only coverage in subsequent episodes was of Dresden, the overall balance of The World at War was decidedly negative. However, later documentaries, including Channel 4’s Reaping the Whirlwind (1997), have been much more upbeat. Some recent productions have used well-known actors as presenters, and attempted to re-create aspects of operations, emphasising their difficulty. Thus the veteran television actor Martin Shaw, in Dambusters Declassified (2010), ‘retraces’ 617 Squadron’s dams raid journey; the documentary also includes an interview with the former mistress of the operation’s leader, Wing Commander Guy Gibson. In Bomber Boys (2012), the film star Ewan McGregor enlists his brother, an RAF pilot, to learn to fly a Lancaster: a brief history of Bomber Command is interwoven with Colin McGregor’s training sessions. While German survivors of the Hamburg raids are interviewed for the programme, the climax, inevitably, is when the McGregors finally take to the air with the blessing of survivors of 617 squadron. Commercially successful, the formula inevitably runs the risk of trivialising its subject. Altogether more thoughtful, and more sensitive to the moral dilemmas of the crews, is Steven Hatton’s Into the Wind (2012); but it was shown to the smaller audiences of the Yesterday channel.

If there was some substance in the 1970s to portrayals of bomber crews as ‘forgotten heroes’ or ‘black sheep’, such claims had little justification by the early twenty-first century. It is tempting to draw a comparison with the memories of German victims. As survivors of Germany’s wartime generation neared the end of their natural lives, works such as Jörg Friedrich’s The Fire (2003) claimed that the bombing offensive had been a ‘taboo’ subject in Germany – although, as Dietmar Süss has shown, the ‘taboo’, at least at local and regional level, is largely imaginary.108

The memory of the bombing war is also heavily sustained by a variety of actors within civil society. One is the RAF itself, whose public visibility has greatly increased since the 1982 Falklands War. Here, for the first time since the largely unreported late colonial conflicts of the 1950s and 1960s, the RAF was in action in what proved to be a highly popular war. Its combat role has continued through two wars with Iraq, the Kosovo conflict of 1999, the long Afghan war, the 2012 air strikes on Libya, and, from December 2015, over Syria. Within the UK, the visibility has been reinforced by the opening of two museums, at Hendon in London and Cosford in Shropshire. The Hendon museum, opened in 1973, unveiled a Bomber Command hall ten years later. The Battle of Britain Memorial Flight, stationed at 617 squadron’s former base at Coningsby in Lincolnshire, operates not only the Spitfires and Hurricanes of World War 2, but also the UK’s one Lancaster still in flying order (although the first Lancaster only flew sixteen months after the Battle of Britain ended).109 At the same time the RAF Historical Branch has developed its sponsorship of conferences and publications (of the BBSU survey, but also of Harris’s Despatch, and of a range of air power books).110 The memorialisation undertaken by the RAF itself is complemented by that of the Imperial War Museum, whose director from 1960 to 1982 was Noble Frankland. The main museum’s library houses collections of photographs, former aircrew diaries, and papers of senior RAF officers. In 1976, moreover, the IWM opened an air annexe at the former RAF station at Duxford in Cambridgeshire, with a collection of historic aircraft and regular air displays.111 Bomber Command itself has held its own reunions since 1949, and in 1985 a Bomber Command Association was formed to ‘educate and inform the general public in the work and history of Bomber Command’. It claimed 6,000 members at the start of the new millennium.112

Churches have memorialised the bombing, in highly contrasting ways that show ‘how the memory of the Second World War could be fragmented and regionalized.’113 Across East Anglia, Bomber Command aircrew who served in nearby stations are celebrated in stained glass windows, usually dating from the 1950s. Bombers stand next to angels in Ely and Lincoln cathedrals; in the church at Great Yarmouth (which suffered several German raids) a window bears the Bomber Command motto – ‘Strike hard, strike sure.’ More widely known, however, because more international, is Coventry, which represents the German Blitz on Britain almost as much as Dresden stands for the Allied offensive against Germany. The two cities are twinned, and on 13 February 2000, the first Dresden anniversary of the new millennium, the bishop of Coventry, preaching in Dresden’s Kreuzkirche, said that ‘Hitler’s war had unleashed a whirlwind into which we were all swept. The dynamic of war swept away our inhibitions. When the British and American air forces destroyed Dresden, we had suppressed our moral principles.’114 Starting from Coventry in 1945, three nails from the roof of the wrecked St Michael’s Cathedral, bent together to form a cross, became the symbol of the cathedral’s renewal; its replication across other destroyed churches in Europe became the symbol of a broad commitment to reconciliation, reaffirmed when the new cathedral was consecrated in 1962. The Community of the Cross of Nails, based in the new St Michael’s cathedral, has partner churches in 27 countries, including 63 in Germany. 115 Following German unification, the Dresden Trust was founded in Britain in 1993 with the initial purpose of helping to rebuild the Dresden Frauenkirche, which had been left in ruins under the GDR, and the broader one, again, of promoting and perpetuating reconciliation.116

Bomber Command also, finally, has visible, public memorials. A statue of Harris was unveiled (amidst vocal protests) by the Queen Mother outside St Clement Danes, the central church of the RAF in the Strand, London, on 31 May 1992, the fiftieth anniversary of the thousand-bomber raid on Cologne. Altogether more ambitious was the Bomber Command memorial in Green Park, opened by the Queen on 28 June 2012. Despite their royal patronage, both monuments were financed by public subscription, amounting to £8 million for the Green Park memorial, not government money.117 The campaign to build the monument, led by the Bomber Command Association, attracted backing from many sources: Robin Gibb, leading member of the 60s and 70s pop group the Bee Gees; popular historians such as Kevin Wilson and Patrick Bishop, both critics of the government’s failure to promote a memorial, which they ascribed to concerns about Anglo-German relations118 ; the right-wing, Eurosceptic press (the Daily Telegraph and above all the Daily Express and the Daily Mail); and right-wing political donors such as Lord Ashcroft, former Deputy Chairman of the Conservative Party, who contributed £1 million.119 Few wartime causes have been so politically marked.

The overblown Green Park edifice is not alone. By the coastal path at Beachy Head, another, almost ostentatiously modest monument, one metre wide by two metres long, marks the spot where many bomber crews flying south got their last sight of Britain. And at Lincoln, close to the headquarters of Bomber Command’s no. 5 group, a 31-metre spire and a series of walls of remembrance unveiled in October 2015 form the heart of what is intended to be an International Bomber Command Centre. By 2015, then, too late for many airmen, the upsurge in memorialisation had ensured that Britain has not one Bomber Command memorial, but three.

By way of conclusion

The bombing war has remained the most contentious aspect of Britain’s World War 2 record, but not because it was ‘forgotten’, an expression better reserved for much of the war in the Far East. It has been contentious above all because of the gulf between the exceptional courage of the young men who served in Bomber Command and the horror that they inflicted on the German civilian population. To celebrate the bravery of the aircrew is to belittle the suffering of the civilians who died; to state clearly that the bombing offensive violated the laws and norms by which civilised human beings wage war diminishes the courage of the aircrew. The extraordinary difficulty of straddling this gulf explains the unease even of some of the aircrew themselves. The difficulties are compounded, as Süss observes, if the international context is taken into account. Germans seeking to promote a sense of national victimhood have seized on the Official History and the more sceptical British accounts. And the efforts at reconciliation coming from British churches run the risk of establishing a moral equivalence between the two belligerents.120

At the war’s conclusion, to the shock of aircrews and their commander-in-chief, governments abruptly withdrew the vigorous support they had lent to Bomber Command’s offensive over five years. At the same time both the British and American post-war bombing surveys, and the later British official history, concluded that bombing had not been nearly as effective as its proponents had suggested, while the message of reconciliation articulated from Coventry, in a country where the Church’s position as a leader of opinion was still strong, entailed an ethical rejection of the bombing offensive. This, in the 1960s and 1970s, was the nearest that the United Kingdom came to a consensus opposed to the bombing campaign. The consensus was never universal, however; it did not prevent the publication of the Richards and Saunders history of the RAF, or the enormous popularity of the Dam Busters, both book and film, among all ages, and the war comics and plastic kits among children. By the 1990s, the history was being rewritten and the achievements of the offensive revised upwards. This did not create a new ethical consensus, even between historians, but it did suggest that Bomber Command had made a significant contribution to winning the war. Both that and the wider visibility of both the armed forces in general and the RAF in particular made it easier to celebrate the achievements of Bomber Command. Praise for the aircrew then rolled out across a wide range of literary and other cultural production, with the efforts of the Bomber Command association finding a ready reception in the broader civil society. The culmination of this process was the triumphant memorialisation of Bomber Command at Green Park. The danger is that the Bomber Command memorial has both mobilised and reinforced right-wing Eurosceptical forces in civil society – in particular the right-wing press – and that the memories of Bomber Command have been captured by a chauvinistic and inward-looking project. For those aircrew members who joined Bomber Command in order to secure, not only an Allied victory, but a Europe reconciled and at peace with itself, this would be a betrayal.

The Bomber Command window, Lincoln Cathedral

http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3654680

Detail of the Bomber Command window, Ely Cathedral

http://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-ely-cathedral-bomber-command-window-24157865.html

Detail of the Bomber Command window, Great Yarmouth church

http://en.tracesofwar.com/article/45963/Memorial-Window-RAF-Bomber-Command.htm

The Queen opens the Bomber Command memorial, Green Park, June 2012

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-18600871

The monument at the Lincoln International Bomber Command Centre

http://www.lincolnshireecho.co.uk/pictures/GALLERY-International-Bomber-Command-Memorial/pictures-27910307-detail/pictures.html

The unveiling of the Bomber Command memorial at Beachy Head, April 2013

http://www.theargus.co.uk/news/10387319.Bomber_Command_tribute_is_unveiled_at_Beachy_Head/

The statue of Sir Arthur Harris in front of St Clement Dane’s Church, London

http://www.visualphotos.com/image/1x10546675/london-england-uk-statue-of-sir-arthur-bomber-harris-1992-by-st-clement-danes-church-the-strand

Bomber crews’ graffiti preserved on a ceiling at the Eagle pub, Cambridge

http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3420989

One of several versions of the Lancaster bomber available as an Airfix kit

http://www.airfix.com/uk-en/the-dambusters-avro-lancaster-b-iii-special-operation-chastise-gift-set-1-72.html

- 1. John Ramsden, ‘Myths and Realities of the “People’s War”, in Britain’, in Jörg Echternkamp and Stefan Martens (eds.), Experience and Memory: the Second World War in Europe (Oxford: Berghahn, 2010), pp. 40-52.

- 2. John Foot, Italy’s Divided Memory (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2009).

- 3. Henry Rousso, The Vichy Syndrome. History and Memory in France since 1944, tr. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, Ma. and London: Harvard University Press, 1991); see also Olivier Wieviorka, Divided Memory: French Recollections of World War II from the Liberation to the Present, tr. George Holoch (Stanford, Ca: Stanford University Press, 2012);

- 4. Angus Calder, The Myth of the Blitz (London: Jonathan Cape, 1991).

- 5. Martin Middlebrook and Chris Everitt, The Bomber Command War Diaries, 1939–1945 (Leicester: Midland Publishing, 2000 (1st edn. London, Viking, 1985)), p. 708, 711.

- 6. Figures from United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Volume 2A: Statistical Appendix to Over-All Report (European War), Chart 1, http://www.wwiiarchives.net/servlet/action/document/page/113/12/0 (accessed 16 November 2015). The total of 2,770,540 US tons converts to 2,513,770 metric.

- 7. Dietmar Süss, Death from the Skies: How the British and Germans Survived Bombing in World War II (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 6.

- 8. Claudia Baldoli and Andrew Knapp, Forgotten Blitzes: France and Germany under Allied Air Attack (London: Continuum, 2012), p. 3, 261-2.

- 9. Cf. Middlebrook and Everitt, Bomber Command War Diaries, p. 413-4, 440, 580-1, 669, 682; Max Hastings, Bomber Command (London: Michael Joseph, 1979), p. 325; Sönke Neitzel, ‘The City Under Attack’, in Paul Addison and Jeremy A. Crang (eds.), Firestorm: the Bombing of Dresden, 1945 (London: Pimlico, 2006), p. 66-77; p. 75.

- 10. The National Archives of the United Kingdom, Kew (henceforth TNA): AIR2/7852; Harris to Under-Secretary of State, Air Ministry, 25 October 1943. Extracts from this exchange may be found in Tami Davis Biddle, Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare: The Evolution of British and American Ideas about Strategic Bombing, 1914–1945 (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2002), pp. 219-221.

- 11. For a fuller discussion of press and radio coverage in the war, cf. Andrew Knapp, ‘The Allied Bombing Offensive in the British Media, 1942–45’, in Andrew Knapp and Hilary Footitt (eds.), Liberal Democracies at War: Conflict and Representation (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), pp. 39-65.

- 12. The National Archives of the United Kingdom, Kew (TNA) AIR 2/7852, Harris to Under-Secretary of State, Air Ministry, 23 December 1943.

- 13. Noble Frankland, ‘Some Thoughts about and Experience of Official Military History’, Journal of the Royal Air Force Historical Society, 17, 1997, 20.

- 14. Hastings, Bomber Command, p. 343-4; Henry Probert, Bomber Harris. His Life and Times (London, Greenhill Books, 2001), p. 344-5, 361-2. Harris was, however, promoted to the rank of Marshal of the Royal Air Force, the highest in the RAF.

- 15. Sebastian Cox, (ed.), British Bombing Survey Unit, The Strategic Air War Against Germany, 1939-1945. The Official Report of the British Bombing Survey Unit (London: Frank Cass, 1998), p.166.

- 16. Noble Frankland, History at War. The Campaigns of an Historian (London: Gilles de la Mare, 1998), p. 106-113.

- 17. Cf. Probert, Bomber Harris, p. 417.

- 18. Patrick Bishop, Bomber Boys. Fighting Back, 1940-1945 (London: HarperPress, 2007), p. 366-389.

- 19. Adam Riches, with Tim Parker and Robert Frankland, When the Comics Went to War. Comic Book War Heroes (Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 2009), p.10; The Independent 11 November 2011.

- 20. Riches, When the Comics, p. 10, 128, 154, 220.

- 21. The Victor, 59, 7 April 1962; 1309, 22 March 1986.

- 22. Michael , Warrior Nation. Images of War in British Popular Culture, 1850-2000 (London: Reaktion Books, 2000), p. 234-5.

- 23. Mark Connelly, We Can Take It! Britain and the Memory of the Second World War (Harlow: Pearson Longman, 2004), p. 240; , Warrior Nation, p. 235-6.

- 24. The Independent, 11 November 2011: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/news/50-years-of-war-adaptable-commando-comic-still-going-strong-2335027.html, accessed 19 November 2015.

- 25. Morris Heggie (ed.), The Best of the Victor. 50th Anniversary Edition (London: Prion, 2010). Andy McNab, Intorduction, p.4.

- 26. http://www.airfix.com/uk-en/catalogsearch/result/?q=lancaster, accessed 19 November 2015.

- 27. Sebastian Cox, ‘The Overall Report in Retrospect’, in BBSU, The Strategic Air War, p. xxxix.

- 28. BBSU, The Strategic Air War, p. 79.

- 29. Cox, ‘The Overall Report in Retrospect’, p. xxiii.

- 30. BBSU, The Strategic Air War, p. 69.

- 31. Sir Arthur Harris, Bomber Offensive, (London: Greenhill Books, 1990: 1st edn. London: Collins 1947)).

- 32. Ibid., p. 265-7.

- 33. Ibid., p. 259-264.

- 34. Ibid., p. 78; Hastings, Bomber Command, p. 259.,

- 35. Harris, Bomber Offensive, p.89.

- 36. Denis Richards and Hilary St George Saunders, The Royal Air Force 1939–45, vol. III, The Fight is Won, (London: HMSO, 1975 (1st edn. 1954)), pp. 10, 270.

- 37. Ibid., pp. 381-391.

- 38. Sir Charles Webster and Noble Frankland, The Strategic Air Offensive Against Germany, 1939–1945, 4 vols. (London: HMSO, 1961).

- 39. Webster and Frankland, Strategic Air Offensive, vol. III, p. 290. My italics.

- 40. Ibid., p. 298.

- 41. Ibid., p.103, 117.

- 42. Ibid., p. 306.

- 43. Frankland, History at War, p. 108-9.

- 44. Webster and Frankland, Strategic Air Offensive, vol. III, p. 294.

- 45. Webster and Frankland, Strategic Air Offensive, vol. III, p. 40, 291-4.

- 46. Frankland, History at War, p. 67.

- 47. Noble Frankland, ‘Overview of the Campaign’, in Royal Air Force Historical Society, Reaping the Whirlwind. Bracknell Paper no. 4. A Symposium on the Strategic Bomber Offensive, 1939-45, 1993, pp. 3-8: p. 5: http://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/documents/Research/RAF-Historical-Society-Journals/Bracknell-No-4-The-Bomber-Offensive.pdf, accessed 20 November 2015

- 48. Frankland, History at War, p. 70.

- 49. Frankland, ‘Overview of the Campaign’, p.8.

- 50. Basil Liddell Hart, History of the Second World War (London: Cassell, 1970), p. 612.

- 51. Martin Middlebrook, The Nuremberg Raid, 30-31 March 1944 (London: Penguin, 1986 (1st edn. 1973)0; The Battle of Hamburg. The Firestorm Raid (London: Cassell, 2000 (1st edn. Allen Lane, 1980)); The Schweinfurt-Regensburg Mission: American Raids on 17 August 1943 (London: Cassell, 2000 (1st edn. Allen Lane, 1983)) The Berlin Raids. The Bomber Command Winter, 1943-44 (London: Cassell, 2000 (1st edn. Allen Lane, 1988).

- 52. Cf. Middlebrook and Everitt, Bomber Command War Diaries.

- 53. Hastings, Bomber Command, p. 350-2.

- 54. Richard Overy, The Air War 1939-1945 (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2005 (1st edn. London: Europa, 1980)); Richard Overy, War and Economy in the Third Reich (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

- 55. Overy, War and Economy, p.373-4.

- 56. Adam Tooze, The Wages of Destruction. The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy (London: Penguin, 2007 (1st edn. Allen Lane, 2007), p. 598-601.

- 57. Overy, The Air War, p. 122.

- 58. Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won (London: Pimlico, 1996 (1st edn. Jonathan Cape, 1995)), p. 133; Richard Overy, Bomber Command 1939-1945 (London: HarperCollins, 1997), p. 197.

- 59. Cox, ‘The Overall Report in Retrospect’, p. xxx.

- 60. Mark Connelly, Reaching for the Stars. A New History of Bomber Command in World War II (London: I.B. Tauris, 2001).

- 61. Denis Richards, RAF Bomber Command in the Second World War: the Hardest Victory (London: Penguin, 2001 (1st edn New York: W.W. Norton, 1995)), p. 220; Robin Neillands, The Bomber War. Arthur Harris and the Allied Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 (London: John Murray, 2001), p. 292.

- 62. David Edgerton, England and the Aeroplane. Militarisation, Modernity and Machines (London: Penguin, 2013 (1st edn. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1991)), p. 130.

- 63. David Edgerton, Britain’s War Machine. Weapons, Resources and Experts in the Second World War (London: Penguin 2012 (1st edn Allen Lane, 2011)), p. 283-290.

- 64. Richard Overy, The Bombing War. Europe 1939-1945 (London: Allen Lane, 2013).

- 65. On this theme, see also Claudia Baldoli, Andrew Knapp, and Richard Overy (eds.), Bombing, States and Peoples in Western Europe, 1940-1945 (London: Continuum, 2011).

- 66. Overy, The Bombing War, p. 609.

- 67. Ibid., p. 48, 328-337, 629.

- 68. The immediate post-war surveys do not, being concerned entirely with effectiveness; the official history does so (Webster and Frankland, Strategic Air Offensive, vol. III, p.114), but obliquely, in its discussion of the political impact of the bombing of Dresden.

- 69. Interestingly, the French perception was quite different. The French found that while Americans bombed indiscriminately, the British took adequate measures to minimize French civilian casualties. This reflects a partial truth. The Americans’ belief in their capacity to effect precision bombing meant that they bombed France in much the same way as they bombed Germany, though with fewer incendiaries; the British, on the other hand, realizing that they could not inflict area bombing on French cities as they did on German ones, altered their techniques and usually flew somewhat lower over French targets. However, when the British marked their targets badly, or undertook really big attacks (as, for example, over Le Havre in September 1944), the results could be just as devastating as those achieved by the Americans, or more so.

- 70. Cf. Tami Davis Biddle, ‘Wartime Reactions’, in Paul Addison and Jeremy A. Crang (eds.), Firestorm: the Bombing of Dresden, 1945 (London: Pimlico, 2006), p.96-122: p. 105-6.

- 71. Cecil King, With Malice Towards None: a War Diary (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1970), p. 290; Webster and Frankland, Strategic Air Offensive, vol. III, pp. 112-3.

- 72. Richard Overy, ‘The Post-War Debate’, in Paul Addison and Jeremy A. Crang (eds.), Firestorm: the Bombing of Dresden, 1945 (London: Pimlico, 2006), p.123-142: p. 124, 127-8.

- 73. Harris, Bomber Offensive, p. 242.

- 74. Cf., in Paul Addison and Jeremy A. Crang (eds.), Firestorm: the Bombing of Dresden, 1945 (London: Pimlico, 2006): Hew Strachan, ‘Strategic Bombing and the Question of Civilian Casualties up to 1945’, p.1-17: p. 16; Tami Davis Biddle, ‘Wartime Reactions’, p.122; Donald Bloxham, ‘Dresden as a War Crime’, p. 180-208: p. 181, 208; Dietmar Suss, ‘The Air War, the Public, and Cycles of Memory’, in Jörg Echternkamp and Stefan Martens (eds.), Experience and Memory: the Second World War in Europe (Oxford: Berghahn, 2010), pp. 180-196; p. 185.

- 75. David Irving, The Destruction of Dresden (London: William Kimber, 1963), p. 5, 7, 158, 178, 234.

- 76. Dietmar Süss, Death from the Skies: How the British and Germans Survived Bombing in World War II (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 521.

- 77. Overy, ‘The Post-War Debate’, p. 139-140. Overy points out, for example, that the Swedish arms-control specialist Hanx Blix used Irving’s figure of 135,000 in preparing the 1977 protocols to the Geneva Convention.

- 78. Hastings, Bomber Command, p. 351.

- 79. Strachan, ‘Strategic Bombing’, p.2; Overy, The Bombing War, p. 630.

- 80. A.C. Grayling, Among the Dead Cities (London: Bloomsbury, 2006), p.210-4.

- 81. Ibid., p. 228, 250, 258.

- 82. On this point, and particularly the so-called ‘Martens Proviso’, cf. also Overy, The Bombing War, p. 801-2; Geoffrey Best, Humanity in Warfare: the Modern History of the International Law of Armed Conflicts (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980), p. 262-8; Horst Boog, ‘Harris – a German View’, in Harris, Despatch on War Operations, p. xxxvii-xlv; and Antonio Cassese, ‘The Martens Clause: Half a Loaf or Simply Pie in the Sky?’, European Journal of International Law, Vol. 11 No. 1 (2000), p. 187–216: http://www.ejil.org/pdfs/11/1/511.pdf accessed 24 November 2015.

- 83. Ibid., p. 69, 264

- 84. Ibid., p. 267.

- 85. Ibid., p.276-9.

- 86. Ibid., p.141, 229.

- 87. Cf. Biddle, Rhetoric and Reality, p. 228-9. The raids on Nantes on 16 September 1943 and on St-Étienne on 26 May 1944 each killed over 1,000 civilians; that on Marseille on 27 May 1944 killed over 1,800.

- 88. Noble Frankland, quoted in Bishop, Bomber Boys, p. 382.

- 89. Webster and Frankland, Strategic Air Offensive, vol. I, p. 180.

- 90. Air Vice-Marshal Jack Furner, in RAF Historical Society, Reaping the Whirlwind. Bracknell Paper no. 4. A Symposium on the Strategic Bomber Offensive, 1939-45, 1993, p.63.

- 91. Charles Patterson, quoted in Overy, Bomber Command 1939-1945, p. 201.

- 92. Sir John Curtiss, in RAF Historical Society, Reaping the Whirlwind, p.63.

- 93. Interview with Leonard Cheshire, quoted in RAF Historical Society, Reaping the Whirlwind, p. 85.

- 94. Stephen Garrett, Ethics and Airpower in World War II: The British Bombing of German Cities (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1997), p.198.

- 95. Intelligence2, ‘The Allied bombing of German cities in World War II was unjustifiable’, debate held at the Royal Institute of British Architects, London, 25 October 2012, on http://www.intelligencesquared.com/events/bomber-command/, accessed 23 November 2012.

- 96. John Nichol and Tony Rennell, Tail-End Charlies. The Last Battles of the Bomber War, 1944-45 (London: Penguin, 2004), p.200.

- 97. Hastings, Bomber Command, p. 352.

- 98. Nichol and Rennell, Tail-End Charlies, p. 405-9.

- 99. Connelly, Reaching for the Stars, p. 157; Connelly, We Can Take It!, p. 256; Nichol and Rennell, Tail-End Charlies, p. 405.

- 100. Connelly, Reaching for the Stars, p. 147.

- 101. Paul Brickhill, The Dam Busters (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 1983 (1st edn. Evans Brothers, 1951)).

- 102. Among many other works, the iceberg includes, in roughly chronological order: Mel Rolfe (ed.), Hell on Earth. Dramatic First-Hand Experiences of Bomber Command at War (London: Grub Street, 1999); Kevin Wilson’s trilogy, Bomber Boys, Men of Air, and Journey’s End (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, and Cassell, 2005-2011); Rupert Matthews, RAF Bomber Command at War (London: Hale Books, 2009); Roy Irons, The Relentless Offensive: War and Bomber Command 1939-1945 (Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2009).

- 103. Cf. Probert, Bomber Harris.

- 104. James Holland, Dam Busters. The Raid to Smash the Dams 1943 (London: Corgi, 2013 (1st edn. Bantam Press, 2012).

- 105. Daniel Swift, Bomber County. The Lost Airmen of World War Two (London: Penguin, 2011 (1st edn. London: Hamish Hamilton, 2010).

- 106. See http://www.cinemarealm.com/best-of-cinema/top-100-british-films/, accessed 24 November 2015.

- 107. , Warrior Nation, p. 226; Süss, Death from the Skies, p. 466-7.

- 108. Jörg Friedrich, The Fire. The Bombing of Germany, 1940-1945 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006 (1st edn. Munich, 2002)); Süss, Death from the Skies, p. 518-9.

- 109. http://www.raf.mod.uk/bbmf/, accessed 24 November 2015.

- 110. http://www.raf.mod.uk/ahb/, accessed 24 November 2015.

- 111. http://www.iwm.org.uk/visits/iwm-duxford, accessed 24 November 2015.

- 112. Süss, Death from the Skies, p. 461; http://www.rafbombercommand.com/master_the_association.html, accessed 24 November 2015.

- 113. Süss, Death from the Skies, p. 467-8.

- 114. Quoted in Alan Russell, ‘Why Dresden Matters’, in Paul Addison and Jeremy A. Crang (eds.), Firestorm: the Bombing of Dresden, 1945 (London: Pimlico, 2006), 161-179: p. 164.

- 115. http://www.coventrycathedral.org.uk/ccn/our-partners/, accessed 25 November 2015.

- 116. Russell, ‘Why Dresden Matters’, p.168-172.

- 117. https://www.rafbf.org/bomber-command-memorial/upkeep-club, accessed 24 November 2015.

- 118. Kevin Wilson, Journey’s End. Bomber Command’s Battle from Arnhem to Dresden and Beyond (London: Phoenix, 2011 (1st edn. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2010)), p. 405; Bishop, Bomber Boys (‘About the Author’, p. 6).

- 119. Daily Mail, 24 March 2015.

- 120. Süss, Death from the Skies, pp. 472, 495.