Home>What war for what peace? by Julie Saada

10.07.2025

What war for what peace? by Julie Saada

This article was originally published in “Understanding Our Times” n°3

Julie Saada is a Professor of Philosophy at the Law School.

The world�’s greatest power seems to be carrying out a revolution sought by a constellation of ideologues that combines neoreactionarism, autocracy and the acceleration of capitalism. For them, the war in Ukraine is the matrix of this new order, and its corollary is the annihilation of the values and beliefs of its enemies. Faced with the Russian threat, and no longer able to count on American support, Europeans are struggling to envision the return of war to their continent, and war itself as a form of politics. Heirs to modernity with its dream of a world without violence, they must nevertheless abandon their denial of war and choose between two objectives: peace through force, where war is the norm and peace the exception, or peace through law, where peace is the norm and war the exception.

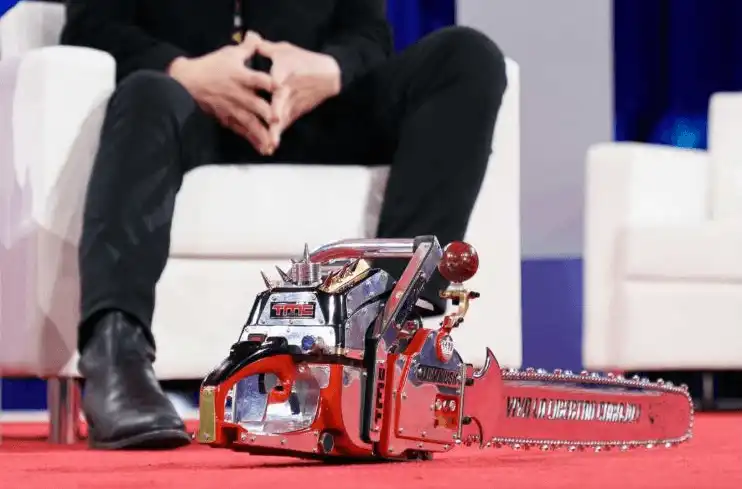

While Donald Trump may appear to be an irrational and therefore unpredictable player in both domestic and international affairs, after just a few months in office the decisions he has taken seems to follow a deliberate programme reflected in the writings of some of the ideologues in his entourage, namely JD Vance and Elon Musk. The radical nature of the measures imposed, in particular by executive orders, is striking. They have taken a ‘flood the zone’ approach, in the words of former Donald Trump adviser Steve Bannon. That is, they have saturated the media and political space to annihilate any reaction. At a domestic level, it is difficult for judges to block the many decisions taken that contravene US law, because they need the time to pursue legal procedures – the time that characterises the rule of law, as the political scientist and philosopher Bernard Manin underscored in his book on Montesquieu. At the international level, the thirst for possessing Canada, Panama and Greenland reflects a predatory imperialism which, as is the case domestically, jettisons rules – namely those of international law. The policy of the world's greatest power seems to have changed gears and produced the revolution called for by a constellation of ideologists, including Peter Thiel, Curtis Yarvin and Marc Andreessen (see box), combining neo-reactionary ideas, the promotion of autocracy as the only effective form of government (like a CEO running his company) and the acceleration of capitalism. The about-face on Russia has certainly been most striking to Europeans. Should we really be surprised?

War in Europe, or the Yarvin plan

A month before the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Curtis Yarvin, co-founder with Nick Land of the Dark Enlightenment movement, wrote that it behove Russia not only to restore order in Europe – with Trump's permission (if he returned to power) since the US is the greatest power – but also to take possession of it, so that ‘the Anschluss of Ukraine is a great idea.’ By ending US support for NATO and Europe more generally, Trump could encourage the development of authoritarian regimes within Europe. The war in Ukraine would become the matrix of this new order – paradoxically new and reactionary at the same time – in which nations, and certainly not confederations or unions like the European Union (EU), would form the only units of political communities. The political reversal would also, and primarily, be cultural. According to Yarvin, the first advantage of invading Ukraine would be to bolster Putin's image as the restorer of Greater Russia, thereby consolidating his power internally. The second advantage would be to allow Putin to govern a Ukraine that would then become post-European and post-liberal, ‘with traditional clothes, modern means of transport and an internet optimised with fibre-optic cables, but without porn, K-pop or gays’. Ideally, Russia would exert its power over Europe as far as the English Channel, in order to free it from liberalism and turn it into a ‘reactionary laboratory’ where lasting autocratic regimes would be established. For Trump, this would be a way of further increasing his power by weakening the State Department and the Pentagon, in a world where ‘there is no such thing as too much power.’

What is particularly striking in reading Yarvin and Thiel is their tendency to think of politics in terms of war. Yarvin calls for seizing power and victories that ‘must crush the deepest beliefs and presumptions of one’s enemies’, including those from within, particularly those of the administrative state. Meanwhile, Vance was in line with Thiel when he declared, at the Munich Security Conference in February 2025, that in the name of freedom of expression, regulations on platforms, artificial intelligence and data protection would need to be lifted. He argues that war would be waged in the digital world – a war in which not a single bullet is fired, but in which the damage can be colossal. The goal would be to destroy media organisations, bureaucracies, universities and state humanitarian aid, replacing them with a techno-oligarchy in the hands of billionaires driven by this neo-reactionary political imagination. Thiel went on to say that ‘Trump's return to the White House heralds the apokálypsis of the ancien regime's secrets’ and announced, as a warning of sorts, a future of ‘fresh and strange ideas’.

The denial of war

So what we should be astonished about is our own astonishment. It's as if war broke onto our political radar in February 2022, and even more so since, underscoring that we can no longer count on American support to counter the Russian threat. As historian Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau points out, this painful realisation casts the present in a tragic context, as war could directly affect us: it reflects our denial of war or our refusal of the reality of war. It appears that the reality of war had become alien to us. Not that it didn't exist, even in Europe: we need only recall the conflict in the former Yugoslavia or, earlier, the wars of decolonisation, starting with Algeria. But it no longer seemed to concern us. Since 1945 we have been building an international system designed to restrict war to legitimate self-defence and to provide a framework, under humanitarian law, for the actions that take place in war. The building of Europe also produced legal, economic and institutional arrangements that should guarantee peace and place war outside our political realm, at least within the European Union. According to the sociologist Hans Joas, we thus dreamt of a modernity free of all violence and, as a result, we have become incapable of thinking about war as a form of politics.

For Hans Joas, this dream is the very product of modernity: it is identified with it. In War and Modernity, he traces it back to the problem of war as portrayed by Hobbes. As early as On the Citizen (1642), and later in Leviathan (1651), Hobbes sought to found political science by deducing the conditions under which peace and security could be guaranteed. Only a strong power, the sole source of law, endowed with unlimited authority and inordinate potency, could put an end to the ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’ life that prevails in its absence. But this solution created a new problem. By guaranteeing internal peace, Hobbes prevented what could have produced external peace, that is, international peace. For the internal peace guaranteed by a powerful sovereign can no longer be guaranteed if that sovereign submits to a superior order (international law or super-sovereign) that limits its power. In other words, the conditions for internal peace become the conditions for international war. For Joas, it was this problem that the liberals wanted to solve. They did so both by conceiving of a republican liberalism of the cosmopolitical type (a confederation of free states, understood as republics, in Kant's conception) and by theorising a utilitarian liberalism (formulated by Montesquieu and Adam Smith) which recognises the costs of war and conceives of peace through trade. As a result, war came to be seen as a relic of an outmoded age that had not benefited from the European Enlightenment.

Hobbesian or Kantian peace?

Joas's thesis seems to ignore the awareness of war that emerged from major experiences of conflict, from the uprisings and integration of societies at war between 1793 and 1815, to the experience of combat in the Great War with the mobilisation not only of soldiers, but also of almost the whole of society, and to World War II, another total war, that included a genocide, the awareness of which slowly emerged. As Stéphane Audouin-Rouzeau points out, for those who lived through them, these acts of violence were a time that was irreducible to any other – an experience that must be understood as both collective and cultural. The breadth of what is understood by war, the fact that it cannot be reduced to the continuation of politics by other means, to quote Clausewitz, but must also be understood as a cultural reality, all contribute to this difficulty in defining it. At the same time, they demonstrate the magnitude of the phenomenon, not only in military terms but also in social and, more broadly, cultural terms. If the material experience of violence has been erased from our consciousness, it is perhaps because the common perception of war was at one time limited to its paroxysmal moments. By imagining war as great battles between regular armies, we formed a heroic, and therefore unrealistic, conception of it.

Joas's thesis is a fairly accurate description of our current awareness of war: the difficulty we Europeans have in feeling concerned by it, except when it directly threatens us. It also offers two models of peace that allow us to think about the meaning of war today. The first model is Hobbesian peace. It is precarious insofar as war exists not only in actual combat, but also in what Hobbes called ‘the will to engage in battle’. It is also an exception in an international context where war is the norm. International war continues even when countries are domestically pacified, held together by a strong power. The second model is that of perpetual peace developed by Kant in 1795 (and has experienced a contemporary revival). It makes peace the norm and war the exception. Kant believed that a coherent concept of peace must inherently include the idea of perpetuity, lest it be no more than a ceasefire or truce. He identified several types of peace: hegemonic or hierarchical peace, balance-of-power or polycratic peace, political union or federative peace, international or confederative law-based peace, and directorial or oligarchic peace. But Kant supported the coherence of a specific model: one in which the government seeks to serve the interests of the people, who have no interest in war. He linked peace to a confederate system of free states, governed by the rule of law, reflecting the interests of their citizens.

It remains to be seen which of the two paradigms – Hobbesian or Kantian – is the most coherent for Europe in a broader international configuration, as the denial of war dissolves and we leave behind the dream of a modernity without violence, as described by Joas. The Hobbesian model of a strong power that identifies freedom with security, could be the model of peace to which Putin aspires. This peace, like war, is neither constructed nor limited by law, because war must remain a prerogative of sovereign states in the name of their independence. It is peace by force. And this is how Yarvin sees war: it must be decided by states alone, in a world where it is not law that limits war, but war that is the source of law. From this perspective, human rights and humanitarian law are no more than a weakness of humanist minds incapable of understanding the irreducible nature of war and its uncontrollable violence (for Yarvin, however, conflict must be avoided to the greatest extent possible if its outcome remains uncertain).

The Kantian paradigm for peace, which is, in a sense, the intellectual inspiration for the Europe project, sees war as a last resort and an exception within a framework where peace through law is the norm. This conception is perhaps what led to our denial of war, to take Joas's perspective. But it is also the only one that we Europeans can hold on to – by awakening from the dream of a world without violence – if we do not want a temporary peace ensured by a great power, which can choose to shatter it at any time to increase its might and expand its territory. So the question remains: what means are we prepared to use to protect ourselves from a peace that would be no more than a truce – a peace held by force that would risk incubating another war?

Julie Saada (Agrégation, Ph.D. and Habilitation, Ecole Normale Supérieure of Lyon, 2004 and 2013) is a Professor of Philosophy at the Law School. Her work in the philosophy of international law focuses on the legal and ethical norms of war and the post-war era, as well as on international criminal justice and transitional justice.

Reference

- Arcidiacono, B. 2011. Cinq types de paix. Une histoire des plans de pacification perpétuelle (XVIIe-XXe siècles), Paris: PUF.

- Audoin-Rouzeau, S. 2023. La Part d'ombre. Le risque oublié de la guerre, Paris: Les Belles Lettres, pp. 14, 19.

- Holeindre, J.-V. 2018.‘Penser la guerre’, in B. Cabanes, T. Dodman, Hervé Mazurel, G. Tempest (eds.), Une histoire de la guerre. Du xixe siècle à nos jours, Paris: Seuil, pp. 37–48.

- Joas H. 2000. Kriege und Werte. Studien zur Gewaltgeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts, Weilerswist: Velbrueck; War and Modernity, 2003. trans. R.

- Livingstone, Cambridge/Malden: Polity Press and Blackwell.

- Keegan, J. 2019. History of War. From the Neolithic to the Gulf War, Penguin.

- ’L'apocalypse de Donald Trump selon Peter Thiel’, Le Grand Continent, 10 January 2025.

- Miranda, A., 2025. ‘Curtis Yarvin, Ideologue of Trumpism and the End of Democracy’, The Conversation.

I would like to thank Arnaud Miranda for his comments on my article.

The Sciences Po's Research Magazine