“Race wars are perhaps going to start up again. Within a century, we shall see several million men kill one another other in one fell swoop. The entire East against the entirety of Europe, the Old World against the New! Why not? In another form, great collective projects like the Isthmus of Suez are perhaps rough drafts, preparations for conflicts whose monstrosity we cannot even conceive.”

In his Correspondance, Gustave Flaubert could not avoid the mind-numbing fears of his time, a period that was avid for exoticism as well as keen for political passions caught up in the decline of the West. We now have thinkers, writers, and artists who have unconsciously fashioned the rods by which they are to be punished and, just as much, to punish themselves for a terribly awkward legacy. Obviously, the debate will not end anytime soon about the new Quai Branly Museum or in any other museum. For, we now know that every such site involves an ordering of the world in the name of the worship of art. The sole exception today seems to be those temples of culture where people still do not want to raise the problem of how one’s explicit and implicit world views are expressed in actual fact.

Tzvetan Todorov has told us better than anyone else how crushing and oppressive the history of the discourse on the other has been. “In all times,” he writes, “men have believed that they were better than their neighbors; the only things that have changed are the vices and defects imputed to them.” In his preface, Todorov paid tribute to Edward Saïd’s seminal book on Orientalism because he felt the need to recount, finally, the interlocking fates of power and knowledge.

We now know that Napoleon read the Orientalists before occupying Egypt. Indeed, “one of the most tangible results of this invasion was an immense amount of philological and descriptive work.” Trouble will always come from the discourse on the others. For, he who is the master on the level of speech will be, quite simply, the master of everything. Whether one speaks well or ill of the other, the very act of designating him is a sort of violence.

Through their respective studies, books, and exhibition catalogues, Rémi Labrusse and Benoît de l’Estoile have the merit that comes not only from the richness of their scholarship but also from the newness of their thinking. Both invite us to pose in another way the question of the connections between taste, knowledge, and power. Each one reminds us, after his own fashion, in what way, aesthetic or scientific, knowledge–knowledge of any kind, anywhere and whenever, yesterday, today, or tomorrow–can be organized, instrumentalized, and debased.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of October 11 2007

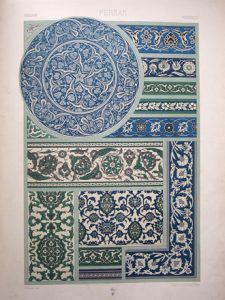

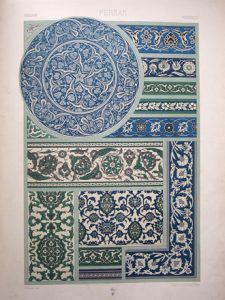

Surface tile with letter fragment, rosette, and saz leaf, Turkey, “Iznik,” c. 1575, engobed ceramic, glazed painted decoration, height: approx. 20cm; length: approx. 24 cm, Paris, Museum of Decorative Arts (holdings of the Department of the Arts of Islam of the Louvre Museum), purchased from Alexis Sorlin-Dorigny, February 14, 1890.

1. “Arts of Islam”: Today, this expression has taken on a legitimacy that critics who contest its claim to cover the products of cultural areas extending from Andalusia to Indonesia and from Central Asia to Mali challenge only at the margin. The distinction between Islam and islam allows one to insist upon surmounting the religious standpoint as a way of designating artefacts whose aesthetic unity had gradually been identified during the course of the second half of the nineteenth century through the Western gaze and as a function of the West’s own needs. The expression “Mohammedan” Art, despite criticisms of its overly religious connotations (which would later make it give way to the term “Islamic” Art, while the content remained almost identical), was aimed above all at foregrounding its purely aesthetic aspects, but it later came to substitute itself for generic characterizations, such as “Oriental” Art, historicist ones, like that of “Saracen” Art (with its medieval connotations), or, especially, ethnoracial ones, like those of “Arab” Art, “Moorish” Art, “Persian” Art, and so on.

2. Purely aesthetic? Certainly less so than its principal zealous advocates had dreamt. Such an outlook was able to flourish in Europe, during the final decades of the nineteenth century, first of all on account of an unprecedented disintegration of “Moslem” societies, from Morocco to India, which were staggering beneath the blows dealt by the colonial or paracolonial expansion of the Western industrial powers. From this standpoint, taste for the arts of Islam constitutes one of the many strata of a discourse whose political mainsprings Edward Said analyzed under the generic term of Orientalism. The extraordinary influx of artefacts from those other shores, which drew their aura in part from their status as fragments, greatly facilitated the development of “purely” aesthetic interpretations about the language of “Mohammedan” ornamentation. Such interpretations were controlled by Western connoisseurs who, most often, did not worry about linking their views in a deep way to any linguistic or historical forms of knowledge.

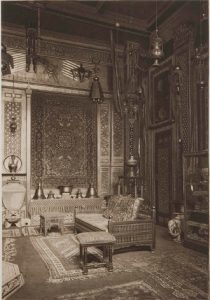

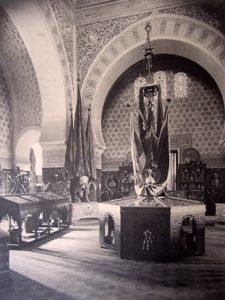

The “oriental” salon of Albert Goupil, 9 rue Chaptal in Paris, prior to 1888 (Catalogue des objets d’art de l’Orient et de l’Occident, tableaux, dessins composant la collection de feu M. Albert Goupil [Paris: Drouot, Mes Escribe et Paul Chevalier], Charles Mannheim exhibition at the Imprimerie de l’art, April 23-27, 1888).

A majority of these connoisseurs shared the prevailing convictions of their time–notably, the idea that, as a whole, the cultures of Islam belonged to the past, preferably a medieval one, and that the present-day weakness of those cultures doomed them to accelerated decadence and, eventually, annihilation. As for the connection between aesthetics and political-economic power, it was ever apparent, whether it was a matter of providing Western factories with models for designing products suitable for export to the “Orient,” of stimulating native industries when the countries in question had been transformed into colonies, or, more generally, of entering into the “mind” of these societies, the better to control them in the competition with other colonial powers.

3. It is nonetheless inappropriate to deduce from this that taste for the arts of Islam did not have any meaning of its own. The network of private connoisseurs who promoted such a taste readily prided themselves on its uniqueness in relation to the various manifestations of Orientalism. Not only were they hardly concerned at all with “Orientalist” science, but above all, on the aesthetic level, the task they set for themselves was to restore to this kind of art its truth, as against the insipid, misguided ways of those whom Viollet-le-Duc, in 1874, called the “partisans of fantasy in everything.”

It was a matter of “shattering the[ir] dear idol” by revealing the male rationality behind Islam’s decorative language as against its supposedly enchanting feminine display, underscoring thereby its abstract rigor rather than its unbridled sensuality.

Main hall of the Exhibition of Mohammedan Art in the new Algiers madrasa (M. Petit architect), April 1905.

Institutionally, this movement was taken over by decorative arts museums–young institutions that, flourishing in the 1860s in the wake of the South Kensington Museum of London, had to find an identity of their own in relation to fine arts museums and ethnographic museums. Oriental arts in general and the arts of Islam in particular constituted one of the most effective vehicles for such identity construction: it was within the walls of decorative arts museums, first and foremost, that this field was constituted and that, beyond their documentary status, these artefacts conquered an artistic autonomy which could then be offered to Western designers as a model.

4. If there was indeed one aspect through which this movement was able to distinguish itself from the discourse of Orientalism, it was the near-obsessive desire that Islam be reinstituted as an active subject, a master of rational formalist rigor, the very one who, in contrast to the Far East, seemed to have taught the West the marvels of expansive ornamental form as early as the medieval period. And even more than that, for, quite often, the formal features, approached with solemnity, ended up nurturing reflections of a moral-aesthetic character about how those features were to be articulated in tandem with social life. For these three reasons–confinement of Islam within a generic reference to the Orient, sensitivity to connections between art and civilization, and, finally and above all, establishment of Islamic form as a subject in its own right, one to be imitated and not treated as an object to be controlled–one can talk about an Islamophilia based on emotional intuition more than on scientific knowledge and yet distinct from the reveries of Orientalism. Islamophilia demonstrated an active passion for the promotion of a decorative message that, though totally transformed by our desires and totally held within the grip of our needs, was associated, by a network of connoisseurs, theoreticians, and practitioners of the decorative arts, with the vast hope for an “Oriental” renaissance of their own society.

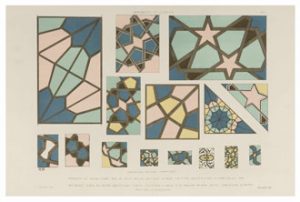

Albert Racinet, “Persan. Faïences émaillées et vernissées. La famille bleue, verte et blanche” [sic, for a set of Ottoman ceramics], in L’Ornement polychrome. Deuxième série. Cent vingt planches en couleur, or et argent. Art ancien et asiatique, Moyen-Âge, Renaissance, XVIIe, XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. Recueil historique et pratique avec des notices explicatives (Paris: Firmin-Didot, no date [1885-1888]), plate 29.

5. Still, it must be noted that the intention of this impulse with utopian overtones was to go beyond historically-based–or, a fortiori, ethnoracial–forms of cultural particularism in favor of a kind of universalism whose primary impact was an eclipse of religious interpretations. These Islamophiles–at least those in France, who were organized in circles gravitating around the Central Union of Decorative Arts and its museum–often were marked by secular, republican leanings, on the faith of which they promoted a lay reading of Islamic ornamentation, itself deemed admirable to the extent that it could be detached from its native culture. Whence the relatively weak impact of racialist clichés, which were certainly repeated on every possible occasion, but rarely in order to establish interpretive mechanisms. As for the historical dimension, it was championed above all as a way of counterbalancing the touching precariousness of artefacts that were worn down by use and that, in addition, were destined to disappear at an accelerated rate owing to modernization. This situation but sharpened the contradiction between a desire for history and, this desire notwithstanding, a rejection thereof with regard to a corpus whose grandeur was, in the eyes of its defenders, based on the ahistorical character of its formal grammar. Only this ultimate disenchantment would have allowed the aesthetic lesson of Islam to liberate the West in turn from the dizzying burden of memory and to bring it back to life in the present by dispelling the specter of those imitations in which, it was thought, nineteenth-century eclecticism had enduringly become lost.

6. At bottom, Islamophile taste and the collections reflecting that taste, which were designed to act on the Western decorative consciousness and to sway it, were indeed linked to a specter. We are speaking here not only of the specter of a West condemned to mere copying, unable to live freely in the present, and held down by the increasing weight of various and, what’s more, innumerable pasts, but also, at a more basic level, of the specter of a degeneration of our Being-in-the-world, one measured paradoxically by the yardstick of our power to destroy other cultures. On all sides–that is to say, beyond the circle of the “antimoderns,” to borrow an expression whose dualism is in this instance inoperative–what people worried about was the increasing “ugliness” being spread by the West like leprosy beyond its own shores, itself a symptom of a “degrad[ation of] our moral intellect,” as Richard Redgrave wrote in London in 1876. What seemed to be fermenting within this mass of technoindustrial products was a tendency to forget the basic task of artistic work: transforming a finite material practice into an infinite life-experience.

Adalbert de Beaumont and Eugène Collinot, “Combinaison de lignes géométriques à l’aide desquelles il est facile d’obtenir des dessins complets, se modifiant à l’infini, en variant les couleurs,” in Encyclopédie des arts décoratifs de l’Orient. Ornements de la Perse (Paris, 1880), plate 1.

7. In other words, the appropriative drive of the modern West, which was particularly evident and violent with regard to the arts of Islam, stemmed from a divided collective consciousness, both sides of which were nourished by feelings of superiority and inferiority, power and collapse, melancholy and revolutionary activism, acceptance of the colonial situation and cultural-political self-criticism. The contradiction grew between the global power of the West, spreading out over the world, and a sense of weakness, which can be likened to what Rémi Brague has called European “secondariness”: cultural identity based on the endless quest for origins both prior and external to itself and condemned thereby to constant self-questioning. Indeed, never was this contradiction sharper than in the late nineteenth century. One is entitled to think that this structural inferiority, this dizzying sense of weakness lodged at the heart of a superpower, fed one and the same movement. That movement occurred under the impact of an accentuation of tensions, acts of depredation of unprecedented breadth, produced by a sort of melancholic hubris and a critical disquietude (of equally unprecedented intensity) with regard to this spreading destruction. And that destruction involved the dismantlement of entire societies and the pulverization of aesthetic and cultural systems within the curio cabinets of museums and collectors. Within this conflict, a panic-induced desire took shape that let itself transformed by a decorative message drawing its instaurating aura from the perception of its otherness; at the same time, another desire was born, a desire to convert such alterity into a universal, as if in order to redeem the feverish feeling–which was all the more feverish as it appeared paradoxical–of our historical precariousness.

8. Nothing very different happens today when, to use Edward Said’s expression, “the almost decorative weightlessness of history” in the age of postmodern consumerism becomes intertwined with a critical consciousness that is more highly developed than ever. On one point, however, the Islamophilic combat of the nineteenth century does belong to the past: that of a reinvention of European consciousness, located at the junction of social life and inner life, through the achievement of a new balance in decorative form–a utopian horizon whose decline today has turned the arts of Islam over either to the still quite vigorous projections of Orientalist fantasies or to the fine-tuned exercise of scholarly knowledge within the closed circle of museums: in France, the Louvre or the Quai Branly Museum, though no longer the Museum of Decorative Arts.

Bibliography

Brague, Rémi. Europe, la voie romaine. Paris: Gallimard Folio, 1999. Original ed., 1992.

Discovering Islamic Art: Scholars, Collectors and Collections 1850-1950. Ed. Stephen Vernoit. London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2000.

Irwin, Robert. For Lust of Knowing. The Orientalists and their Enemies. London: Allen Lane, 2006.

Jones, Owen. The Grammar of Ornament. Illustrated by examples from various styles of ornament. One hundred folio plates, drawn on stone by F. Bedford and printed in colours by Day and Son. London: Day and Son, 1856.

Oulebsir, Nabila. Les Usages du patrimoine. Monuments, musées et politique coloniale en Algérie (1830-1930). Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 2004.

Parvillée, Léon. Architecture et décoration turques au XVe siècle. Preface. Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc. Paris: Vve A. Morel et Cie, 1874.

Peltre, Christine. Les Arts de l’Islam. Itinéraire d’une redécouverte. Paris: Découvertes Gallimard, 2006.

Purs Décors? Arts de l’Islam, regards du XIXe siècle. Ed. Rémi Labrusse. Paris: Les Arts Décoratifs and the Musée du Louvre, 2007.

Quinet, Edgar. Oeuvres complètes. Vol.1. Le Génie des religions. Paris: Pagnerre, 1857. Original ed., 1841. (Reprint of chapter 2 of Book 2: Edgar Quinet, De la Renaissance orientale. Paris: L’Archange Minotaure, 2003.)

Redgrave, Richard. Manual of Design. Compiled from The Writings and Addresses of Richard Redgrave, R. A., Surveyor of Her Majesty’s Pictures, Late Inspector-General for Art, Science and Art Department, by Gilbert R. Redgrave. London: Chapman and Hall for the Committee of Council on Education, 1876.

Riegl, Alois. Questions de style. Paris: Hazan, 1992. Original ed., 1893.

Roxburgh, David J. “Au Bonheur des Amateurs: Collecting and Exhibiting Islamic Art, ca. 1880-1910.” Ars Orientalis. Exhibiting the Middle East. Collections and Perceptions of Islamic Art, 30 (2000): 9-38.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978.

Schwab, Raymond. La Renaissance orientale. Preface. Louis Renou. Paris: Payot, 1950

Rémi Labrusse is a professor of Contemporary Art History at the University of Picardy. He supervised the exhibition catalogue for Purs décors? Arts de l’Islam, regards du XIXe siècle (Pure decors? Nineteenth-century views of the arts of Islam), which was presented in Paris at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Autumn 2007. He has also published Matisse. La condition de l’image (Paris: Gallimard, 1999) and Miro. Un feu dans les ruines (Paris: Hazan, 2004).