Home>World Elite Database: Comparing Economic Elites on a World Scale

16.05.2025

World Elite Database: Comparing Economic Elites on a World Scale

A collaboration of around 70 researchers in social sciences, including Bruno Cousin, FNSP professor at the Center for European Studies and Comparative Politics (CEE), has created a global database on economic elites (“World Elite Database”, WED) currently comprising of 16 countries, including France. Its structure, based on common criteria, truly allows for the first time to compare economic elites in very different national contexts.

The first results of this international research program have just been published in The British Journal of Sociology.

A map covering 16 countries

To map economic power as comprehensively as possibly, the elites included in this database are those who run the largest companies in each country, possess the greatest fortunes, and/or are in a position to influence the rules of the economic game (certain ministers and senior officials, and the heads of major asset managers, interest groups, consulting firms, invest banks, and corporate law firms).

After 3 years of work, more than 3,500 individuals in total have been identified in the 16 countries studied, each with several biographical details, allowing for comparisons of their profi les. The database currently covers 16 countries on 4 continents (Europe, North America, South America , Asia), representing 33% of the world’s population, 54% of the global GDP and 74% of billionaires.

First results: age and gender

The first results suggest that economic elites do not form a homogeneous group, and some major trends can already be identified. Unsurprisingly, those exercising economic power are often male, older, born in an economic capital, and have a higher level of education.

The United States however has the oldest economic elites in the sample (median age of 62), while China and Poland have the youngest elites (median ages of 55 to 55.5), perhaps because these countries have more recently joined the globalized economy.

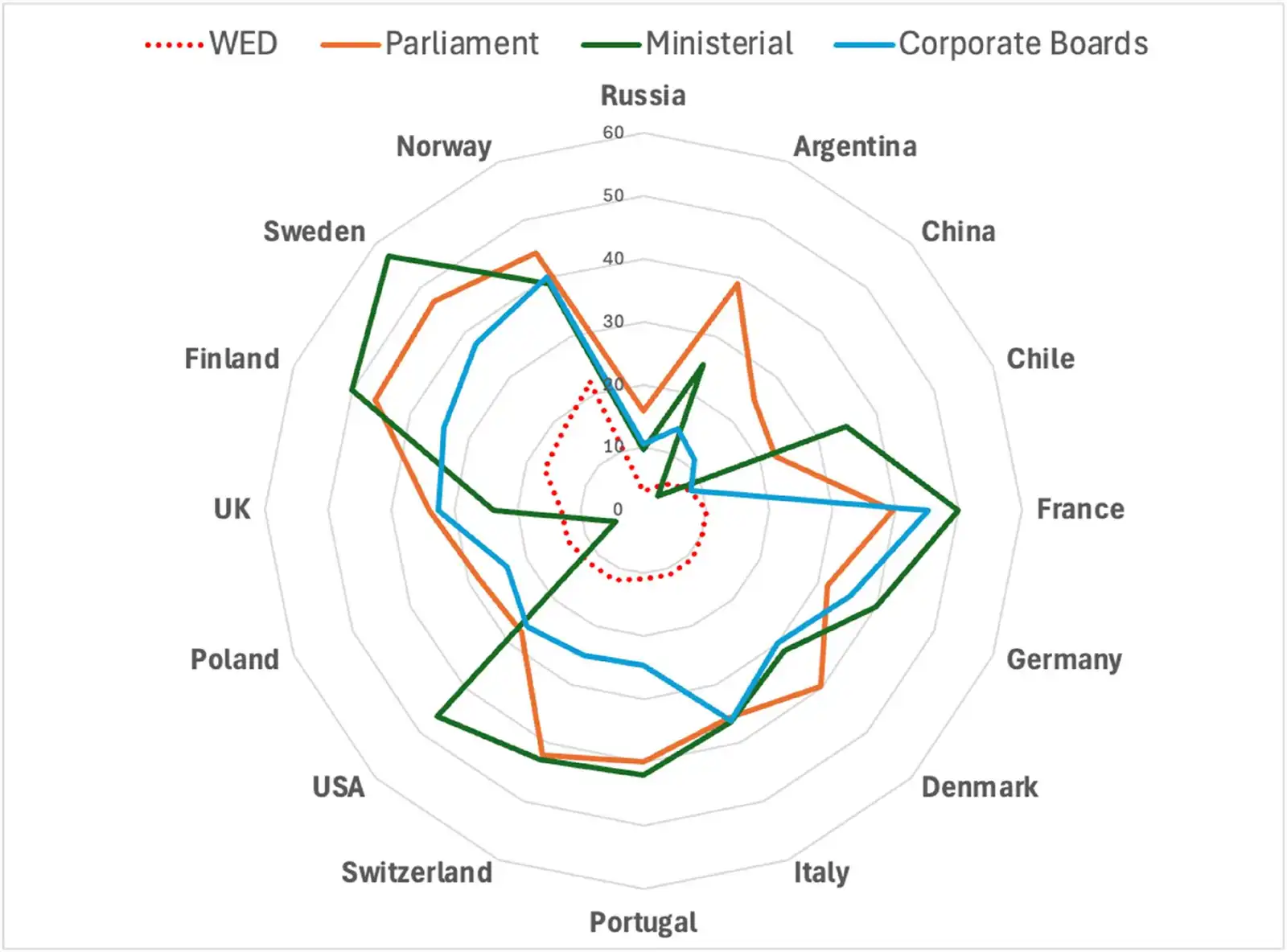

Economic elites are still less feminist than political elites. And, since the WED is made up of the “top” economic elites (notably corporate CEOs), the gender imbalance is even more pronounced than on corporate boards. Proportion of women among

The importance of birthplace and education level

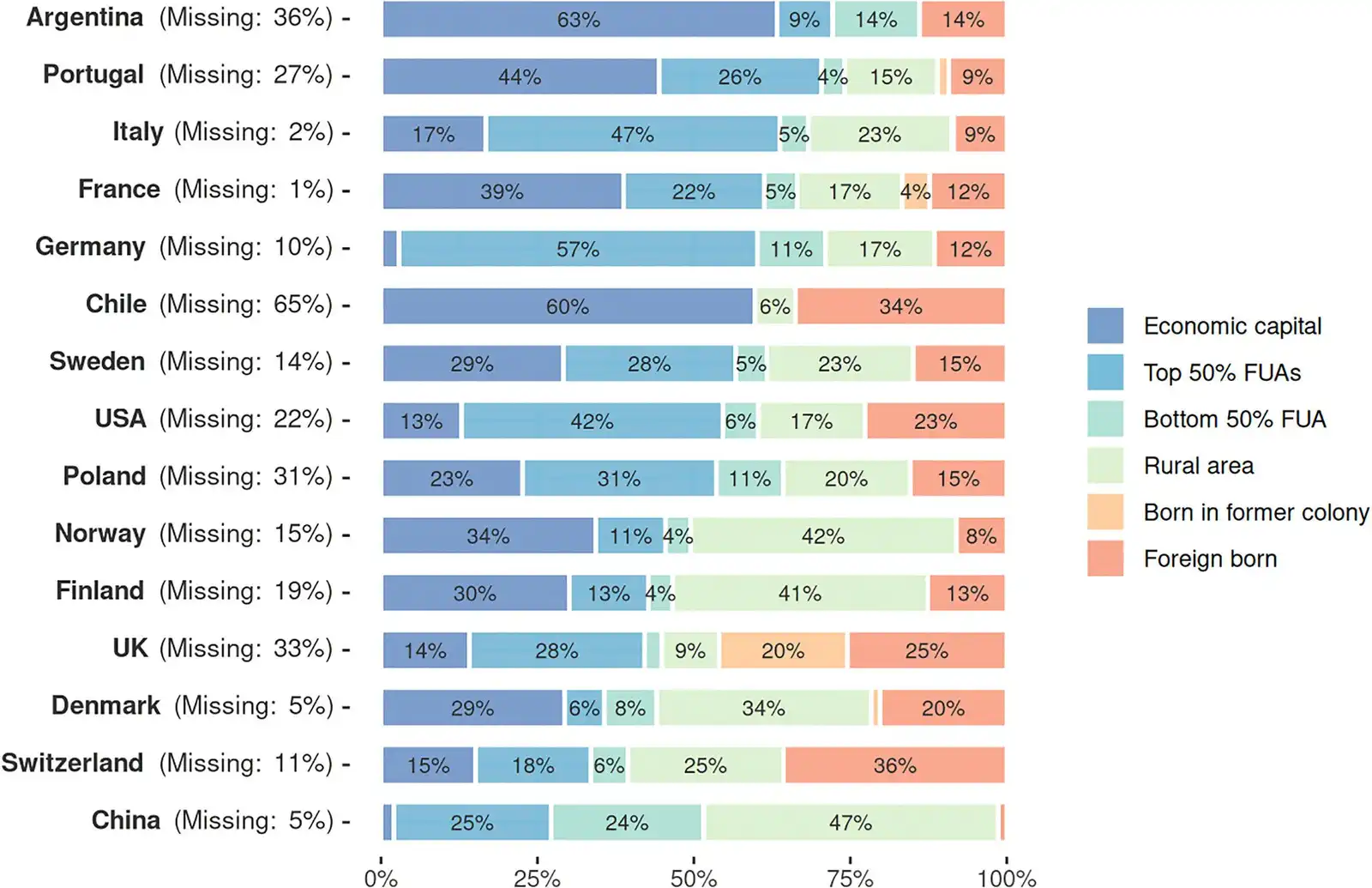

Despite globalization, the majority of these top elites were born in the country of the organization that they lead. And being born in the economic capital can be a considerable advantage, notably in France (where this is the case for 39% of elites, compared to 13% in the United States, 14% in the United Kingdom and 17% in Italy).

Switzerland and the United Kingdom stand out for their significant proportion of foreign-born elites, while this proportion is virtually non-existent in China.

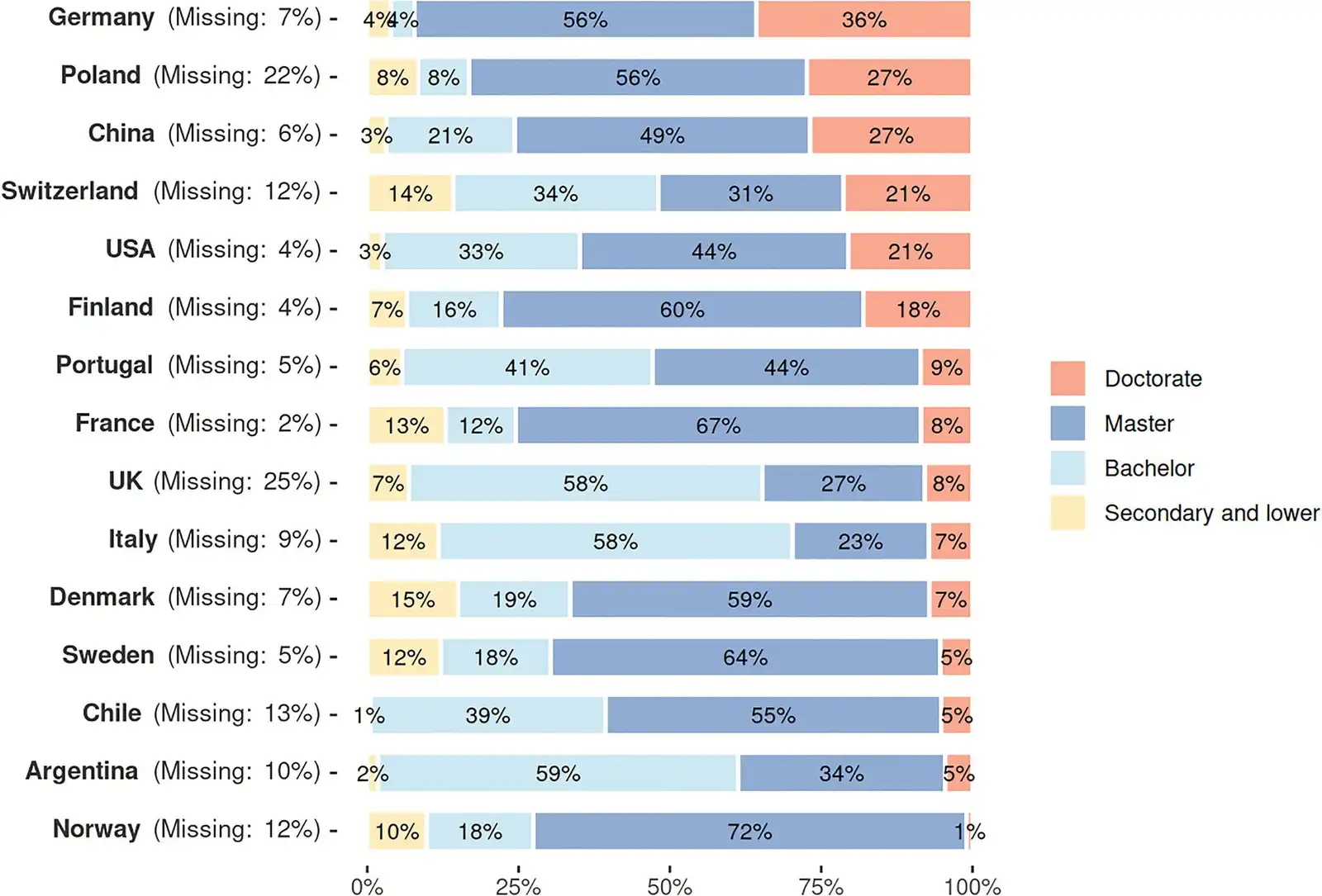

Levels of education also vary: while a master’s level predominates in most countries including France (where the “grandes écoles” prevail), a bachelor’s level is the majority in Argentina, in Italy and the United Kingdom.

In Germany, 36 % of economic elites hold PhD degrees, 27% in China, 21% in the United States, but only less than 10% in the rest of the countries studied (8 % in France).

As for the majority field of study, it is, of course, business, surpassed only in China and in Finland by engineering studies.

The World Elite Database teams will exploit this data in more detail, while still conducting regular updates . They are also in the process of integrating additional colleagues in order to cover more countries.

Translation from French to English by Hannah Ashburn

References

- Website of the WED (World Elite Database) collaboration: worldelitedatabase.org

- The academic article published in The British Journal of Sociology (open access): Varieties of Economic Elites? Preliminary Results From the World Elite Database (WED), Felix Bühlmann, Caroline Ahler Christesen, Bruno Cousin, François Denord, Christoph Houman Ellersgaard, Paul Lagneau-Ymonet, Anton Grau Larsen, Mike Savage, Sylvain Thine, Kevin Young, Pedro Araujo, Paola Arrigoni, Jorge Atria, Pierre Benz, Johanna Behr, Maria do Carmo Botelho, Asif Butt, Pedro Casanova, Luís Clemente-Casinhas, Ana Castellani, Fabio Cescon, Joselle Dagnes, Hanna Debska, Anne-Sophie Delval, Vitalina Dragun, Andreia Egas, Kajsa Emilsson, Xiaoguang Fan, Fan Fu, Julia Gentile, Orlando Gomes, Victoria Gronwald, Mariana Heredia, Johannes Hjellbrekke, Jorge Honório, Jie Huang, Johnathan Inkley, Håkan Johansson, Ilkka Koiranen, Aki Koivula, Hanna Kuusela, Gabriel Levita, Chao Ling, Peng Lu, Michael Lukas, Jacob Lunding, Mina Mahmoudzadeh, Sean McQuade, María Luisa Méndez, Nuno Nunes, Shay O'Brien, Gabriel Otero, Marta Pagnini, Alejandro Pelfini, Jéssica Pereira, Catalina Roa, Thierry Rossier, Marte Lund Saga, Dulce Santana, Christian Schneickert, Elisabeth Schimpfössl, François Schoenberger, Izaura Solipa, Łukasz Trembaczowski, Maren Toft, Sofia Vale, Pedro Vasconcelos, Jorge Quesada Velazco, Tomasz Warczok, Xinguo Yu. The British Journal of Sociology, First published: 27 March 2025. DOI: 10.1111/1468-4446.13203

(credits: Shutterstock / Dilok Klaisataporn)