In 1980, the title of a key exhibition held at the French National Museum of Modern Art–Realisms: Between Revolution and Reaction, 1919-1930--announced a program. The project manager for this show, Gérard Régnier (Jean Clair), recalled our common-sense understanding of the term Realism: “the artist’s scrupulous observation of the model being represented, whether it be a figure, a face, or a still life and even if the study in question results in a composition that is allegorical or religious in nature.” The plural emphasized, rather, diversity, and here, the curator was taking up the arguments of the pioneer in the field, Jean Laude, whose writings back then had been forecasting all the right questions for more than twenty years. As early as 1919, Laude said at the time, “a kind of discourse was being worked out and built up across Europe [as we shall see, it would be fitting to add there the United States] whose intention was to put an end to past errors–against which, moreover, it warned. In literature just as much as in music, it rehabilitated national cultural values, a taste for work well done, good craftsmanship, and tradition.”

Laude recognized the weight of the historical context that influenced works of art. And even if today we know that the much-talked-about return (or call) to order was already underway prior to the onset of the first world war, what seized hold of Western societies thereafter was a sense of melancholy if not feelings of nausea, along with fear of decline and of a renewal of violence as well as destructive impulses. In art as elsewhere, the retreat into nationalism was the symptom of an identity crisis taking place just as culture with a capital “C” was being used as the last rampart. What happened next revealed the historical ineffectiveness of such an approach. Along the way, what appeared was a series of borrowings and citations from Realist models as well as détournements thereof that in no way strayed from the “modern” path–at least from a part of it–and thus this movement extended far beyond the scope of some of its reactionary participants.

François Legrand retraces the key episodes that have occurred on the America scene since the nineteenth century, when a definition of the criteria for Americanness was worked out in the United States and when a coherent past was invented for artistic Realism so that it might rival modernism and cosmopolitanism. For his part, Jérôme Bazin studies the particular circumstances of Socialist Realism in the postwar German Democratic Republic, where people in their social capacities became the main subject for a kind of painting that was designed above all to educate the masses but that played out in ways that were less conventional than originally foreseen.

The fact that, in both cases, Realisms would be called upon to support such varying causes proves not only the model’s elasticity but its ambiguous force at the very moment one wished to make art play an eminent social role.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

François LegrandLife without the Work,

or the Invention of Thomas Eakins:

Isolationism and Realism

Ill. 1. Thomas Cole, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm–The Oxbow, 1836, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“The Americans,” wrote the critic Royal Cortissoz in 1925, “need to know the soil in which their evolving art is rooted.” Establishment of nineteenth-century American Realism’s reputation is not unrelated to the climate of isolationism that was to leave its mark on the United States after the onset of the Great Depression. On the cultural level, such withdrawal favored an exclusive celebration of America as one’s artistic compost and allowed this desire for artistic independence to be expressed in the promotion of Realism. The words uttered a generation earlier by the painter William Merritt Chase–viz., “I would rather go to Europe than to go to Heaven”–would no longer have fit any place. Indeed, such an attack on one’s “spiritual homeland” had become outdated.

In order to get a true grasp on the remonstrative character of these positions during the interwar period, it is fitting to go back over a humiliating memory in American art history. From the early nineteenth century onward, American art felt that, with landscape painting, it had hold of its characteristic art form.

Ill. 2. Fritz Hugh Lane, Owl’s Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine, 1862, Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Identity-based art had even helped the country put an end to the strong disapproval of art found in the Puritan ethic. Art and religion could thenceforth converge in Nature. And yet this nature was quite singular, for it remained associated with a messianic plan that conferred upon landscape the grandeur usually associated with historical painting. If what the American territory offered painters was a divine mirror, what painters held up to the nation was an ideal image of itself taken to be a genuine self-portrait. (Illustrations 1 and 2)

This motif of national pride was going to collapse, however, in the wake of sarcastic remarks put forth by Parisian critics during the Universal Exhibition of 1867. Their violent rejection of American landscape painting undermined the confidence of the American art world and put it back into a position of apprenticeship and dependency vis-a-vis Europe.

The “Spiritual Homeland” Versus Cosmopolitanism

The interwar period, on the contrary, was a time of consolidation for America’s national identity. Some critics were to make it one of their missions to define “objective” criteria of Americanness. The past becoming the condition for the future, to invent for oneself an artistic past was also to stand out in contrast to present-day art and to maintain the supremacy of the figurative, the real, and the local over against the basic premises of modernism. Quite logically, the resentment certain critics felt toward any form of cosmopolitanism could even end up undermining the prestige such honored figures of the previous generation as James Whistler and John Singer Sargent had enjoyed.

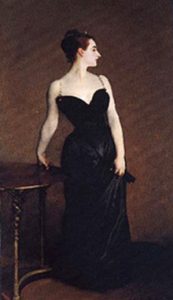

Ill. 3. John Singer Sargent, Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau), 1883-1884, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Christine Savinel has highlighted a coincidence brought out by Whistler’s detractors–that between the “wavering identity” of his image as an artist (moving as it did between Europe and the United States) and the pictorial “blurriness” of his work. Whistler was accused of establishing the reign of “no-place.” An apostle of art for art’s sake, Whistler made of art “his own place,” thereby rendering impossible any kind of national enrollment. As for the cosmopolitan celebrity of a Sargent, it rested upon the success of his “transnational” painting of society figures. In the name of an ideology of the highly finished product and of a social morality of work well done, some compared the painter’s “fa presto” style to a licentious and immoral form of deviancy (illustration 3) and his aristocratic bent to a European sort of impropriety. Cosmopolitanism, as we know, has always had a whiff of decadence about it.

During the 1930s, some supporters of Regionalism–the meticulous figurative art of rural America–were going to harden their views on the country’s cultural heritage and thereby rediscover, in the art of the past, the “faithful reflection of the American spirit.” One of the most chauvinistic defenders of this “specific” and “particular” American-style art, Thomas Craven, was to radicalize the paradigm of manliness maintained by the upholders of Realism. The “effeminate” would thenceforth be the synonym for the “foreign,” and abstraction, an imported kind of art, would be viewed as inevitably devoted to artifice–as opposed to Realism, an authentic “local product”–and “impotence.” From this perspective, Realism would signal the return “to masculine virtues, for,” wrote Craven, “all the great painters are rude, gruff, and insufferable.

In this logic of restoration, an instrumentalization of the past was going to allow a new genealogy of the “American School” to be worked out, one protected from any trace of corrupting European influences. And yet, before one could rehabilitate these American “heroes,” one still had to “invent” them.

Goodrich and the Invention of Eakins

Ill. 4. Entourage of Thomas Eakins, Thomas Eakins at about Age Thirty Five, 1880, print on albumenized paper, Bryn Mawr College Library.

The art historian Lloyd Goodrich (1897-1987), who pursued his career at the Whitney Museum of American Art, was one of Eakins’s principal proponents from the early 1930s onward. In order to find the antidote to cosmopolitan blurriness, one had to invent the anti-Sargent–in other words, a foundational and compensatory figure, someone who was “American to the Core,” a “solitary oarsman” who would answer to the imperatives set out by the new cultural values: taking a solitary path, showing an absence of sophistication, and engaging in unaffected formal innovation. In some respects, one would be tempted to conjure up here a nineteenth-century version of Jackson Pollock. . . .

Goodrich’s monograph, Thomas Eakins, His Life and Work, which was published in 1933 by the Whitney, resuscitated as much as it created this rustic image of a precursor renowned for “misunderstanding, persecution, and neglect.” The Eakins myth was thenceforth a part of the history of art.The psychological construction of Eakins the “pioneer” contrasts point by point with the society archetypes to which Sargent gave bodily form and demonstrates to what extent the aesthetic values advanced by his admirers pertained above all to the realm of moral precepts. His legendarily sloppy way of dressing (illustration 4) thus became a metaphor for his pragmatic grounding in everyday experience. Such anticonformism, which lacked any working-class connotations (Eakins firmly belonged to Philadelphia’s middle class), distanced him as much from the Romantic model of inspiration (illustration 5) as it did from either the artistic Bohemianism or the desire for social self-promotion seen in painted portraits and photographic images of Sargent’s and Chase’s studios (illustration 6). In order to highlight this contrast with the “superficial” and casual art of his two fellow painters, Eakins was going to be erected into the very model of virility, plainspokenness, meticulousness, objectivity, and obstinate independence.

Ill. 5. Anonymous. Thomas Moran in His Studio with Mary, 1876, New York, East Hampton Library.

Such praise for Eakins the man allows one to grasp the scope of the comparative reversal the image of the American artist had undergone. Between the late nineteenth century and the interwar period, Eakins’s breaches of etiquette in a still Victorian art world were gradually going to be highlighted more and more as clear signs of artistic accomplishment.

Eakins’s dismissal from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1866 for indecency–he had had his students pose nude (illustration 7)–was to become the cornerstone for his retrospective aura as a “rejected” artist. Even though hostility toward this man who was martyred for his adherence to the “real” truth owes nothing to fiction, the use overzealous biographers would make of his setbacks was systematically aimed at building up a mythical model of the American artist. In the context of 1930s’ isolationism, the image of Eakins as self-made man triumphing alone over a series of trials had the great advantage of setting him in contrast to the model of the European artist, who was perceived as a mere inheritor and therefore incapable of originality. So much was this the case that Goodrich, along with Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, strove to minimize and even to deny the artistic impact of this American artist’s Paris sojourn in the studio of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1866-1869).

Ill. 6. John Singer Sargent, William Merritt Chase, 1902, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Integrity of Realism

Within this ideological context, the objectivity of Realism was to be understood as a guarantee of moral integrity as well as testimony to national fidelity and loyalty toward the “sacredness of everyday fact.” The art of Eakins was said to have gotten back in touch with the Puritan wish to have an “art without style,” a “style without style.” (Clement Greenberg himself described Eakins as a “mannerless artist” whose style was “neutral and transparent.”) Here, the absence of style becomes a moral condition. For, style without style, art without seduction, reconnects with the phantasm of an innocence and purity that would wash art clean of any suspicion of immorality or uselessness. An art without style is also an art that is immediately legible and intelligible. Such an alleged immediacy in the language of Realism harks back to the old dream of a kind of art that would be adequate to its model: without any gap, beyond all convention, free from all foreign corruption, and not bound by any prior traditions. For Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the art of Eakins, cut off from its French influences, symbolized “American Puritanism and its intolerance of evil.” The old fascination with the (often fictive) model of the self-taught Realist artist (George Caleb Bingham, Winslow Homer) also goes to reveal this obsession with rediscovering the lost paradise of transparency. Spontaneously generated, such honest and upstanding Realism was said to spring up on its own from the American soil–like sansevieria, the potted plant known for its capacity for resistance that Grant Wood’s old-fashioned mother bore like an emblem in a 1929 portrait. The sturdiness of the land engenders authentic American art, that of the “pioneers.”

Ill. 7. Entourage of Thomas Eakins, Thomas Eakins Carrying a Nude Woman at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 1883-1885, digital inkjet print from the dry gelatin plate negative, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

Ill. 8. Thomas Eakins, The Portrait of Professor Henry A. Rowland, 1897, Addison Gallery of Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts.

The Willful Blindness of Critics

This heroic construction of the figure of Eakins was based upon a clear misunderstanding of the reflective and conflictual nature of his art. How could it have been otherwise when Goodrich and his close associates reduced Eakins’s contribution to mere thematic and documentary observations about American life? In Eakins, the themes presented–rowing, boxing, surgery–and the practices highlighted–anatomy and perspective–were never but tools employed in the service of dissident pictorial procedures.

At the antipodes of the kind of Realism that would offer but a reassuring report on how things really are, Eakins converted his experience of reality into visual drama. Eakins’s art, based as it was upon enigma, conflict, and violence, was constantly opposed to the notions of objective evidence and direct observation later highlighted by Goodrich. The graffiti-covered frame from The Portrait of Professor Henry A. Rowland (illustration 8) brutally contrasted two irreconcilable levels of reality: painting and writing, that “accident affecting the purity of language” (Derrida).

Ill. 9. Thomas Eakins, John Biglin in a Single Scull, 1873-1874, New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery.

Ill. 10. Thomas Eakins, The Gross Clinic, 1875. (This canvas was recently put up for sale by Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College. A fund-raising effort has been launched by various Philadelphia cultural institutions in order to keep it within the city.)

In his rowing scenes (illustration 9), which are lacking in all spontaneity, the unprecedented emphasis placed upon reflections in the water and the figure’s dissolution therein is from the start but a metaphor for the reflective nature of his art. Pushing Realism to its extremes, Eakins made of reflection an almost frightening instance of disfigurement. In The Gross Clinic (illustration 10), which caused a scandal for being “violent and bloody,” Eakins shows that the violent nature of the theme–a diaphysectomy performed before an audience in which Eakins himself can be recognized–is never but that of the painter toward the viewer. Everything points toward an iconoclastic relationship to the human body: the illegible body of the patient seems to have its very integrity attacked, while the scalpel, red with blood, sets the patient’s mother to cringing as she covers her face. Michael Fried has now offered an up-to-date account of this dialectic of repulsion and fascination: a refusal to look accompanied by a sadistic impulse to frighten. “The definitive realist painting,” he states, “would be the one that the viewer literally could not bear to look at.”

“For the public I believe my life is all in my work,” wrote Eakins in 1894. The ideological mistake made by Goodrich and the advocates of this identity-based reappropriation of Eakins in the 1920s and 1930s was to blind themselves, like the patient’s mother who turns her gaze–doing so to the point of believing that “his work was all in his life.”.

Bibliography

Americans in Paris, 1860-1900. Ed. Kathleen Adler, Erica E. Hirshler, and H. Barbara Weinberg. Contributions from David Park Curry, Rodolphe Rapetti and Christopher Riopelle. With the assistance of Megan Holloway Fort and Kathleen Mrachek. London: National Gallery, 2006.

Chassey, Eric de. La Peinture efficace. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2001. (On Thomas Craven, see, in particular, pp. 86-89.)

Foster, Kathleen A. Thomas Eakins Rediscovered. Charles Bregler’s Thomas Eakins Collections at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997.

Fried, Michael. Realism, Writing, Disfiguration: On Thomas Eakins and Stephen Crane. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Lucie-Smith, Edward. American Realism. New York: Abrams, 1994.

Made in USA L’Art américain, 1908-1947. Ed. Eric de Chassey. Bordeaux, Rennes, and Montpellier: Éditions Réunion des musées nationaux, 2001.

Paris 1900. Les Artistes américains à l’Exposition universelle. Exhibition at Paris’s Carnavalet Museum. Paris: Paris musées, 2001.

Régnier, Gérard. Les Réalismes, 1919-1939. Paris: Éditions Centre Georges Pompidou, 1981.

Savinel, Christine. “Le cosmopolitisme de Whistler, Sargent, Wharton et James: une relation critique.” In L’art américain. Identités d’une nation. Paris: Terra Foundation for American Art, Louvre and École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 2005.

Thomas Eakins. With essays by Kathleen A. Foster et al. Chronology by Kathleen Brown. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2001.

Thomas Eakins: Painting and Masculinity/Thomas Eakins. Peinture et masculinité. Ed. Stéphane Guégan and Veerle Thielemans. Acts of a colloquium organized by the Orsay Museum and the Terra Museum of American Art. Chicago and Giverny: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2003.

Winslow Homer: Poet of the Sea/Winslow Homer. Poète des flots. Ed. Sophie Lévy. Chicago and Giverny: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2006.

François Legrand studied at the Louvre School and received a doctorate in art history after defending his thesis on Le Paradis perdu et l’esthétique romantique (The lost paradise and the Romantic aesthetic, 1996). He is the author of a book of interviews with Michel Laclotte, Histoires de Musées, Souvenirs d’un conservateur (2003). Legrand has collaborated with the Macula and Gérard Montfort publishing houses and now works with the monthly magazine Connaissance des Arts.