Armelle Fémelat, whose dissertation on Italian equestrian portraiture from the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries is forthcoming, brings us into the world of representations of animals shown dead or alive, wherein things have lives of their own. She invites us to grasp, through the world of forms, the nature of animal otherness by crossing the boundaries of time and space.

Animals and the Paintings of Things

Armelle Fémelat

From the standpoint of the problem of the representation of animals, the phrase painting of things proves more pertinent than the established term still life (nature morte, in French; literally, “dead nature”).1 More open, painting of things encompasses the innumerable representations that remain at the edges of academic genres. Represented dead or alive, animals constitute a particularly interesting prism for “accounting for the very life of things,” an approach advocated by Laurence Bertrand Dorléac. A major issue, the liberation of animals in their own lives as painted objects and subjects is nevertheless no easy thing. As Elisabeth de Fontenay recalls, it is always “at the horizon of our thoughts and tongues that animals stand, saturated with signs; it is at the boundary of our representations that animals live and move about, that they flee and gaze upon us.”2 It also seems desirable to rid ourselves of an overly anthropocentric viewpoint and gaze in order to apprehend animals, up to and including within the ways they are represented. Thus does Éric Baratay endeavor to grasp the living dimension of their history through their ways of living, reacting, and feeling, in interaction with the history of men.3 A translation toward the animal standpoint leads one to ask oneself what painted animals express about the artists who have represented them, about the society that has generated them, and indeed, perhaps, about themselves. Qua subjects, pictorial objects born of a creative approach reveal the entire diversity of the relationships they maintain with men; here, we are speaking of wild animals and domesticated ones, living ones as well as dead ones, whether at the hands of men or not. What is missing in France is a sensorial and material approach, which has already been undertaken across the Channel and transatlantically within the framework of Animal Studies and Cultural Studies, where it has the merit of offering novel methodologies that, in the most convincing cases, are capable of rounding out our knowledge of animals.

On the Boundaries of Reality

From its beginnings, the painting of things has, thanks to trompe l’oeil techniques, played with the boundaries of reality. Animals are featured in these pictures that create the illusion of a continuity between real space and a fictive space, often combined with furniture or architectural elements. A celebration of the painter’s virtuosity and of the mimetic power of painting, their resilience stems from the surprise that is generated at the moment when the viewer becomes aware that his perception has been manipulated. That is what is going on in Jacopo de’ Barbari’s famous Dead Partridge (1504, Munich, Alte Pinakothek), painted for the interior of a hunting lodge of Frederick the Wise, and in the no less celebrated Goldfinch by Carel Fabritius (1654, The Hague, Mauritshuis), originally nailed to a wall near the front door of the home of a friend of this Dutch painter, a homonym of the small feathered creature. The visual and pictorial significance of these two birds is coupled with a symbolic dimension and a discourse on the act of painting. A traditional motif in the genre of hunting trophies, the partridge evokes desire and pleasure, nay even lust and concupiscence, just as do the hare and the rabbit with which it is often associated. The symbolic dimension of such animals stems from the emblematic language that was then dominant and immediately decipherable by each and everyone. Traditionally identified as the first independent still life of the modern era, Barbari’s small panel has become a veritable topos of the genre, the pictura princeps in a long catalog of paintings. For its part, the goldfinch is counted among the domesticated animals people liked to teach to sing and fetch water. A symbol of resourcefulness on account of its agility and its alleged intelligence, but also a symbol of captive love and salvation of the soul, it is present in various genre scenes, particularly in seventeenth-century Dutch painting, notably in the works of Gerrit Dou and Abraham Mignon. Far from anecdotic, Fabritius’s enigmatic goldfinch, on the other hand, has not ceased to inspire viewers of yesterday and today.4 Represented life-sized and attached to the perch of its feeding dish, it displays its captive state as an animal subjugated by men, up to and including within the pictorial act itself.

1. Frans Snyders, Table avec deux chiens et un perroquet, 1641, huile sur toile, 141×210 cm, collection particulière.

Constant in the modern era’s painting of things, the combination of animal motifs and an illusionist inspiration sometimes condenses the trompe-l’oeil effect into a single compositional element. Often used is a fly, as in several paintings by Willem van Aelst (ill. 1), where the insect is the sole figure represented life-sized. A topos of Western painting,5 the trompe-l’oeil fly is just as much a demonstration of technical virtuosity and artistic value as it is an ambiguous symbol of death that makes reference both to the flight of the soul and to the rotting of the flesh. Despite its small size and the slight significance men grant it, the necrophagous fly is a decisive key to the reading of these pictures, a prototype of the iconic detail as theorized by Daniel Arasse.6 The living insect is visually set on the remains of game killed by man. This is a way of staging the very life of this untamable animal so likely to irritate humans against their will. The painting of things asserts itself also as the painting of the life instinct, of animal otherness, of the paradox of beauty and aesthetic delight, coming from a cruel and austere object of meditation.

Solicitation of the senses constitutes another bridge between reality and fiction. Constant in the painting of things, the appeal to the five senses is coupled, in the modern era, with a moralizing discourse that makes reference to moderation and one’s finitude. Themselves multisensory, animals, which are often the sole animated beings in representations, are as much evocations as they are sensorial invitations addressed to the viewer through his sight, which serves as a mediation.

The Play of Materials

2. Willem van Aelst, Trophée de chasse, ca 1665, huile sur toile, 65,5×52,7cm, collection privée.

Pelts, plumage, and scales but also elytra, carapaces, or shells—all these textures that call for pictorial virtuosity have not failed to inspire artists during the modern era. The Antwerpian specialist in animal painting after Frans Snyders (ill. 2), Jan Fyt (ill. 3) soon surpassed his master in the representation of furs and plumage, which ensured his fame, particularly in the domain of hunting trophies.7 Beyond their Baroque lyricism, his works drew their strength from the plasticity of their rendering of animal remains, particularly of wounds and spilled blood, though there is no general agreement about how these are to be interpreted. While some see therein mere objects of pictorial enjoyment echoing the pleasure of the hunt,8 others detect therein the moving expression of unease and of empathy that stem from the contrast between the search for visual pleasure and the violence breathed into the animal’s body.9

3. Jan Fyt, Volailles et fruits, années 1640-1650, huile sur toile, 112×145 cm, collection particulière.

Starting in the seventeenth century, a few artists in effect surged onto the perilous path of celebrating materiality itself and of highlighting the pictorial gesture. The matter of painting then came to reinforce the figuration of animals—and, particularly, dead animals. Exhibited in this way, painting that displays its depth and its density, begins, even though it may aggressively strain the eye, to resonate with the violence underlying the death of the animal whose remains are thus inflicted upon one’s gaze. A pioneer in this subject, Rembrandt marks a break with his Flayed Ox (1655, Paris, Louvre Museum), a mass of doughy matter that bears the stigmata of its kneading. The brutality of this neutered bull carcass which seems crucified, exhibited by man, stems as much from the subject matter as from the manner in which it is depicted.10 Thus imposed both materially and gesturally, as well as in respect to its problematic relations with the painter, the representation of certain animals adorns them with an unprecedented subjectivity. Has the artist adopted an ethical position? Is this an expression of animals about the nature of their relations with men, a denunciation of human savagery? That is how it is felt.

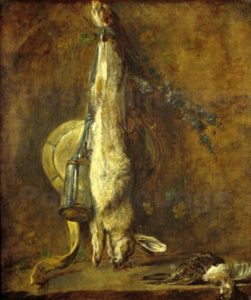

Stylistically less aggressive but just as radical in its approach, the work of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (ill. 4) pursues this reinvention of animal representation on the material level. If Chardin is to be believed, the artist would have been “converted” to still lifes after someone had offered him a dead rabbit, hoping that he would “render [it] with the greatest veracity in all respects and yet tastefully, and without any appearance of restraint that could render the execution dry and cold.”11 What emanates from the animals painted by Chardin is an odd impression of complicity as well as, in the cases of dead animals, a discreet yet constant feeling of pathos and sadness which became ever more perceptible as time went on.

4. Siméon Chardin, Lapin de garenne, grive et alouette, ca 1730, huile sur toile, 73x60cm, collection privée.

As in Fyt’s work, the blood stain stands out as a particularly significant detail, a pictorial detail and an emblem of representation, we would say in light of Arasse’s analysis.12 In a silent atmosphere open to contemplation, Chardin expresses, with tenderness and modesty yet without sentimentality, a certain dose of empathy toward these remains abandoned in death. Sarah Cohen has recently proposed interpreting these pictures as an invitation to the viewer to sympathize with the animals represented and to imagine oneself in their bodies. Though not totally convincing, this ecocritical interpretation is based on an anthropo-decentered interpretive strategy that is justified, according to this art historian, by the twofold acknowledgment that animal representations appeal to the senses and that animals have recently been recognized to possess a certain degree of subjectivity.13

Taking up again the brutality of Rembrandtesque painting, the dead animals of Francisco de Goya cross the threshold of modernity on account of their pathos. Their merciless material force opens up novel perspectives on the representation of animals. With Goya the visionary, the dead animal is posed and posited as an image of pain and disaster. Incredibly well composed, and with an extraordinary violence, his rare, late Bodegones show the violent and bloody death of animals just as much as they exhibit human cruelty and finitude, as in the image of the lamb’s head that appears as a sort of animal self-portrait (ca. 1808-1812, Louvre Museum). With Goya and, after him, Oskar Kokoschka, Chaim Soutine, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, animal painting becomes the reflection of a psychological state, a mirror and private theater for a new era.

Notes

1 This term has nevertheless been taken up again recently during the Von Schönheit und Tod: Tierstilleben von der Renaissance bis zur Moderne exhibition, which was held at the Staatliche Kunsthalle of Karlsruhe from November 19, 2011 to February19, 2012, and then at the “L’animal ou la nature morte à ses limites” colloquium co-organized by the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature (Museum of hunting and nature) and INHA (French National Institute of Art History), May 15 and 16, 2014.

2 Elisabeth de Fontenay, Le silence des bêtes. La philosophie à l’épreuve de l’animalité (Paris: Fayard, 1998, 2013), p. 19.

3 See, in particular, Eric Baratay, Le Point de vue animal. Une autre version de l’histoire (Paris: Seuil, 2012).

4 Including recently the American novelist Donna Tartt, with her The Goldfinch (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013). On this painting, see Frederik J. Duparc, ed., Carel Fabritius, 1622-1654, exhibition catalog (The Hague: Mauritshuis, 2004).

5 See, in particular, André Pigler, “La mouche peinte: un talisman,” Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux Arts (Budapest), 24 (1964): 47-64; André Chastel, Musca depicta (Milan: F.M. Ricci, 1984).

6 Daniel Arasse, Le détail, Pour une histoire rapprochée de la peinture (Paris: Flammarion, 1992, 1996), pp. 117-26, and his Histoires de peintures (Paris: Éditions Denoël, 2004; Paris: Gallimard, 2007), pp. 286-87.

7 Raphaël Abrille, “Trophées de chasse peints en France aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles,” lecture delivered May 15, 2014 during the L’animal ou la nature morte à ses limites colloquium at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, from the article that appeared in the catalog of 2011 Karlsruhe exhibition. We thank the author here for having transmitted to us this text.

8 Olivier le Bihan, Trophées de chasse, exhibition catalog (Bordeaux: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, 1991), p. 24.

9 Thomas Balfe, “Fake Fur: The Animal Body between Pleasure and Violence,” lecture delivered May 16, 2014 during the L’animal ou la nature morte à ses limites colloquium at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature.

10 Gérard Dessons, Rembrandt, l’odeur de la peinture (Paris: Éditions Laurence Teper, 2006), passim.

11 Charles Nicolas Cochin, Essai sur la vie de Chardin (1780), published by Charles de Beaurepaire, Précis analytique des travaux de l’Académie des Sciences, Belles-Lettres et Arts de Rouen (1875-76), vol. XXVIII, p. 421.

12 Daniel Arasse, Le détail, Pour une histoire rapprochée de la peinture (Paris: Flammarion, 1992, 1996), pp. 7 and 194-95.

13 Sarah Cohen, “Ecocriticism as a Critical Strategy Applied to Animal Still Lives: Chardin,” lecture delivered May 16, 2014 during the L’animal ou la nature morte à ses limites colloquium at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature; a book on this subject is forthcoming.

ARASSE, Daniel. Le détail. Pour une histoire rapprochée de la peinture. Paris: Flammarion, 1992, 1996.

Beauté animale. Exhibition catalog. Paris: RMN-Grand Palais, 2012.

BOYSSON, Bernadette de and Olivier LE BIHAN. Trophées de chasse. Exhibition catalog. Périgueux: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, 1991.

EBERT-SCHIFFERRER, Sibylle. Natures mortes. Paris: Citadelles & Mazenod, 1999.

JACOOB-FRIESEN, Holger. Von Schönheit und Tod. Tierstilleben von der Renaissance bis zur Moderne. Exhibition catalog. Karlsruhe: Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, 2011.

JOLLET, Étienne. La Nature morte ou La place des choses. L’objet et son lieu dans l’art occidental. Paris: Hazan, 2007.

KOSLOW, Susan. Frans Snyders, peintre animalier et de natures mortes (1579-1657). Antwerp: Fonds Mercator Paribas, 1995.

STERLING, Charles. La Nature morte. De l’Antiquité au XXe siècle. Paris: Macula, 1985.

ZUFFI, Stefano. Ed. La Nature morte. Paris: Gallimard, 2000.