“I didn’t paint war scenes in order to prevent war; never would I have had that pretension,” Otto Dix told Otto Wundshammer in 1946. “I painted them in order to conjure war away. All art is conjuration.”

In evaluating his own work more than twenty years after the Great War of 1914-1918, Dix subscribed to what Pablo Picasso had foretold about art in the early years of the twentieth century: its impotence in changing the courses of things as well as its power of conjuration for artists engaged in the task of taking stock of the world as it is.

In the case in point, not having been able to account for the events as they were unfolding, his contemporaries, in refusing to reexamine them after 1918, opened another front for him and led him to handle another form of violence. Dix speaks there of the chaos that remains silent in the wake of Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, the Rhenish masters, and Francisco Goya’s The Disasters of War. All of those artists had the power to imagine the worst, and this was all the more the case for Dix, who had seen it with his own eyes in the trenches.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Frédérique Goerig-HergottOtto Dix:

Painting to Exorcize War

The artistic development of Otto Dix (1891-1969) was marked by his attachment to traditional painting, especially the tradition of German Renaissance painting, and by his discovery of the Symbolists, the Impressionists, the Cubists, the Futurists, and the Expressionists. Yet, more than the various artistic trends that nurtured his early years, it was his direct experience of war that would be decisive for his work and his career.

Enlistment in World War I

The Futurists presented war as a salutary experience,[1] and this idea was broadly shared in German Expressionist circles.[2] It was within this climate of euphoria that Dix enlisted as an army volunteer in 1914. Like most of his contemporaries, Dix hailed the war as symbolic of a new beginning and as the opportunity to leave behind a bygone, bourgeois era. He left for the front with his principal reference works—the Bible and Friedrich Nietzsche’s The Gay Science [3] —in hand, and he depicted his own enthusiasm in self-portraits.

From 1915 to 1918, Dix chronicled events on his postcards, in his drawings, and within his diary. Neither a glorifier of war nor a pacifist, Dix thought of war as a natural phenomenon and looked upon it in an objective manner. He freed himself from tension and fear by describing unstintingly his impressions of the front and the horrors one lives through there, seeking to experience the reality of war as closely as possible while expressing the fascination the experience of being under fire as well as the transformation of the terrain exerted upon him.

Painting to Exorcize War

Like others who were able to survive the conflict, Dix returned home haunted by visions of chaos. Encouraged by the Dadaist circle of Berlin as well as by his friend George Grosz, he painted at first in cynical fashion a vision of crippled humanity: war veterans who had been physically wounded (The War Cripples, Prager Straße, The Skat Players, 1920) and reduced to beggary (The Match Seller, 1920), offering thereby a contemporary echo to Jacques Callot’s works Miseries of War and Beggars, to which he made reference.

For Dix, as well as for the German artists of the realist and satirical Neue Sachlichkeit movement which he joined, it was a matter of looking at man in his downfall without idealizing him. Nurtured by his own recollections, his war drawings, publications by various veterans (Henri Barbusse, Ernst Jünger),[4] and photographic documents being circulated in the press, he brought out the dramatic consequences of human folly. The imposing picture The Trench, completed in 1923, shows with cold detachment a landscape annihilated by a hail of bullets and bombs and sprinkled with cadavers, bits of wood, twisted bars of steel, and barbed wire. Far from constituting any sort of pacifist argument, this raw and objective report on the outcome of battle mixes in with the horror of the subject itself a fascinating effect that is due to the refined use of a glazing technique he had borrowed from the old masters.[5] Compared to the work of Matthias Grünewald on account of the realism and brutality of its representation of violence and death, this picture references The Temptation of St Anthony panel from the Isenheim Altarpiece, a representation of struggle and destruction in which the saint, like the soldier, is delivered over to the omnipotent forces of evil.[6]

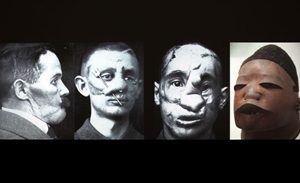

In 1924, Dix completed his cycle of engravings entitled The War, which expressed the absurdity of battle as a consequence of human instinct. Its themes of human suffering, death, atrociously mutilated bodies, and the devastation of nature stand here at the center of his discursive presentation. This cycle references, sometimes in direct fashion, that of Francisco Goya’s The Disasters of War. Yet Dix, inspired by mummified corpses from the Catacombs of Palermo,[7] images appearing in the press, photographs done by his friend Hugo Erfurth, and Ernst Friedrich’s album War Against War (1924), went further than the Spanish master in representing anatomical details and the various stages of bodily decomposition.

The use of etching techniques allowed him, moreover, to give to his representations an additional visual intensity, to illuminate details, to express the processes of putrefaction with subtle nuances, and to relive the stages of destruction contained in images of mutilated bodies.

Associated with pacifist movements and read as a denunciation of war, this cycle was rather, for the artist himself, more a means of exorcizing war by showing its effects.

The War Triptych (1929-1932)

In the late 1920s, Dix remained haunted by the traumatic experience of the first world conflict. With his imposing triptych The War, he dedicated a secular interpretation of the Isenheim Altarpiece to the memory of this conflict.

Substituting the horror of war for the horror of the Crucifixion, Dix gave to German art history a matching counterpart that is now as famous as the altarpiece painted by Grünewald, though in this case based not on the Passion of Christ but on the sacrifice and ordeal of soldiers at war. For Dix, recourse to Grünewald’s vocabulary, to his artistic technique (tempera on wood), and to the altarpiece format was a way to describe the reality of war by lading it with a sacred form of horror. The four panels that make up Dix’s work describe in biblical dimensions, but also in a cyclical Nietzschean worldview, the daily life of a soldier at war, going from nocturnal rest in the trenches and the next morning’s departure for the front to the survivors’ return from the conflict.

The central panel acts as a metaphor for the Crucifixion. What we are shown is really a devastated Golgotha instead of a field of battle.

Whereas, in Grünewald’s work, the finger of Saint John the Baptist is pointing toward Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross and the redemption it makes possible, the finger of the dead, impaled man hovering above the sinister, smashed-up landscape in Dix’s work points at the sacrifice of soldiers at war and, more precisely, at the corpse riddled with bullets, crucified upside down. At the bottom left, the torn-off head of a soldier, surrounded by a crown of barbed wire, is also evocative of Christ. Likewise, the scene on the right panel, where Dix represents himself going to the aid of a wounded man, harks back to the theme of the Passion, the Descent from the Cross, and the Redemption.[8]

Presented only once, in 1932, during the Fall exhibition at the Berlin Academy, the War triptych was stored away in a place safe from Nazi censorship until the end of World War II.[9]

Internal Migration (1933-1944)

Dismissed in Spring 1933 from his professorial post at the Dresden Academy he had occupied since 1927,[10] considered a “degenerate artist,” and banned in 1934 from exhibiting his works,[11] Dix, unlike other Verist painters, did not leave Germany. He settled on the banks of Lake Constance, painting only landscapes, biblical subjects, and portraits, areas in which he could still express himself without hindrance, though it did oblige him to turn his back on representing reality objectively. Often allegorical in character, some of his paintings ill concealed his anxieties, and the subject of the temptations or the hermitage of Saint Anthony lent itself to the use of metaphors for the harassment and exile suffered by the artist. Memories of the horrors lived during the war nevertheless rose up one last time in the picture Flanders (1936), which Dix dedicated to Barbusse (who had died in 1935). Inspired by the final chapter in Barbusse’s famous novel Under Fire, this painting, unlike all earlier works dealing with this subject, bore here the full weight of his sense of fatigue and resignation. Isolated at the time in his “internal exile,” Dix seems in a way, with this picture, to be taking a rest from the arrogant and exuberant vital outbursts that had characterized his early years. When the war broke out, his subjects spread out upon apocalyptic landscapes: in Lot and His Daughters (1939), for instance, his premonitory vision of Dresden in flames replaced Sodom and gave expression to his anxieties.

Otto Dix, Prisoner-of-War Painter in Colmar (1945-1946)

Enroled at age 53 in the Volkssturm,[12] Dix departed for the Western front (on the banks of the Rhine) in March 1945. Arrested in April in the Black Forest, he was interned at the prison camp in the Logelbach neighborhood of Colmar. After being recognized by the camp’s French commander, he was integrated into a group of artists and authorized to paint first in the studio of the Colmar artist Robert Gall (1904-1974) and then in individuals’ homes.[13] Enjoying a privileged status until his liberation in February 1946, Dix was to accept various commissions for portraits, landscapes, and biblical subjects, such as the major triptych of the Madonna of the Barbed Wire for the camp’s Catholic chapel.[14] In the central panel, Dix revived the Marian theme of the Rhenish Primitives—in particular, Martin Schongauer’s Madonna of the Rose Bower (1473), preserved in Colmar[15] —by setting the Virgin within the tragic context of the prison camp. Here, barbed wire has replaced the roses in front of a landscape in ruins that includes, in the background, the church of Logelbach and the Vosges. On the side panels, the representation of episodes in the liberation of Saint Peter and Saint Paul is meant to sustain the hope of upcoming freedom for the prisoners. In the picture Christ Healing a Blind Man, Dix represents himself in the guise of a disabled person (this is his sole known self-portrait from that period). Through this image, he evokes, all at once, humiliation, the absurdity of the prisoners’ situation, and the hope of a return to enlightenment and reason.

Among the numerous portraits executed by Dix in Colmar, one of them bears witness to the distressing living conditions of the camp’s detainees and prefigures his works to come. Within scenery from the Colmar camp, The Portrait of a Prisoner of War represents the painter Otto Luick (1905-1984), a member of the Stuttgarter Sezession, with his emaciated face, his lost look, and his half-open mouth. Luick’s resigned attitude, comparable to that of the crucified Christ from the Isenheim Altarpiece, and the barbed wire surrounding his head like a crown of thorns invite a comparison between the sacrifice of the soldier at war and that of Christ on the Cross.[16]

Dix’s Return to Germany, 1946

Upon his return to Hemmenhofen, Dix freed himself from the grip of World War II, as he had done after World War I, through his works, as he continued his internal migration at the margins of the new trends in German art. While life resumed in the midst of ruins in his pictures relating to war, the subject of the prisoner of war, whether hidden beneath the features of Christ or not, returned as a leitmotiv in his work. The themes of the Passion, the Mocking, and the Flagellation of Christ by Nazi torturers clearly denounce human folly and the horror of the Holocaust. While, in 1946, Zvi Kolitz was publishing on another continent the highly moving story of Yosl Rakover—a contemporary Job whose ultimate act of resistance is to bear witness[17] —Dix, upon return from captivity, painted his own representation of the biblical character Job. Referring directly to the character, covered with wounds, from Grünewald’s Temptation of Saint Anthony panel with which the patients at the Isenheim monastery could identify, Dix showed the episode in which Job, covered with sores after having lost everything, moves back, annihilated and humiliated, into the ashes of his ruined home. As a symbol of a devastated Germany and an icon of universal suffering and faith, the character of Job allowed an entire generation of traumatized people to identify with him.

In this picture as well as in the works executed after World War II, Dix, far removed from the cold descriptions he had offered in his youth, bore witness to, and solemnly transmitted to his contemporaries and to generations to come, the idea of individual responsibility as well as a faith in justice and dignity.

Notes

[1] The 1913 “Italian Futurists at the Der Sturm Gallery” exhibition in Berlin.

[2] The 1914 “New Painting: Expressionist Exhibition” at the Arnold Gallery in Dresden.

[3] As was the case for his contemporaries (Thomas Mann, Ernst Jünger, Arnold Zweig, etc.), Nietzsche was his principal philosophical reference.

[4] Barbusse’s work, Under Fire, which first appeared in French in 1916, won the Goncourt Prize that same year. The book was published in German (as Das Feuer) in 1918. Jünger recounted his experience in the trenches in Storm of Steel (In Stahlgewittern) in 1920.

[5] Exhibited at the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne, which had acquired the work, and then in Berlin, this picture created a scandal. Considered an insult to dead veterans, the picture, which has disappeared, had to be returned to Dix’s art dealer, and the museums director was forced to resign.

[6] Transferred from the Unterlinden Museum of Colmar to the Alte Pinakothek of Munich for the years 1917 to 1919, the Isenheim Altarpiece became, on account of its representations of the sufferings of Christ and Saint Anthony, an object of identification for an entire generation of Germans traumatized by the conflict.

[7] Dix had gone to Palermo during the Winter of 1923-1924.

[8] This dimension and this biblical motif are also to be found in Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927), with its martyrdom scene of the worker dying of fatigue, his arms forming a cross on the hands of the dial of his machine, to whose rescue Freder had just come.

[9] Sheltered by the collector and industrialist Fritz Bienert, it was later lent by Dix to the Gemälde Gallery in Dresden and finally acquired in 1963 by the Minister of Culture of the German Democratic Republic.

[10] He then painted The Seven Deadly Sins, an allegory for the threat to artistic freedom.

[11] He painted The Triumph of Death in reaction to this censorship.

[12] Name give to the German people’s militia levied in 1944 to provide backup for the Wehrmacht in defense of the Reich’s territory at the end of World War II.

[13] More than seventy worked executed in Colmar have recently been inventoried (see Goerig-Hergott, Colmar, 2012)

[14] Exhibited since 1987 in the Maria Frieden Church of Mariendorf (Berlin).

[15] At the Dominican Church in Colmar.

[16] September 15, 1945 letter. The Isenheim Altarpiece was again back in Colmar starting July 8, 1945.

[17] “Yosl Rakover Talks to God,” Yiddishe Zeitung, Buenos Aires, September 25, 1946.

Bibliography

DIX, Otto. Der Krieg. Berlin: Verlag Karl Nierendorf, 1924.

DIX, Otto. Lettres et dessins. Presented and translated from the German by Catherine Teissier. Cabris: Éditons Sulliver, 2010.

GOERIG-HERGOTT, Frédérique. “Les œuvres réalisées par le peintre allemand Otto Dix prisonnier de guerre à Colmar.” Annuaire de la Société d’Histoire et d’Archéologie de Colmar 2011-2012. Colmar, 2012: 227-61.

LECOQ-RAMOND, Sylvie. “Otto Dix: La Madone aux barbelés, une œuvre de captivité.” Regards contemporains sur Grünewald. Colmar: Musée Unterlinden and Paris: A. Biro, 1995: 62-89.

LÖFFLER, Fritz. Otto Dix, 1891-1969: Œuvre der Gemälde. Recklinghausen: Aurel Bongers, 1981.

RÜDIGER, Ulrike. Grüsse aus dem Krieg: Die Feldpostkarten der Otto Dix Sammlung in der Kunstgalerie Gera. Gera, 1991.

SCHWARTZ, Birgit. “Kunsthistoriker sagen Grünewald… Dans Altdeutsche bei Otto Dix in den zawanziger Jahren.” Jahrbuch der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen in Baden-Wurttemberg, 28 (1991): 143-63.

WILLE, Hans. “Der Colmarer Altar von Otto Dix.” Festschrift zum 65. Geburtsfag von Siegfried Salzmann. Bremen: Kunstverein in Bremen, 1993: 53-75.

Exhibition Catalogues

Otto Dix–Dessins de guerre 1915-1917. Galerie Tendances (Paris). December 1, 1988-February 18, 1989.

Otto Dix et les maîtres anciens. Unterlinden Museum (Colmar). September 7-December 1, 1996.

Otto Dix–Dessins d’une guerre à l’autre. French National Museum of Modern Art (Paris). January 15-March 31, 2003.

Otto Dix–Dessins de guerre 1915-1917. Galerie Tendances (Paris). April 1-June 24, 2006.

Otto Dix retrospektiv zum 120. Geburtstag: Gemälde und Arbeiten auf Papier. Kunstsammlung Gera. December 3, 2011-March 18, 2012.

Das Auge der Welt: Otto Dix und die Neue Sachlichkeit. Kunstmuseum Stuttgart. November 10, 2012–April 7, 2013.

Frédérique Goerig-Hergott is the curator of the modern and contemporary art collections of the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar. Her research and publications deal with works executed by Otto Dix during his incarceration in Colmar and with the effect the Isenheim Altarpiece has had on the German painter’s work and on the work of modern and contemporary artists. She has, in particular, organized the following exhibitions: La peinture en mouvement—Les œuvres du musée Unterlinden sous le regard de Robert Cahen (2013), Décor—Adel Abdessemed (2012), Karl-Jean Longuet et Simone Boisecq—De la sculpture à la cité rêvée (2012), and Sous les Tilleuls les modernes, de Monet à Soulages (2011). For the opening of the new wing of the Unterlinden Museum, she is preparing an exhibition entitled 1914-2014—Un siècle de Visages.