A question is being raised more and more often these days: How far must one go to know a thing? Is one to open it up to the point of imagining that one can touch its “essence” or else, on the contrary, is it better to remain on the surface while investigating its most superficial traits? In a study of perfume bottles, Richard Stamelman recalls the major role played by Francis Ponge, who forged new words in order to reinvent one’s attention to things: the objeu (the object-game) and the objoie (the ob-joy). He, too, gazes at objects with curiosity: all those bottles that attract our attention in the name of a promise of content that remains secondary.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac.

Richard Stamelman “Objeu” and “Objoie” in a Perfume Bottle

A question arises concerning our knowledge of objects and the study of their everyday, practical, historical, social, psychological, or philosophical nature. Should we deepen things, penetrate them down to their “very substance,” descending layer by layer until we reach their innermost center, in order to discover therein their essence? Or should we remain, rather, at an object’s surface, surveying its space all the way to its horizon, following its sinuous meanderings and remaining attentive to its to-and-fro movements while investigating its most superficial traits? Italo Calvino would have opted, it seems, for the surface, where the profound complexity of an object would have the greatest likelihood of being unveiled: “behind every displayed object [there is] the presence of the civilization that has given it form and takes form from it.”[1]

For Francis Ponge, the reality of the world was not only “behind every displayed object” but within. Although Ponge had composed so many prose poems—or “proems,” as he preferred to call them—concerning natural objects and objects of human invention, all of them familiar, he never investigated, alas, the perfume flask. Investigating really is the right word here. For, Ponge scrutinized and dissected the object of his contemplation in a mise-en-abyme designed—without his ego intervening to overly humanize and therefore distort the description— to become the witness for the object and its spokesperson. What is of special interest in the objects that attracted him is the quality of “their presence, their obvious solidity, their thickness, their three dimensions, their palpability, indubitability, their existence of which I am far more certain than of my own.”[2] Seeking to see the object from within and to gaze upon it from the perspective of its thinghood, he succeeds in enumerating the particular qualities that endow the object with its singularity, to the point that the “partisanship of things [le parti pris des choses],” as he called it, would be expressed through the “consideration of words [le compte tenu des mots]” or through the “gaze-such-that-we-speak-it [le regard-de-telle-sorte-qu’on-le-parle].”[3] In search of the unique sensitive cord buried within each thing, an instrument that sings out its particularity, the poet-miner descends into the lower depths of the object in order to traverse its subterranean tunnels in the hope of discovering there this chord and making it vibrate. Thus, the mute object, upon which no one has ever truly gazed from its own point of view, rids itself of its muteness and speaks with the words the poet lends to it. Making an object resound means making an object speak, injecting language into it in order to bring it to revelatory expression.

Ponge envisages the invention of a new genre of poetic description and definition, which he names the objeu, the object-game. The phenomenon of the objeu sheds light on the activity the object experiences when, with vitality and independence, it gives itself over to a language game that is also a game of self-expression. By means of this game, an object comes back to life in language, exits from the shadows of insignificancy, tears down the walls of silence that enclose it, and ends up making itself signify. “Objeu” is not the only neologism Ponge invented. There is also the objoie, the ob-joy. Ponge sees the objoie as a prolongation of two experiences: that of the object, as defined by its status as a pro-ject, a pro-jection, a projectile, and that of the objeu, where the intense energy of the game, driving words to gambol about, to play, and to enjoy [jouir], creates joy, jubilation, enjoyment [jouissance] and yields, in addition, an important moral lesson.

The perfume bottle and the perfume, which the glass walls of this flask surround, embody, in my opinion, the sensorial aspects of the Pongian objoie and objeu. One has only to look at the ads for Chance, the fragrance Chanel launched in 2002 in a round flask, to find a perfect example of the staging of the objoie and the objeu. Chanel’s advertising film shows a young woman bounding vigorously toward a gigantic flask not only to kiss it but to sweep into it, to become one with it. A series of other advertising spots accentuating the key role chance plays in sports encourages players to take risks in such games, that is to say: “Take a Chance—Take a Chance on Love.” The daring and mischievous woman who, by dint of seizing “fleeting chance” and therefore of committing herself to playing the game and winning it, expresses “how much CHANCE is a fragrance of optimism and independence.”[4] What is amazing in these advertising spots is the spirit of impulsive but charming joy expressed by the models, who use the flask as a bowling ball or to play a game of soccer.

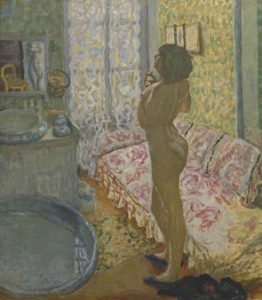

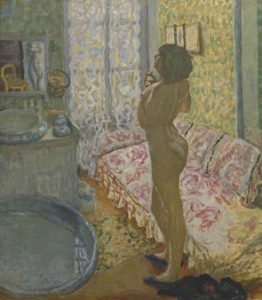

In a canvas executed by Pierre Bonnard that was completed in 1908 and entitled Nude Against the Light, Bonnard’s mistress, Marthe de Méligny, steps out of her bath. What, in my opinion, this canvas represents is the radiant glorification not only of the Woman but, more essentially, of perfume and its bottle. Here one sees the triumph of what the poet Pablo Neruda, overwhelmed by the elemental power of objects, describes as “the sumptuous appeal of the tactile”—a tactility that makes one think of the palpable quality of every Pongian object.[5]

Pierre Bonnard, “Nude Against the Light”, oil on canvas, 124.5 cm x 109 cm (ca. 1908),

© Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels.

[Photography from Jean-Louis Mazieres.2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) https://www.flickr.com/photos/mazanto/16137025766/]

Bonnard’s canvas is divided vertically into two parts whose light and decor differ radically. On the left, everything is gray, drab, washed out. One sees a bathtub filled with murky water, a somber bathroom cabinet, a wall with faded wallpaper, and a mirror in which the pale and fragmented reflection of the nude torso of Marthe is a ghostly white. This is all the more striking because, on the right side of the canvas, her body, fully sculptural and enveloped in a powerful light, appears to be the apotheosis of dazzling femininity. This right side—bursting with beams of light [rayons] that pierce both the windows and the semitransparent curtains, and which make the red patterns of the couch, as well as those of the yellowish wall, shine forth—bathes Marthe in a splendor of light that brings out the beauty and youth of her body. What a great contrast with the drab half of the painting! Marthe seems to offer herself to the pervasive bright light. With her dramatically bent back, which brings out the curve of her upper body, and with her shoulders pushed backward, Marthe joyously and proudly welcomes the sun entering the room. And the slightly protruding pose of her hip and the raised position of her head and of her neck testify to a forcefulness and a confidence, which signal that this woman does not bow before the sun but, instead, considers herself to be its equal and, perhaps, even its rival. Her movement in exiting from the bath prepares her for the rite of exalted sublimation that will crown her body and surround her with a halo of bright sunlight [rayons] which at the same time will envelop her in the light [rayons] of perfume.

This is because the most important object on the right side of this image, a thing whereby the rays are centered, focused, and become crystallized into a luminous and golden node (that is to say, the element that serves as intermediary between the woman’s corporeal humanity and the divine splendor of the light), is the perfume bottle from which glistens a yellow flash of light, and which Marthe’s right hand proffers to the sunlit window. The flask is the mediator between Marthe and the light: it is, to use an English word, the go-between that mediates the connection between woman and world, body and air, flesh and spirit, skin and vapor, opacity and transparence, sensuality and luminosity, and sense and essence. The flask is transformed into a sun whose perfume, once having permeated the air, fills it with rays and effusions golden and fragrant.

What Bonnard has succeeded in doing is to represent a solar flask from which emanates both a perfumed luminosity and a luminous perfume. This representation of light born of scent, has been celebrated by artists—such as Luigi Russolo, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dali, Alberto Giacometti, Louise Bourgeois, and Françoise Quardon—as well as by poets—Charles-François Panard, Charles Baudelaire, and Stéphane Mallarmé—all of whom are examined in the present paper.

As the bottle designer Sylvie de France has observed, a perfume flask is “a tiny loquacious [bavard] bit of architecture.[6] Whether “talking” loudly or “whispering” sotto voce, it speaks in a “language” of glass, clay, metal, enamel, plastic, leather or other heterogenous materials, or through poetically evocative names, or in ingenious forms of sculpted glass, all of which are designed to evoke love, passion, femininity, Frenchness, great historical events, as well as small trivial objects of everyday use. According to the perfumer François Coty, perfume has to “attract the eyes as much as the nose.”[7] From fin-de-siècle perfume bottles that the evanescent spirit of the Art Nouveau movement fashioned into flowing, vibratory, and organic shapes, to Art Deco flasks of the 1920s and 1930s with their strictly geometric, streamlined contours, our study will describe a trajectory that ends with the chic and extravagant flasks of our own time. This journey shows the degree to which the imaginary of perfume bottle design, insofar as it displays a varied constellation of symbols, signs, styles, figures, visualizations, narratives, and references, seeks to evoke historical realities, cultural habits, and powerful ideologies that float in the air of a given society.

[1]Italo Calvino, Mr. Palomar (1983), trans. William Weaver (New York: Harcourt, 1985), p. 73.

[2]Francis Ponge, “My Creative Method,” in Méthodes (Paris: Gallimard, 1961), p.12. [Translator: An excerpted version of Beverley Bie Brahic’s English-language translation, including this phrase, appears here: http://maisonneuve.org/article/2002/11/18/my-creative-method/].

[3]Ibid., pp. 20, 22. [Translator: This English-language translation is suggested by Anne A. Davenport, translator of Jean-Louis Chrétien’s The Call and the Response (New York: Fordham University Press, 2004), p. 38.

[4]Coup de foudre à Venise. Une aventure signé Jean-Paul Goude, Chanel press packet (Paris, no date or pagination).

[5]Pablo Neruda, “Toward an Impure Poetry,” in Five Decades: A Selection. Poems 1925-1970, trans. Ben Belitt (New York: Grove Press, 1974), p. xxii.

[6]Sylvie de France, “Sylvie de France, Designer,” interview with Sylvie de France, Fragrance Foundation, France, p. 2: www.fragrancefoundation.fr/education/sylvie-de-france-designer (accessed July 24, 2018).

[7]Elisabeth Barillé, Coty: Parfumeur and Visionary, trans. Mark Howarth (Paris: Assouline, no date), p.101.

Selected Bibliography

Atlas, Michèle, and Alain Monniot. Guerlain. Les flacons à parfum depuis 1828. Toulouse: Editions Milan, 1997.

Blanchot, Maurice. “Everyday Speech.” The Infinite Conversation. 1969. Trans. and Foreword Susan Hanson. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Baudrillard, Jean. The System of Objects. 1968. London and New York: Verso, 1996.

Baudrillard, Jean. The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures. 1970. London and Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998.

Bodei, Remo. The Life of Things, the Love of Things. 2009. Trans. Murtha Baca. New York: Fordham University Press, 2015.

Brown, Bill. Other Things. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Fellous, Colette. Guerlain. Paris: Denoël, 1987.

Mitchell, J. T. What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Sheringham, Michael. Everyday Life. Theories and Practices from Surrealism to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Stamelman, Richard. Perfume: Joy, Obsession, Scandal, Sin; A Cultural History of Fragrance from 1750 to the Present. New York: Rizzoli, 2006.

Thuillier, Guy. L’imaginaire quotidien au XIXe siècle. Paris: Economica, 1985.

Richard Stamelman , a former professor of French and Comparative Literature at Wesleyan University and Williams College, is a specialist in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century French Poetry. He has authored studies on Charles Baudelaire, Guillaume Apollinaire, André Breton, Pierre Jean Jouve, Francis Ponge, Philippe Jaccottet, Yves Bonnefoy, Edmond Jabès, Alberto Giacometti, and Claude Garache, among other French poets and artists. He is also the author of Drama of Self in Guillaume Apollinaire’s “Alcools”; Lost beyond Telling: Representations of Death and Absence in Modern French Poetry; Perfume: Joy, Obsession, Scandal, Sin; A Cultural History of Fragrance from 1750 to the Present; and editor of Yves Bonnefoy, The Lure and the Truth of Painting. Selected Essays on Art. He is a knight of the French Order of the Academic Palms.