Our knowledge of Russia and the USSR is no longer in focus. That is the conclusion delivered here by three researchers who offer us a historiographical overview of painting, film, architecture, and urban planning. In their company, we exit a history centered around the decryption of ideological messages effectively imposed by the state apparatus. It is henceforth a question of artistic practices, commissions, markets, sales and resales, distribution, ways of exhibiting works, audiences, and artworks that avoid the model of propagandistic rhetoric out of a concern, in particular, for economic profitability. This economic question thus weighs heavily on everything, including fields in which this dimension had been left out under the pretext that capitalism had officially been banished.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

The Role of the Economy in Soviet Pictorial Art During the 1920s and 1930s

Cécile Pichon-Bonin

Since the fall of the Communist Bloc, many historians of the USSR have attempted, through a meticulous study of archival sources, to go beyond the antagonistic approaches of “totalitarianism”[ref]This school of thought, which predominated until the end of the 1960s, was the heir to the works of Hannah Arendt and Raymond Aron on totalitarianism. It postulated a monolithic political regime, an all-powerful State exercising absolute control over an indoctrinated and lawless society where terror reigned. This school focused on political history in the strict sense, wherein the State coincided with the Party, and history was the history of the leaders of this Party, mainly of its omniscient and omnipotent head. The advocates of this approach thus had a tendency to take the ambitions of the regime for reality and to disregard the tensions and conflicts that nevertheless really existed. We count among the representatives of this school Leonard Shapiro, Robert Conquest, Martin Malia, and Mikhail Heller.[/ref] and “revisionism.”[ref]In the 1970s, a current of social history emerged that was immediately accused of “revisionism” by the totalitarian school. This current said the opposite of what was being said in prior research on the subject by proposing a history “from below” and not “from above.” These historians were disposed to depoliticize discourse on the USSR, to deideologize it, to inquire into the relations a society entertained with its institutions, to break with the demiurgic conception of the Party, to stop privileging political power as the main analytical source, and instead to look into the economic and social spheres. The “revisionist” movement naturally owes much to the Annales School. Major events no longer appear as the result of a political initiative coming from Stalin but as the product of domestic tensions. Two main criticisms have been directed against this current: on the one hand, it is said to have made hasty generalizations; on the other, it is said to have a tendency to minimize terror and violence as significant, nay major, components of the regime. Among the notable partisans of this school are Stephen Cohen, Moshe Lewin, Sheila Fitzpatrick, and Gabor T. Rittersporn.[/ref] In the field of the history of the arts, this attempt has been expressed quite recently in research into issues surrounding patronage, commissions, and exhibitions.[ref]We are thinking here in particular of the works of Christina Kiaer and her students at Columbia University and then at Northwestern University, the exhibitions organized by Ekaterina Degot, and the research work of Galina Yankovskaya.[/ref] Our work is part of that movement, which introduces some material and economic considerations into the study of 1920s and 1930s Soviet painting. We propose to nuance here the totalitarian idea that the economy constituted merely a lever used to apply an ideology.

A consecutive presentation of the situation in the 1920s–which was marked by the artistic diversity of groups–and then of the period of the Cultural Revolution (1928-1932)–which was characterized by the installation of the Stalinist form of organization–will allow us to highlight changes in the position of the artist with regard to such varied questions as: With what economic realities were artists forced to compromise? How did those realities relate to ideological considerations? What was their relation to the very form of works? What sorts of coercive and free spaces were thereby created?

The Economic Importance of Artistic Groups in the 1920s

Within the framework of the New Economic Plan (NEP), artists could once again join forces within associations. Such connections were made on the basis of networks of friends and artistic sensibilities, and they generally led to the drafting of various programs. For an artist, joining a group answered an economic need, as well: groups obtained State subsidies, which were useful in organizing exhibitions, buying materials, or lending money to one of their members in case a specific problem arose.

The structures of these groups proved to be more or less complex, depending upon the collective. The Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR)[ref]This group, founded in 1922, counted among its noteworthy members, the former Wanderers. They also held a view of art that was inherited from the Russian Realists of the late nineteenth century.[/ref], for example, possessed its own publishing organ and had an office that served as an intermediary for artists and buyers.

These groups also held varying views about State economic intervention in artistic activities. Thus, the AKhRR proposed to develop the system of commissions that was especially active during the Civil War, when the Red Army was demanding propaganda works. The Society of Easel Artists (OST) and other groups, on the contrary, wanted the State to invest more in the purchase of works and to increase the allocation of subsidies.

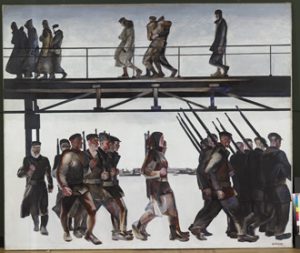

Fig. 1. Alexandre Deïneka,The Defense of Petrograd, 1964, copy of the 1927 painting, oil on canvas, 210 x 238 cm, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

In the Twenties, private clients remained scarce. Purchases of artworks were divided up among several commissions that had comparable amounts of funding.[ref]Vitalii Manin, Iskusstvo v rezervatsiy (Moscow: Editorial URSS, 1999), p. 120.[/ref] Each commission belonged to a specific State administration or a museum and competed with the other ones.[ref]Thus, the Revolutionary Military Council (Revvoensovet) or the Soviet Narodnykh Komissarov (SNK, Soviet Council of People’s Commissars) had their own commissions. At the same time, the main museums, such as the State Tretyakov Gallery or the Museum of the Revolution, vied with the State Commission officially charged with the purchase of artworks. This last commission, as well as the museums, were connected to two different departments of the Glavnauka, the Chief Administration for Science and Scholarship.[/ref] A system reminiscent of the art market was thus restored, in large part within the State apparatus itself.

Among those commissions, the so-called State Commission declared that it would privilege the acquisition of contemporary Soviet paintings, sculptures, and drawings in order to support the easel arts, which were then in the throes of crisis[ref]The budget allocated for purchasing works kept on growing during the second half of the Twenties and ended up overtaking the total amount of grants given to artist groups in 1927-1928. See, on this topic, the Katalog priobreteniy gosudarstvennoy komissiy po priobreteniyam proizvedeniy rabotnikov izobrazitelnykh Iskusstv [Exhibition catalogue of works purchased by the Commission for the Acquisition of Works by Visual Arts Workers] (Moscow:Sovetskiy khudozhnik, 1929).[/ref]. Emphasis on the fact that the easel arts were undergoing a major crisis serves to encourage a revision of the traditional interpretation of the multidisciplinary character of artists. Grasped as the sign of the creative freedom that was shaking things up in the 1920s, this multidisciplinary character of artists at the time, while it did indeed constitute a specific, theorized attitude and artistic approach, must also to be read within a particular economic context. The artist had to broaden his repertoire of practices in order to intervene, successively or simultaneously, in a variety of fields and to diversify his possible sources of income.

The highly intense activity of some artists during the Thirties in the fields of graphic arts and theater design therefore cannot be thought of solely in terms of taking refuge from or creating a rupture with prior artistic practice. Artists’ work was based on multiple forms of expertise, which could sometimes allow them to adapt to the context.

In this materially difficult set of circumstances, painters welcomed the vast series of commissions artists were granted by the People’s Commissariat for Public Instruction (which was headed by Anatoliy Lunacharskiy) for the organization of an exhibition to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution. This event is generally thought of as the first Soviet State commission, and, as in the United States, this interventionist policy was perceived by those concerned as a sign of State support for creative artists. The event celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Red Army, which was organized by the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, did not, however, arouse the same level of enthusiasm among the AKhRR’s rivals. Indeed, the Association took advantage of the occasion to continue its maneuvers of intimidation and to destabilize other groups by deciding to invite some of their members. The confrontations these exhibitions occasioned inaugurated the Stalinist era and the period of the Cultural Revolution.

The Cultural Revolution and the Establishment of Anniversary Commissions

These two exhibitions show that the term commission thus designates a multifaceted reality. In the case of the event celebrating the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution, receipt of sketches and of completed works was subject to discussion between the artist and Lunacharskiy in person. In his memoirs, Sergei Luchishkin related his experience:

Fig. 2. Sergueï Loutchichkine, Famine in the Volga Region, 1927

“In order to respond to a commission offer for the anniversary show, I had chosen a complex subject, that of famine in the Volga region during the Civil War. I wanted to express the deep sufferings the people of this region had been able to outlive. . . .

“According to the contract, the procedure for authorizing initial sketches was simple. A. V. Lunacharskiy personally decided whether they would be rejected or accepted. I therefore went to him with my preliminary work. Having looked at my work, which was truly gloomy, he said, ‘The works of yours with which I am familiar are so gay, so anchored in our new life, and suddenly you choose a theme that doesn’t suit you at all! The famine in the Volga region was a horrifying trial, and we are celebrating a great holiday; why cast a pall over it with such memories? I ask you to put this theme aside and paint something that corresponds to who you are. Little time remains; bring me a simple sketch done in pencil and I’ll trust you.’

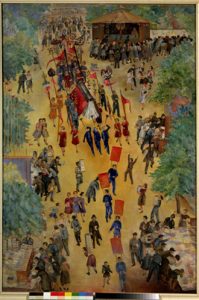

Fig. 3. Sergei Luchishkin, Book Festival, Tverskoy Boulevard, 1927, oil on canvas, 159.7 x 111 cm, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

“I had an idea right away. That Spring, on Tverskoy Boulevard, a large book market was being held. Publishers and book dealers set up commercial stalls along the street. You could meet some writers, and parades had been organized. There was a lot of merry commotion. In a few days, I returned to see Anatoliy Vasilyevich with my pencil sketch and he signed it.”[ref]Sergei Luchishkin, Ya ochen lyublyu zhizn (Stranitsy vospominanya) (Moscow: Sovetskiy khudozhnik, 1988), p. 116.[/ref]

At the same time, in order to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the founding of the Red Army, the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia worked with the Revvoensovet on implementing the contracts for artistic commissions. The theme of the work was defined in advance and the payment of the money followed along with the different stages of execution: two presentations of sketches, then the submission of the completed work. In order to handle their subject, the artists could go on creative field assignments. As early as the 1920s, the AKhRR had undertaken to organize artists’ trips on the model of those taken by the Wanderers, but while directing creative artists toward industrial sites, kolkhozes, and Red Army training facilities.

The ambition of such visits was to furnish artists with the visual material needed for the treatment of their subject and to strengthen their knowledge and understanding of Soviet reality. According to the members of the AKhRR, direct contact with the motif would allow artists to develop their political and Soviet consciousness. The contract therefore included some obligations, mainly of a thematic nature, the members of the Association privileging, in practice, the choice of Soviet subjects.

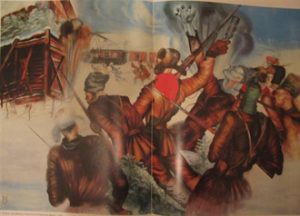

Fig. 4. Yuri Pimenov, The Seizing of an English Blockhaus, 1927, oil on canvas.

The artists of the AKhRR also promoted a mimetic form of art that would be legible and understandable. Despite the fact that within this group and in this exhibition an approach to art that was based on the great principles of late nineteenth-century Russian Realism predominated, some major works were nevertheless created within the framework of these contracts. We are thinking in particular of Alexander Deineka’s The Defense of Petrograd and Yuri Pimenov’s The Seizing of an English Blockhouse, a picture with explicit expressionist references.

The term commission thus designates a variety of practices (and the procedure was to become even more varied in 1932, at the time of the two exhibitions commemorating the fifteenth anniversaries of, respectively, the Russian Republic and the Red Army).[ref]Pressed by time, the organizers sometimes commissioned pictures that had already been begun, paying out money to aid in the completion of certain works.[/ref] During the Cultural Revolution, the Party, through its violently activist youth members (mainly members of the RAPKh, the Russian Association of Proletarian Artists, beginning in 1931), tried continually to impose a stricter form of organization on commissions in order to orient the choice of subjects toward a “Soviet thematics” and artistic expression toward a legible and comprehensible form. Inspired by the practices of the AKhRR, the young activists were going to try, in particular, to use the creative field assignments toward those ends, employing such assignments as a tool for “reeducating fellow travelers.” But the ambient disorder generated by the great institutional reforms, changes in personnel,[ref]On the issue of the elimination of old personnel by the younger generation on which Stalin was going to lean for support, see Sheila Fitzpatrick, Cultural Revolution in Russia, 1928-1931 (Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 1978).[/ref] and resistance from artists themselves were not going to allow the RAPKh to achieve its ends. Moreover, one should not neglect the impact of economic factors here and in the organization of the artistic life.

Between Ideological Constraints and Economic Facts

To artists, the anniversary commissions appeared as a way to allow them to work and to make themselves known. All creative workers sought to obtain as many such commissions as possible within this framework. Nevertheless, in 1932 a shortage of paint and canvas that followed the order to limit imports and to develop national production was to curb the work of young artists, in particular, to a considerable degree. Some were not even able to honor the terms of their commissions.[ref]See, on this topic, the polemic that broke out in the press and the complaints of artists concerning the availability of materials. Among the most significant articles we can cite are: Yur, “God Raboty ‘Khudozhnika,’” Byulleten Vsekokhudozhnika, April 1931: 10-17; Tyutyunnik, “zhivopisnyy material,” Byulleten Vsekokhudozhnika, June 1932: 50 ; L. Bachinskiy, “O khudozhestvennykh kraskakh,” Sovetskoe iskusstvo, September 15, 1932 ; D. P. Sterenberg, “Udacha èntuzyastov,” Sovetskoe iskusstvo, September 15, 1932.[/ref]

At the same time, these major commissions, which were offered only for anniversaries of the Revolution and the Red Army–that is, around once every five years–could not constitute artists’ sole source of income. Other systems existed in parallel,[ref]For a description of the various systems of granting commissions, we refer to our article “Peindre en URSS dans les années 1920-1930. Commandes, engagements sous contrat et missions de créations,” Cahiers du monde russe, 49:1 (January-March 2008): 47-74.[/ref] like contract hires, which the All-Russian Cooperative of Artists (Vsekokhudozhnik) played a major role in developing.

This socio-professional organization, created in 1928, quickly became a major base of material life for artists. It intervened on such topics as commissions, creative field assignments, the distribution of subsidies (for pregnant women, for example), and the organization of exhibitions. (Indeed, the Cooperative had at its disposal an exhibition site, which was rather rare at the time.) Starting in 1931, the Cooperative thus organized its much-talked-about bazar-show, the goal of which was to sell the exhibited works. It thus played at the time the role of a gallery taking a percentage on acquisitions.

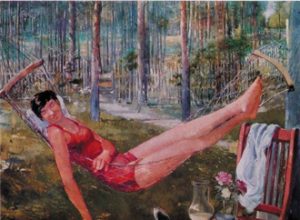

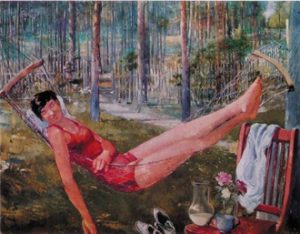

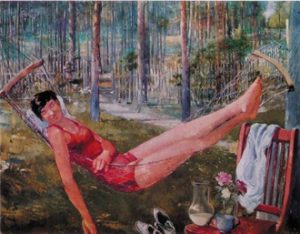

Fig. 5. Yuri Pimenov, Young Woman in Hammock, 1934, oil on canvas, 129×161 cm, Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg.

In order to build up its funds, the Cooperative also set up, like the State publishing house and the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, a system of contract hires. This system involved paying a painter a monthly salary for the delivery of a certain number of works over the period of a year. Until the second half of the Thirties, monitoring of the artist seems to have been relatively light on the Cooperative’s end, in particular as regards thematic requirements. In 1935, Yuri Pimenov, for example, in responding to the theme Assessments of the First Five-Year Plan, Storming the Second Five-Year Plan!, painted Young Woman in a Hammock.In her writings, Christina Kiaer has reexamined the traditional opposition between the Western art market, thought of as the expression of democratic freedom, and the system of Soviet commissions, understood as a manifestation of the operation of a totalitarian machine.[ref]Christina Kiaer, “Was Socialist Realism Forced Labor? The Case of Alexander Deineka in the 1930s,” Oxford Art Journal, 28:3 (2005): 321-45.[/ref] This historian proposes that we consider contract hires as an alternative to the Western art market. More generally speaking, the interweaving of various systems (creative field assignments, commissions, sales of works) seems to us more apt to offer this alternative–especially in 1934-1935, when the new Stalinist nomenklatura, seeking respectability, constituted a new private clientele base in demand of works.

Taking economic factors into account when studying the Soviet painting of the 1920s and 1930s allows us to shed additional light on this patch of art history. That approach also invites us to examine from another perspective such facts as the formation of artistic groups or the multidisciplinary character of artists’ practices during the Twenties, and it encourages us to offer new explanatory factors that may add to previous studies. At the same time, the introduction of economics allows us to propose a more precise definition for the organization of the varied systems of commissions and sales-purchases of works. We come to understand, then, that certain economic facts curtailed the application of a highly strict ideological line, as is shown by the activity of the All-Russian Cooperative of Artists, which worked in particular with a private clientele. Conversely, a constraint like the shortage of canvas and paints could aggravate the material situation of some artists, without pressures of an ideological nature being at the origin. The link between economics, ideology, and artistic practice thus restores to the Soviet system its real complexity.

Bibliography

Bown, Matthew Cullerne. Art under Stalin. Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1991.

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. Cultural Revolution in Russia, 1928-1931. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Jankovskaja, Galina. Iskusstvo, Dengi i politika: khudozhnik v gody pozdnego stalinizma. Perm: Permski Gosudarstvennyy Universitet, 2007.

Kiaer, Christina. “Was Socialist Realism Forced Labor? The Case of Alexander Deineka in the 1930s.” Oxford Art Journal, 28:3 (2005): 321-45.

Manin, Vitalii. Iskusstvo v rezervatsiy. Moscow: Editorial URSS, 1999.

Cécile Pichon-Bonin has a Ph.D. in art history and is conducting postdoctoral research at the Centre d’études des mondes russe, caucasien et centre-européen (CERCEC, the Center for the study of the Russian, Caucasian, and Central European worlds). She defended her dissertation on Painting and Politics in the USSR During the Interwar Period: The Path of Members of the Society of Easel Artists (OST). Pichon-Bonin has also published several articles and delivered various lectures on 1920s and 1930s Soviet painting. She integrates into her approach issues relating to institutional history and to the social history of art, while taking a particular interest in the operation of systems for offering commissions and organizing exhibitions. She has also studied channels of circulation and the content of the discourse of Soviet critics. Her new research project is devoted to children’s book illustrations in the USSR during the 1920s and 1930s. She runs a tutorial on method as part of Laurence Bertrand Dorléac’s art history course at Sciences Po, where she also teaches a course on the analysis of images.