Victor Claass’ interest in billiards came from his reading of Michael Baxandall’s work on “influence”, and the use of the game as a metaphor. The English art historian upends the causal conception of the art world in order to put forward a new paradigm : the game is more open than we thought, artists are not “influenced”, but carom in a vast space made of exchanges, borrowings and reuse. In order to rewrite art history, they converse with other works, beyond the boundaries of time and space ; Degas is haunted by the image of the pool table, not so much by love of the game, but because it raises in him the specter of the hurdle as well as the feeling that in painting, one must always start over.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac.

Victor ClaassObject ball

“The sides of this venerable oak billiard table opened like a cupboard

and could have held a small military avant garde”

Champfleury, La succession Le Camus. Misères de la vie domestique, 1857

Digression on a digression

In his 1985 work Patterns of Intention, art historian Michael Baxandall invited the scientific community to rethink the way it understood works of art. It is a particularly dense and technical text, born from a theoretical investigation by the author of the idea of “intention” and which questions the oft problematic way art historians have sought to interpret it. The book, a landmark example of epistemological questioning for the discipline, features a small excerpt that is so unexpected it deserves to be highlighted: in it, the author builds a curious analogy between art history and billiards.

In this oft quoted excerpt, titled “Excursus against influence”, Baxandall believes it is necessary to remove the tricky idea of artistic ‘influence” from the theorical toolbox of the art historian. Weak, ill-used, for him this word perpetuated a causal conception of how forms relate to one another, which he chooses to compare to the transfer of kinetic energy when one ball collides into another during a pool game. “The classic Humean image of causality that seems to colour many accounts of influence is one billiard ball, X, hitting another, Y”.1M. Baxandall, Patterns of intention: on the historical explanation of pictures, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1985, p. 60. To counter what he deems a simplistic model, Baxandall argues for a change in focus. To him, the story of artistic development, with all that it entails of appropriations, exchanges, borrowings, breakthroughs, setbacks and blows – themselves relying on an immeasurable plurality of causes -, took place on a wider field, for which a pool or a snooker table, where brightly colored spheres knocked into one another, seemed an apt visual. The author concluded: “Arts are positional games and each time an artist is influenced he rewrites his art’s history a little”.2M. Baxandall, Patterns of intention, p. 60. Emerges then, through consecutive crashes, a social and artistic map of creation that is ever changing, and defined by its infinite possibilities, its misses and temporary concealments, its laws and its coincidences.

Observing, playing

Antoine Trouvain (1656-1708). “Troisième appartement à Versailles – Le Roi, Monsieur, Monsieur le duc de Chartres… jouant au billard”. Gravure. Paris, musée Carnavalet.

Applied literally, playfully even, this metaphor invites us to observe the various, surprisingly frequent, occurrences of billiards in the history of visual arts. The game emerged, in its modern table-based shape, in the fifteenth-century and stood out by being played throughout the European courts. Famous images, notably an engraving by Antoine Trouvain (fig. 1) representing Louis XIV playing with his ministers, document the way billiards allowed to act out “individual or collective confrontations, be they amorous or belligerent”,3H. Damisch, ‘L’échiquier et la forme “tableau”’, in Lavin I. (ed.), World Art: Theme of Unity in Diversity, University Park, Pennsylvania, State University Press, vol. 1, 1989, pp. 187-191 as described by Hubert Damisch when discussing chess. Long associated with nobility (the king’s official billiards maker, a cabinet maker, was the father of Jean Siméon Chardin),4On the relationship between Chardin and his father, as well as his early painting of the motif, see Lajer-Burcharth 2018. the game slowly reached the bourgeoisie during the eighteenth century, when it became more commonplace. In a painting shown at the Salon of 1808, Louis-Léopold Boilly used a game possibly played in the Oberkampf family’s castle of Montcel, in Jouy-en-Josas, in order to display a biting commentary on the sociability, the vices and the virtues of his time (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Louis-Léopold Boilly, Un jeu de billard, 1807, Saint-Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum.

It is a complex and rich image, where generational and gender relationships clash into one another. In her analysis of the painting, art historian Susan L. Siegfried lingers on the threatening aspect of the female player, seen from the back and eroticized, aiming for the balls – a sign of the new state of play between genders and one often used in popular imagery during the century. 5See S. L., Siegfried. Whereas the sport is linked with virile confrontation and spaces of masculinity, many images of the game feature female players and used it as an excuse to objectify them, and even, sometimes, to comment (from a masculine point of view) on the way the rules of seduction had changed; all of this at a time when European feminism was pushing forward.

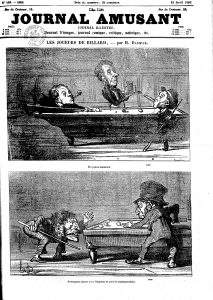

During the nineteenth century, when the popularity of carom billiards in France was growing at an astonishing rate (competitions between great champions, around 1900, would have throngs of spectators), 6See G., Ortalli. representing it would therefore allow for a cross section of urban or rural society. Honoré Daumier discerned the potential of the motif: in a cycle dedicated to the game and made of ten plates, the illustrator was interested in how bodies carry themselves, but also in class relationships. (fig. 3)

Fig. 3. Honoré Daumier, “Les joueurs de billard”, Le Journal amusant, n° 485, 15 April 1865.

Ridiculous amateurs who cannot wield the cue stick are frequently used to comical effect, and the game room is transformed into the backstage world of the theatre of urban life. Large-bellied adversaries are shown in postures of artificial distinction or arguing with others, sometimes even in exhilarating fight scenes, where cues, balls and stools are swung around a small café. By their testing of human organism, scenes representing billiards allow for a representation of the way the habitus can be embodied and realized in an activity, that is to say in a hexis bringing together physical embodiment and moral attitude.

The art of the game

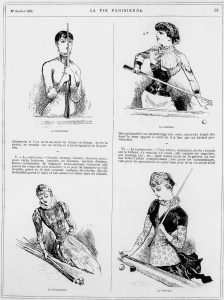

Beyond the social and moralizing discourse, beyond the setting up of “typologies”, even of historical “physiognomies” the nineteenth century was so fond of (fig. 4), the rise of billiards was followed by a multitude of treatises seeking to pierce its mysteries and its benefits. Mathematicians saw it as fertile ground to develop scholarly thought, whilst its most ardent proponents linked it to loftiest artistic practices. The analogy between billiards and fine arts seems to be, when one browses these texts, a natural shift.

Fig. 4. Yves and Barret, “Les joueuses de billard”, La Vie parisienne, 27 january 1883, p. 53.

Just as painting and sculpture, billiards can be practiced independently or within an academy. It necessitates wit, creativity, and calls upon skillful strokes that the practitioner’s body must uses a straight tool to make, and which he himself has to learn to master, as a painter with his brush. To an artist’s masterful use of the rules of perspectival construction, the billiard player can oppose a knowledge of angles and mathematics. Indeed, the game itself calls upon effects, lines and colors, serial production, and invokes a lexical field that can easily be used for images, their production or their rhetoric power. Finally, the table frame and its green cloth, when considered in all of their materiality, offer a reenactment of the bi-dimensional surface of the painting as an object.

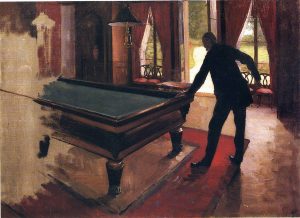

Edgar Degas, obsessed by the game and creator of two silent views of the empty billiard room in his friend Paul Valpinçon’s house in Normandy, is an example of this union between recreation and art. In his memoirs, Ambroise Vollard mentions the intense frustration Degas would feel when the usual players at his downstairs bar would fail to show up – as he so enjoyed drawing them. (fig. 5).7A., Vollard, Degas (1834-1917), Paris, Éditions Georges Crès et Cie,1924, pp. 109-110.

Fig. 5. Edgar Degas, sketch of a pool player, Sketchbook n° 3 (p. 15), Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Réserve 4-DC-327 (D,3).

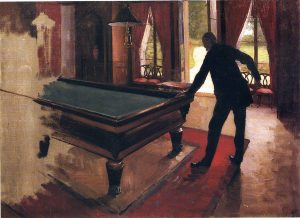

Just as ballerina’s bodies, observed in their many contortions, so did the bent bodies of billiards players over a table offer an interesting enough excuse to look his fill and awaken his sensitivity for mimicry, as told by Paul Valéry. Through its angles and geometry, as well as the visual gymnastics it demanded, the motif answered three of his interests: awkward postures, social behavior and strong lines. In a letter to his friend Albert Bartholomé, Degas even describes his dejection when faced with the clearly unruly motif.8Degas, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais (RMN), 1988, p. 506 : in a letter from Degas to Bartholomé, dated 1892, “ I wanted to paint and turned to billiard scenes. I thought I knew some perspective, but in truth I knew nothing of it, and believed you could replace it through applying various perpendicular and horizontal processes as well as measure angles in space through sheer will. I was tenacious” Gustave Caillebotte, another tenacious perspectivist attached to the nebula of impressionism, also surrendered and left his intimate backlit scene of his father playing carambole in this family home of Yerres unfinished (fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Gustave Caillebotte, Le Billard, 1875-76, private collection.

The revenge of the table

Shortly before 1900, billiard tables were ready to soar. Used and un-played in the Arles paintings of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, they were there to underline the torpor and symbolism in their scenes of cafes at nighttime. Draped in its green cloak, the horizontal object is radiant, slowly inching to the forefront of the painting before espousing its boundaries. Although it was little represented during the golden age of cubism, the billiard table was still the subject of a later series of sketches and no less than seven paintings by George Braque, around 1950. These images do not express the return of stability after the chaos of global conflict: rather, they unbalance the viewer by bringing together the vertical and the horizontal along an imaginary slanted line. His friend Francis Ponge, thinker of the idea of “planitude”, would be attuned to this. 9F., Ponge, La Table, Paris, Gallimard, 2002, p. 68 : “The Table is (also) the tipping from back to front (from behind a man to before him) of the wall, its positioning no longer vertical but horizontal (although truly, it is inclined : just like Braque’s billiard table is broken in its horizontality into a vertical oblique).” Netherlandish artist Jacqueline de Jong would also, in the middle of the 70’s, seize upon the possibilities created by skimming the surface of the object in a remarkable series dedicated to the game. It explored with equal depth formal puns – pushed to the very limit of the figurative – and playful discourse on human interaction.

Fig. 7. Sherrie Levine, La Fortune (after Man Ray), 1990, photo. by Richard Lemarchand

But it is the American artist Sherrie Levine, when she chose to recreate in three dimension the billiard table found in a work by Man Ray (fig. 7), that allowed the game its rebirth into the world. From reality to illusionist representation, and then from the later to abstraction, the table can therefore return into the realm of things, as if it were escaping the painting. This appropriative approach appears to justify Baxandall’s comments on art history as a situational game, and playfully challenges the discipline in its quest for balance between the purely visual and the social.

[1] M. Baxandall, Patterns of intention: on the historical explanation of pictures, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1985, p. 60.

[2] M. Baxandall, Patterns of intention, p. 60.[3] H. Damisch, ‘L’échiquier et la forme “tableau”’, in Lavin I. (ed.), World Art: Theme of Unity in Diversity, University Park, Pennsylvania, State University Press, vol. 1, 1989, pp. 187-191.

[4] On the relationship between Chardin and his father, as well as his early painting of the motif, see Lajer-Burcharth 2018.[5] See S. L., Siegfried.

[6] See G., Ortalli. [7] A., Vollard, Degas (1834-1917), Paris, Éditions Georges Crès et Cie,1924, pp. 109-110. [8] Degas, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais (RMN), 1988, p. 506 : in a letter from Degas to Bartholomé, dated 1892, “ I wanted to paint and turned to billiard scenes. I thought I knew some perspective, but in truth I knew nothing of it, and believed you could replace it through applying various perpendicular and horizontal processes as well as measure angles in space through sheer will. I was tenacious”. [9] F., Ponge, La Table, Paris, Gallimard, 2002, p. 68 : “The Table is (also) the tipping from back to front (from behind a man to before him) of the wall, its positioning no longer vertical but horizontal (although truly, it is inclined : just like Braque’s billiard table is broken in its horizontality into a vertical oblique).”Bibliography

Baxandall, M., Patterns of intention: on the historical explanation of pictures, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1985.

Golding, J., (ed.) Braque. The Late Works, exhibition catalogue, London, Royal Academy of Arts (Yale University Press), 1997.

Claass, V., ‘Degas Carambole’, Nouvelle revue française, no 629, March 2018, pp. 85-89.

Claass, V., Jeux de position. Sur quelques billards peints, Paris, Éditions de l’INHA, 2021.

Coriolis, G.-G., Théorie mathématique des effets du jeu de billard, Paris, 1832.

Damisch, H., ‘L’échiquier et la forme “tableau”’, in Lavin I. (ed.), World Art : Theme of Unity in Diversity, University Park, Pennsylvania, State University Press, vol. 1, 1989, pp. 187-191.

Degas, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais (RMN), 1988.

Hirschler, E., Le Billard au XIXe siècle et son influence sur les mœurs, Marseille, Imprimerie Saint-Ferréol, 1874.

Lajer-Burcharth, E., The Painter’s Touch. Boucher, Chardin, Fragonard, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2018.

Ortalli, G., ‘Vignaux and Slosson : 1880-1882. Billiards and Signs of New Departures in Ludicity’, Ludica, 15-16, 2009-2010, pp. 99-112.

Mingaud, F., Le noble jeu de billard. Coups extraordinaires et surprenans, qui ont fait l’admiration de la majeure partie des souverains de l’Europe, Paris, 1827.

Morehead, A., ‘Modernism and the Green Baize’, NonSite.org, no27, 11 February 2019.

Ponge, F., La Table, Paris, Gallimard, 2002.

Siegfried, S. L., The Art of Louis-Léopold Boilly. Modern Life in Napoleonic France, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1995.

Vollard, A., Degas (1834-1917), Paris, Éditions Georges Crès et Cie, 1924.

Victor Claass holds a PhD in art history and has been a research coordinator at the Institut national d’histoire de l’art since 2019. He teaches art history at various universities. His book, Jeux de position, on which the current text is based, will be published in autumn 2021 by the Éditions de INHA.