Prudence Bidet studies the albums of Yoko Ono, who mixes everything together: music, politics, and autobiography. Less studied than the rest of her creative work, these singular objects, especially her first solo albums, contain strong symbolic charges while displaying her desire for liberation. In her fourth album, in particular, Feeling the Space (1973), she pays homage to women by encouraging them to take action through images, words, and sounds.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Hartung-Bergman Foundation Seminar

The Feminist Albums of Yoko Ono:

Ambivalent, Political, and Autobiographical “Things”

Prudence Bidet

Yoko Ono is a prolix artist, and yet her most accessible works paradoxically are those least studied. Her first solo albums, personal and political in nature, are multidisciplinary objects as well as bridges between her sound work, her visual-arts works, and her literary creations. Through various levels of reading, we may see that they offer a synthesis for her recurrent set of themes.

Musical Education

In her youth, Yoko Ono moved within a quite varied sound world. Her father, influenced by Western music, taught her the piano while she also took singing classes, from the great arias of classical opera to Romantic lieder. Education in learned European music was an obligation for young Japanese girls, who were also trained in the practice of calligraphy, dance, and the art of tea. Her musician mother handed down to her the rules of writing and composition connected with traditional Japanese music.

This dual heritage served to develop her musical bilingualism. When her family left Japan for the United States in 1952, she entered Sarah Lawrence College and discovered there the learned music of the twentieth century—Schoenberg and Webern—as well as the singing technique of Sprechtgesang (spoken singing). She gradually developed a vocal practice of her own that drew on the European operatic style and the Japanese hetai technique from kabuki theater (irregular and highly jerky vibratos, with quite large fluctuations in sound between low and high pitches). The intensity and the expressiveness of this practice are due especially to the physical involvement of the singer that this practice demands; the singer has to force her voice out from the throat, and the pain, often unavoidable, comes to garner empathy from the listener. The idea is to get one to hear what the artist produces as well as the physical effort required. Self-control and self-mastery have to be visible for the singing to be expressive.

First Sound Creations

Ono married in 1955 and settled in New York. There, she met John Cage and LaMonte Young, with whom she organized various events in her loft at 112 Chambers Street between December 1960 and June 1961. In that loft, she presented her first visual-arts works but also her first sound things, musical instructions, which she published in 1964 in Grapefruit, a set of instructions. At once graphic and conceptual, her first scores granted as much importance to words as to notes, to the point of eventually becoming exclusively literary in character: instructions in haiku form. Ono proposed there that one transform noises into sounds, and she shared with Fluxus the idea of an art of the everyday: all things (objects or events) have an aesthetic interest.

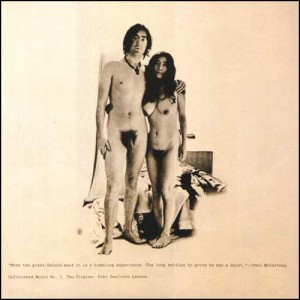

Unfinished Music n°1: Two Virgins. 1968. Front Cover. Apple Records. All rights reserved: Yoko Ono-Apple Records.

She met John Lennon in 1966. As a couple, they fully became a work of art, and their meeting signaled the beginning of a highly intense musical and artistic collaboration. The first three Yoko Ono albums, experimental in nature, were coproduced by Lennon, while their first joint album, Two Virgins, was censured at the time of its release, its cover showing to the public these artists’ bodies completely unadorned.

Dualities

Ono’s first solo album, Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band, is experimental and, above all, instrumental. It was executed at the same time as Lennon’s John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, in 1970, with the same group and the two of them again sharing the cover: the two artists are stretched out on the grass, in harmony with nature, a new reference to Genesis and to their first album as well as to the complementarity of the sexes.

Fly, which was released in 1971, was directed and designed entirely by Ono, accompanied by Eric Clapton and Lennon. She organized her album in two parts. The first part is devoted to dance songs written in a rock-‘n’-roll style and associated with Yang; the second is organized around a rather complex numerical system associated with Yin. Each song was assigned a number, with each number referring to a body part. This procedure was inspired by that employed by early twentieth-century twelve-tone composers and expressed in an explicit way Ono’s desire to produce a double album, for body and mind, the masculine and the feminine. This search for balance and complementarity is a recurrent theme in her visual-arts work and is not the only point of contact between Fly and her earlier works. The title of the album references three of her other creative works. The first is an instruction from 1963: “Fly Piece: Fly.” The artist invites one to be free, and the imagination becomes a tool to escape the human condition, more specifically that of oppressed womanhood. Woman is the subject of one of her films, Fly (1970), done with Lennon: a fly flies above the motionless body of a woman for 25 minutes. The soundtrack is none other than the track “Fly,” published on her eponymous album; Ono’s voice, recorded backwards, imitates the fly’s flight. The artist is symbolized both by the woman being offered for our view and by the fly, which finds its freedom by taking off out the window. Her emancipatory investigations achieved success in December 1971, when Ono organized her virtual exhibition at the Museum of Modern [F]art. She announced in the press a One Woman Show at MoMA. The event did not take place, but the artist published a catalogue in which she presented her virtually exhibited works, including a giant jar containing nothing but flies.

Fly,1971. Front Cover. Apple Records. All rights reserved: Yoko Ono-Apple Records.

The cover of the first album is both a portrait and a calling card. Executed by George Maciunas, a Fluxus artist, it fragments, like the camera in Fly, Ono’s body by showing her leg dressed in a stocking and her face. Her face is to be found again on the jacket, on the vinyl disk, and on a poster contained within the album, where Lennon also figures. These three levels of representation form a triptych that has creative woman as its subject while highlighting her different personas: avant-garde artist close to the Fluxus movement, pop-culture icon, new celebrity. Her face thus becomes a motif, and it is to be found again on her increasingly political solo albums that followed this first one.

Mirror Albums

In 1972, Some Time in New York City, coproduced by the Ono-Lennon couple, was ill received by critics as well as by the public on account of its political content. Ono was accused of manipulating Lennon, of instigating their activism, and above all she was presented as castrating, an opportunistic “wife of.” While the artist suffered from this reception, she took these criticisms up again to her own advantage and reused them, the better to expose them.

Approximately Infinite Universe. 1973. Front Cover. Apple Records. All rights reserved: Yoko Ono-Apple Records.

Approximately Infinite Universe was released in January 1973. Its main subject is male/female inequalities and the malaise they engender. Ono expressed herself here in the first person, told stories in the manner of short tales, and used the expressiveness of her voice to render audible the pain of her characters, most of them female. She made herself the spokesperson for suffering women, used her vocal technique to get one to hear their physical ordeals, and showed her face once again on the cover, as a sort of signature.

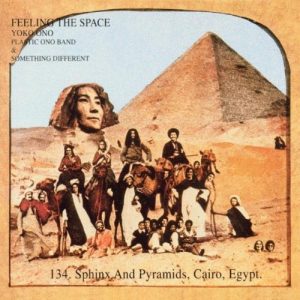

Feeling The Space. 1973. Front Cover. Apple Records. All rights reserved: Yoko Ono-Apple Records.

It was also on the eve of separation for the Lennono couple that the singer paradoxically recuperated her image as mysterious black widow in Feeling the Space, which was released in November 1973. Overtly feminist, this fourth solo album was dedicated to women who had died of pain and sorrow or were interned for having opposed the patriarchal order. With a greater or lesser degree of irony, Ono mentions here witches, bad wives, and women who have been cheated on while offering, with “Woman Power,” a hymn to revolution as an echo to her political manifesto, “The Feminization of Society,” which appeared in 1972 in the New York Times. For the cover, Ono did a montage in which she appears within two distinct space-times: head of a caravan, female man-leader, she also replaces the head of the Egyptian Sphinx with her own face. The artist gives monumental dimensions to her portrait and sees to her posterity while anchoring herself in collective memory as a mythological and timeless being. This magical dimension, more benevolent than wicked, is to be found again on the rear of the record jacket: Ono did a montage that reproduces the image of her eye, a demiurgic and creative eye. She once again fragments her body in order to play with the mystery surrounding her media persona.

A Corporeal, Aesthetic, and Political Engagement

In 1964, Ono presented Cut Piece, her most famous work. In this performance, she remains motionless on stage, and the audience is invited to come forward and cut her clothes with the help of a pair of scissors. The minimalist form of this polysemic creative work foregrounds the gift of the artist’s body, the vulnerability of women’s bodies, and the decisive role played by the audience. Self-mastery and passivity tend to merge in a way that serves to denounce the reification of women’s bodies. While posterior to Cut Piece, the other albums all have points of contact with that work and can be perceived as prolongations in sound and iconography of her bodily act. Fly presents Ono as a conceptual, avant-garde artist. Approximately Infinite Universe brings out the symptoms of a patriarchal, violent, and inegalitarian society. Feeling the Space drives women to action and calls for revolution. The feminist message carried by Ono is intentionally made accessible through the choice of a format and a popular-music style that promotes an art for all. The efforts at empathy and dramaturgy she performs resonate, too, with her universalist conception of aesthetic and, still more, sonorous experience, which is based on a necessary complementarity between conceptualization and feeling. Pieces of one and the same puzzle, all of Ono’s albums possess a “family resemblance.” Singular works, they are also connected together by a play of references that reveals the homogeneity of her multidisciplinary work, which is still ongoing.

Bibliography

Cott, Jonathan, and Christine Doudna. Eds. La ballade de John and Yoko. Paris: Denoël, 1982.

Haskell, Barbara, and John Hanhardt. Yoko Ono Arias and Objects. Salt Lake City: Gibbs-Smith Publisher, 1991.

Iles, Chrissie, and Yoko Ono. Eds. Yoko Ono: Have You Seen the Horizon Lately? Oxford: Museum of Modern Art, 1997.

Munroe, Alexandra, and Jon Hendricks. Eds. Yes: Yoko Ono. New York: Japan Society and Harry N. Abrams, 2000.

Ono, Yoko. “The Feminization of Society.” The New York Times, February 23, 1972. http://www.nytimes.com/1972/02/23/archives/the-feminization-of-society.html

Pfeiffer, Ingrid, and Max Hollein. Eds. Yoko Ono: Half-a-Wind Show—A Retrospective. Frankfurt: Prestel, 2013.

Raspail, Thierry. Ed. YOKO ONO: Lumière de l’aube, Lyon: Somogy, 2016.

Prudence Bidet, who has a degree in Musicology, was trained classically in percussion at the Conservatory of Angers. After receiving her graduate degree and then a Master of Research degree in the History of Art, her investigations have borne on the bodies of women artists as both creative and creations in their own right, tools as well as productions. Her research is currently focused on the issue of the body and of its staging, specifically on the work of Diane Torr, a performance artist who began the Drag King movement, and on that of Yoko Ono.