Learning aids, used in schools, are the starting point in Sophie Leclercq’s search for part of colonialism’s visual history; for it is through things seen and touched daily that the student learned to think and feel. From the depths of various museums’ collections, she has extricated posters, gold stars, blotting papers, games, alphabets, and cut outs in order to grasp their meaning. Her work brings to life a world of exotic and false images of a colonial empire hitherto unknown to children.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Images

from the colonies as objects

Sophie Leclercq

With the advent of the Third Republic schools in France became an institution, where both the intangible, knowledge, as well as the political, were instilled. This institutionalization was reliant on a place, the school, and objects, the learning aid, being materialized. Now, as before, learning aids refer to a pedagogical support in a designed and didactic form. In an even more tangible way for the student, educational material refers to the totality of the daily objects used in learning. The fact that ‘school manual’ can also be used for ‘school textbook’ illustrates how learning is embodied: knowledge can be held manually, in the palm of the hand.

The collections of the national museum for education (Munaé) are the basis on which this research is built; it is the successor to the pedagogical museum created in 1879 at the initiative of Jules Ferry, then minister for public education. The father of a secular public school for all was also a keen proponent of colonial expansion and, as such, schools became an echo chamber for the Empire. The colonial empire was turned by the educational world into a favored object of representation, following various types and on a large scale of mediums, be they for direct use within the school or for extracurricular activities: posters, rewards, notebook covers, blotting papers, games, alphabets, cutting boards, maps, etc. Though many of these are not things, we would tend to qualify them as ‘objects’. What position, then, does the Empire play in schoolchildren’s visual environment? What are these representations and how are they shaped by their materiality? What kind of ‘agency was sought?1A. Gell, L’Art et ses agents, une théorie anthropologique, Dijon, Les Presses du réel, 2009.

We might answer these questions by considering the images in questions as ‘objects’, by questioning the relationship between iconography and device, as well as the exchanges they might have had with images of the Empire, brought together as they were within the space of the school.

What school imagery says of the Empire

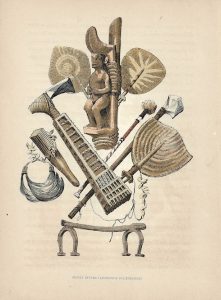

Fig. 1. Cahiers d’enseignement illustrés n°79 : Colonies françaises, ‘Objets divers (archipels polynésiens’, c. 1900, ed. by Baschet. Munaé, Paris. © Munaé (musée national de l’Éducation) / Photographies reproduites avec l’aimable autorisation du Munaé.

School imagery of the colonies filled a triple need: documentary, aesthetic and politic. It was about making the colonies known and making them loved.

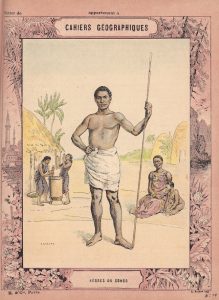

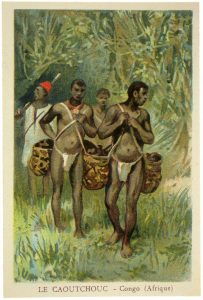

In the first place images of the colonies called upon scientific data, for example cartography, ubiquitous in schools.2On colonial maps, see H. Blais, Mirages de la carte. L’invention de l’Algérie coloniale, Paris, Fayard, 2014. Schoolchildren were asked to draw freehand maps of the colonies in order to assimilate the Empire, to know its every corner, to make it their own. Ethnology was also part of this scientific data mobilized to increase knowledge of the Empire. For example, sets of photographs taken during ethnographic missions were afterwards replicated on glass slides, meant to be projected. Museum objects were also shown as specimens of indigenous culture, sometimes even as sets, just like the scenography in contemporary museums (fig. 1). On other mediums, like for example the covers of notebooks or the small rewards printed as thematical sets for the schoolchildren, local people were pictured according to ethnographical norms (fig. 4).

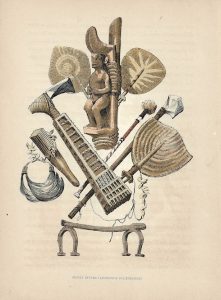

Fig. 2.1 et 2.2 Pierre Portelette, La France d’outre-mer, ‘L’existence à Tahiti’» and ‘Récolte de la canne à sucre’, 1938, 39 x 104 cm, ed. Delagrave. Munaé, Paris.© Munaé (musée national de l’Éducation) / Photographies reproduites avec l’aimable autorisation du Munaé.

This colonial imagery catered to esthetic requirements. At school, just as elsewhere, exotism was prized, making the colonial world highly desirable and seductive.3On the works produced by schoolchildren, see J. Bondaz (dir.), Le Magasin des petits explorateurs, Arles/Paris, Actes Sud/musée du quai Branly, 2018. In order to do so, so called colonial art was often used as inspiration.4S. Leclercq, ‘Éduquer et séduire. Les arts coloniaux dans les images scolaires (1871-1958)’, in D. Jarrassé (dir.), Les Arts coloniaux. Circulation d’artistes et d’artefacts, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, Éditions Esthétiques du Divers, 2021, pp. 41-52. Many orientalist and colonial paintings were reproduced for classrooms, like for example the monumental work by Horace Vernet, Capture of the Smala of Abd el-Kader (1844). The pervasive power of the arts could be less direct and yet just as potent when it came to the aestheticization of the colonies. For example, visions of Tahiti would often derive from an idealized and stereotypical image of the island paradise (fig. 2), a testimony to how artistic output, most notably that of Paul Gauguin, had been internalized, integrating the “edenic code” theorized by Roland Barthes5R. Barthes, ‘Par où commencer ?’, Poétique n°1, 1970, p. 3.

Lastly, at the crossroads of these documentary and esthetic ambitions, school imagery was inherently born out of political ambition, in the context of strengthening the Republic. By increasing the knowledge, and the love of, the colonies, imperial policy was enhanced and new generations could be convinced of the merit of colonialism as a source of national glory. To that end, a multifaceted iconography was used, sometimes heroic, featuring the architects of the Empire, other times allegorical, in representations of colonial life, French flag floating at their center, where the colonial act was always glorious: that is to say, images of domination or of the ‘colonial peace’ that resulted from it.

Beyond the mere illustration, here to give a visual form to textual content, these images were made to be reproduced on school artefacts, toeing the line between graphic material and object.

Visiting the Empire

The schoolroom could be transformed into a display space, to enable learning and to invite the student’s reverie and escapism. In many cases, printed sheets representing naturalistic colonial produce or maps of the Empire were enhanced with landscapes and typologies of the various tribes, suggesting a tri-dimensional view of these far-away territories. Teachers also had at their disposal photographic prints that they would sometimes organize on larger boards that represented the colonies. The class wall then became a space for visual layouts, at the disposal of the teacher.

Large scale mural posters were edited in the context of sets dealing with the colonies. For example, the six sheets on ‘overseas France’, of 1938, by Pierre Portelette, recreated an image of the colonial world as utopia made real, and where colonial order prevailed (fig. 2). Each sheet is a meter long, big enough to be immersive, but also of a size that allowed them to be used in schools and put up all together. This set makes each area its own, while still providing a panoramic view (just like the format) of the Empire. Indeed, once the sheets were hung one next to another, they formed a single continuous fresco. In this way it is almost like a miniature colonial exhibition, where the student’s gaze could travel from his desk to the colonies within the restricted space of the classroom.

The colony within reach

Another aspect of school imagery is that of the collection, that is to say the accumulation and safekeeping by the student of images, often because they were offered as rewards. One finds a large amount of prize books and rewards. In that vein the album Madagascar, once again illustrated by Pierre Portelette (1931), is set up in an Italian format, with 21 colored sheets. As specified on the cover, ‘the images in this album were taken from indigenous drawings’. It becomes therefore about supplying an object that comes directly from the colonial world, under a guise close to that of the sketchbook.

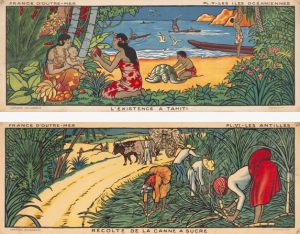

Fig. 3. Blotting paper with an advertisement for ‘Petit Negro ’ », c. 1955. Munaé, Paris. © Munaé (musée national de l’Éducation) / Photographies reproduites avec l’aimable autorisation du Munaé

The students would also manipulate blotting papers on a daily basis: they were frequently full of advertisements in the twentieth century. Advertisement latched upon colonial imagery in an often unflattering, even racist, manner, and thusly entered schools. A character could be used in multiples ways, not only in a publicity on blotting paper, but also as quasi-educational merchandise. This is what happened with the underwear brand Petit Negro, who, besides the blotting papers, would show the adventures of its titular character in filmstrips thanks to the ‘Office scolaire d’étude par le film’.6State organism for the projection of films and images in schools, founded in the 1930s In this way, a caricatural yet very immersive and seductive narrative device was offered to the students.

Another printed object that made the most of imperial imagery is the cover of notebooks. Printed in thematical series, and blending text and image, the covers could be detached and kept by the student. The illustrations on the covers would often be set within an ornamental frame, sometimes with the addition of a plaque, just as one might find on museum works (fig. 4). This pictorial device transformed the cover of the notebook into a small painting, once more encouraging the student to keep it with the others and thusly forming his own personal gallery.

Fig. 4. ‘Nègres du Congo’, from Cahiers géographiques, n°19, ill. by Gilbert et Fraipont, c. 1900, Hachette et Cie éd. Munaé, Paris © Munaé (musée national de l’Éducation) / Photographies reproduites avec l’aimable autorisation du Munaé n° inv. 1979.06985.91).

This idea of the collection was also at the heart of images being gifted as rewards. They would become for the student objects of affect, both through its easily handled shape as a small book, and through its purpose as a reward. Once again, these reward-images would take the shape of printed series dedicated to the Empire or would integrate the colonies on a wider scale: local produce (fig. 5), people, tribes, habitats, events linked to colonial conquest, etc. The illustrated side of the card would often be completed by a small explanatory text on its reverse, written as one might a museum label.

Fig. 5. ‘Le caoutchouc – Congo (Afrique)’, 1905. Munaé, Paris (© Munaé © Munaé (musée national de l’Éducation) / Photographies reproduites avec l’aimable autorisation du Munaé, n° inv. 1997-3257 (4).

The Empire as a playground

Finally, games were objects linked to informal and domestic education and they could also be found in schools. It is mainly through lotteries that the Empire was ‘brought into play’: lotteries of the departments, geographical or even the five regions of the world; they all acted as ornamental and playful visual offerings for a colonial space that was part of ‘larger France’. The Lottery of the colonies and protectorates of France, printed around 1890, was in a box representing the famous men who had built the Empire (fig. 6). Inside it, each card held the name of a colony, and each number that of a colonial product. Therefore, its playful manipulation would familiarize the student with colonial resources, which he could make his own while playing.

Fig. 6. ‘Loto des colonies et protectorats français’, c. 1890, éd. J.L. Munaé, Paris (© Munaé (musée national de l’Éducation) / photographies reproduites avec l’aimable autorisation du Munaé)

Amongst educational archives, we also find images the student could transform into objects, like, for example, the cardboard sheets made by Pélican Blanc in 1936. Each of the colonies is represented by a supposedly typical character. Through cutting and bending, the student could then make little cardboard figures, able to stand thanks to a small base, and arranging them into a pocket-sized diorama of the French colonies

These three functions that were exhibition, collection and play allow us to understand how educational imagery was presented. It followed various systems of materiality, all involving spatialization, collective contemplation and the handling of images, within a set of images meant to invoke pleasure and desire, but also the colonial world they represented. The image was no longer just an educational illustration meant to teach something, it also became an object-image, both recreating the colonies on a microcosmic scale, capable of being appropriated and handled by schoolchildren in the intimacy of the schoolroom, and desirable by its very materiality.

Thus, the school environment allowed for a discovery of the colonies through various visuals means. They all, however, held to the central tenet of increasing knowledge and love of the Empire, as well as successfully spreading republican propaganda in its favor. The images are affected by their medium, sometimes even made into objects by it: educational objects, but also colonial objects. This, in turn, brought the Empire ‘into’ the classroom, made its presence felt, although the former was far away and so different from this communal space. One could posit that the colonial world in itself became objectified by its display in schools, and, consequently allowed the youth of France to appropriate it, in a narrative that was that of the national epic, the colonial epic.

[1] A. Gell, L’Art et ses agents, une théorie anthropologique, Dijon, Les Presses du réel, 2009. [2] On colonial maps, see H. Blais, Mirages de la carte. L’invention de l’Algérie coloniale, Paris, Fayard, 2014. [3] On the works produced by schoolchildren, see J. Bondaz (dir.), Le Magasin des petits explorateurs, Arles/Paris, Actes Sud/musée du quai Branly, 2018. [4] S. Leclercq, ‘Éduquer et séduire. Les arts coloniaux dans les images scolaires (1871-1958)’, in D. Jarrassé (dir.), Les Arts coloniaux. Circulation d’artistes et d’artefacts, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, Éditions Esthétiques du Divers, 2021, pp. 41-52. [5] R. Barthes, ‘Par où commencer ?’, Poétique n°1, 1970, p. 3. [6] State organism for the projection of films and images in schools, founded in the 1930s

Bibliography

Barthes, R., ‘Par où commencer ?’, Poétique n°1, 1970, p. 3.

Blais, H., Mirages de la carte. L’invention de l’Algérie coloniale, Paris, Fayard, 2014.

Bondaz, J., (dir.), Le Magasin des petits explorateurs, Arles/Paris, Actes Sud/musée du quai Branly, 2018.

Gell, A., L’Art et ses agents, une théorie anthropologique, Dijon, Les Presses du réel, 2009.

Leclercq, S., ‘Éduquer et séduire. Les arts coloniaux dans les images scolaires (1871-1958)’, in D. Jarrassé (dir.), Les Arts coloniaux. Circulation d’artistes et d’artefacts, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, Éditions Esthétiques du Divers, 2021, pp. 41-52.

Renonciat, A., (dir.), Voir/Savoir. La pédagogie par l’image au temps de l’imprimé, Futuroscope, Scérén-CNDP, 2011.

Sophie Leclercq holds a PhD in cultural history. She has worked in both the research and education department of the musée du quai Branly (both before and after its opening) and at the CNDP/Réseau Canopé (Ministry for Education). She now works and teaches at Sciences Po, and published in 2010 La Rançon du colonialisme, les surréalistes face aux mythes de la France coloniale (les presses du réel), issued from her doctoral research.