Home>Innovative teaching : the winning bet of teaching history through comics

19.10.2017

Innovative teaching : the winning bet of teaching history through comics

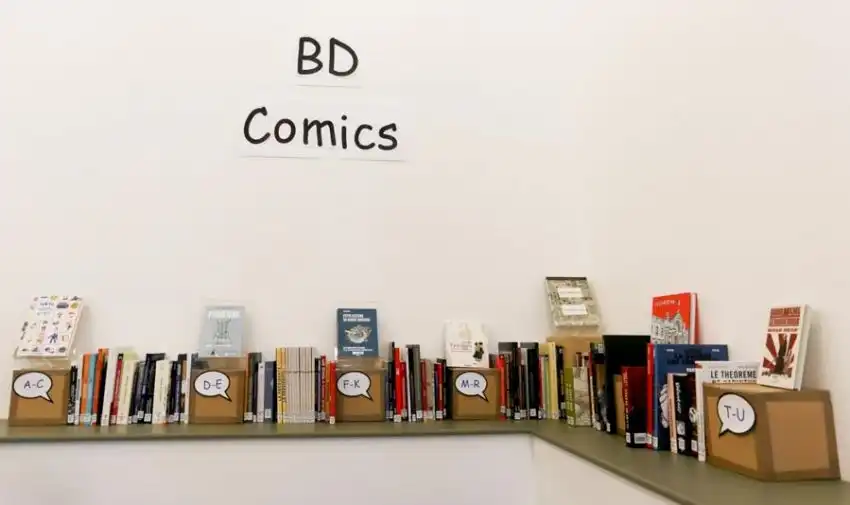

Comics seem particularly suitable for teaching history in an innovative form. The following experiment is being conducted for several years in the Lycée Montaigne in Bordeaux. This job takes approximately twenty hours in a dedicated time, and requires several series of comics; a book is shared, to the most, by two students. An approach using a full comic book, instead of a few panels, allows a broader discovery of the medium. This experiment has been conducted in a different form, during lessons on the Middle East, at the Cairo Institute for Law and International Affairs for the Paris-I University.

Contrary to a common misconception, the younger generation usually has a poor knowledge of comics. I therefore begin by presenting a large number of comic albums, mainly “favorites”, and describing their specifics. My aim is to make the students understand the complexity of comic strips: how it can account for the evolution of the world. I personally prefer focusing my demonstration on contemporary history. I mix the generations of authors, the formats and the genres. For instance, a voluminous and atypical narrative by Emmanuel Guibert, The Photographer; this album, which is splendid, recounts in drawings and photographs a mission with Doctors Without Borders in 1986, during the war in Afghanistan (1979-1989); or small volumes, in the Italian format, with a satirical and unusual tone: A Short History of French Colonies, by Grégory Jarry. I distinguish the four categories which are generally accepted in the world of comics: Asian series, traditional comic strips, also known as Franco-Belgian comics, comics and graphic novels. This gives me the opportunity to explain that comics have become a field of research in history. The thesis in contemporary history I have written in Sciences Po under the tuition of Laurence Bertrand Dorléac, covers the historical graphic memoir. This new genre gathers both written and iconographic productions, based on the personal memory of an author or one of his relatives, which recount a major historical event. The historical graphic memoir differs from a historical fiction, which, although developed from established historical facts, recounts a fictional story.

Once the presentation is complete, I hold a vote among the students; they have to choose the album they are most interested in. This way, they become active in the discovery of the medium and of the historical facts mentioned. Comics can be approached from two different angles. I can read the album in extenso aloud; this method, which is perhaps surprising, has a number of advantages. First, it gives a voice to the text, and a rhythm to its reading, provided that it is done properly. The students are more committed in exploring the drawings; they discover details they may not have seen otherwise. I stop on some panels, I share interrogations with them, I answer their questions. This approach is rarely disagreed. Reading Maus by Art Spiegelman takes several hours and it captivates the readers. The album is the zoomorphic representation of the story of the author’s parents, who are Jews facing the Shoah, represented by mice, the Nazis being cats. This book, which is the only comics album that won the Pulitzer Prize, revolutioned the representation of the genocide of the Jews.

Albums can also be read outside the classes. The students then have a preliminary research work to do on the author(s) and on the album. When in class, each student presents a page which is representative of the album, describes it and explains it. Points of view are then compared. Sometimes, an artistic practice workshop is organized with an author, of whom one of the books was beforehand studied. This allows to better understand the artistic creation process, and possibly to produce a work based on the author’s instructions.

Innovation is both in the method and in the use of the comics’ double language. To the power of words, that of images is added. And these, generally speaking, are more widely understood than words. As Denis Peschanski and Boris Cyrulnik point out, images potentially carry an exceptional semantic richness. The psychiatrist proposes the expression of a “semantized image” to refer to an image having a very strong emotional impact, like a number of those produced in photography and in comics.

Using this medium to teach history allows for a better learning of the facts. When diversely solicited by words and images, the brain recalls more facts. For instance, before reading Medz Yeghern, le grand mal, by Paolo Cossi, few students know the Armenian genocide existed. After the discovery of the narrative, approached in a crude and sensitive manner by the author, all say they will not ignore the event anymore. They are able to quantify human losses, to locate the facts, to explain the extermination process of the Armenian people.

Comics allow for identification to characters that embody the history. History is not a mere accumulation of facts and figures. It becomes real and human; it is embodied in a meaningful narrative. Approaching the book within the class allows for a discussion, a deepening of historical facts, and new interactions. Even the positioning inside the room has changed. I am not standing in front of the students, we are gathered in circle and I am sitting among them. Speech circulates freely, images as well, the history becomes meaningful.

Isabelle DELORME, Agrégée, Doctor of History and Visiting Scholar at the BnF.