We know of Philip Nord’s impressive work on twentieth-century France, but less well do we know of his interest in art. Here, he takes two examples drawn from different eras–late nineteenth-century Impressionism and the post-1945 decentralization of French theater—in order to clarify the terms and conditions for “democratic art.” Such art, which broke with all that preceded it, was in turn to be overtaken by new, more elitist and revolutionary conceptions.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Two Examples of Democratic Art in Pratice:

Impressionism and La décentratlisation théâtrale

Philip Nord

I would like to speak about two artistic movements that called themselves democratic or were seen as such by contemporaries: the Impressionist movement and the movement to decentralize theater in France after the Second World War. My objective is to clarify, on the basis of these two cases, the meaning of democratic art. The two movements crystallized, in part, through their opposition to already well established artistic institutions and aesthetic practices—academic art and boulevard theater—which were criticized as being inaccessible, elitist, or even reactionary. But these democratizing movements were themselves challenged in turn by post-Impressionists and soixante-huitards, for whom the innovations of their elders were not bold enough either from an aesthetic or political point of view. My goal is to demonstrate, first of all, that the idea of democratic art has multiple dimensions, aesthetic, of course, but also institutional and political; and, secondly, that democratic art is a precarious achievement, wedged insecurely between other more elitist or more revolutionary conceptions of art’s role in society.

I will start then with the Impressionists. It is possible to exaggerate the conflict between the painters involved and the Academy of Fine Arts, but the tensions were real. The annual Salon, the premier venue for the exhibition of painting in mid-nineteenth-century France, was controlled by the Academy and the State. Juries determined which pictures were selected and how they were hung, but how did juries themselves get chosen? In 1867, one third of the members were appointed by the State, one third by the Academy, and one third by artists who had received medals at previous salons (médaillés). There was an expansion of the franchise in 1868-1870, coincident with the advent of the Liberal Empire, but new restrictions on the vote were imposed in the wake of the Paris Commune. In 1872, the jury was composed of a mix of state appointees and candidates elected by former médaillés. Universal suffrage was to be avoided at all costs.

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872, oil on canvas , 48x63cm, Marmottan Museum.

Impressionist painters made an effort to penetrate this world but with limited success. In 1866, that year’s Salon jury accepted canvases by Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, but in 1867 the rejection was total. Frédéric Bazille was so infuriated that he pledged never to submit himself again to the “caprice administratif” of an official jury and discussed with Monet the formation of a young artists’ association that would sponsor an exhibition of its own outside of Salon auspices. In 1872, the jury was more stringent still, rejecting three out of every five canvases submitted. There was talk once more among the soon-to-be Impressionists about breaking away from the Salon system. Ludovic Piette, a painter and friend to Pissarro, did not need much persuading. He wrote to Pissarro: “If Courbet is excluded and if the jury is still made of reactionaries and crypto-Bonapartists, I’d join [the venture] and with pleasure”.[ref]Letters from Bazille to his mother (April 1867) and to his parents (May 1867), in Didier Vatuone, Frédéric Bazille, Correspondance (Montpellier: Les Presses du Languedoc, 1992), pp. 137, 140; Piette cited in Jane Mayo Roos, Early Impressionism and the French State, 1866-1874 (Cambridge, England and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 271n33. [/ref]

From early on, there had been a searching about for exhibition alternatives: Manet mounted a solo show in 1867 in connection with that year’s world’s fair. In the 1870s, various dealers sponsored one-man shows of this or that Impressionist. Of greater moment, of course, were the independent exhibitions the Impressionists themselves mounted, eight in all, between 1874 and 1886.

Critic friends of the painters—Philippe Burty and Alfred Castagnary who not coincidentally happened to be confirmed republicans—understood the Impressionists’ confrontation with the Salon in political terms, as an epic battle between the forces of reaction and progress. On the one side stood Adolphe Thiers, chief of the executive power, who “took the part of the ruling classes in art as in politics.”[ref]Castagnary, “Salon de 1872,” Le Siècle, 10 May 1873.[/ref] Thiers had chosen an appropriate second-in-command in the person of Charles Blanc (his Minister of Fine Arts), an old rulemonger who, “like Louis XIV,” “made a cult of the State.”[ref]Castagnary, “Salon de 1872,” Salons, vol. 2 (Paris, 1892), p. 4.[/ref] Together, they had imposed an “entirely authoritarian” regime on the Salon, reducing the right to vote to “a privileged few.”[ref]Burty, “Le Salon de 1873,” La République française, 15 May 1873; idem., “Le Salon de 1874,” La République française, 20 June 1874.[/ref] From the standpoint of republican critics, the sooner the corpse of academic art was shuffled off the better. For, a new kind of painting stood at the ready, the fruit of a rising generation in tune with the “aspirations of modern society.” This was an art based on observation that had rid itself of the disguises and phantasmagorias of old. Its subject was France, its peasants, and its landscapes. Farewell to the satyrs and Cleopatras, which were good only for the Salon; the new painting had replaced them with men and women engaged in the daily pursuits and pleasures of modern life. In a campaign speech delivered in Grenoble in 1872, Léon Gambetta had announced the sudden irruption into public life of a new category of voter, “a new social stratum,” as he called it. Castagnary proclaimed not a year later that “the new social strata” had broken into the world of art as well, a breakthrough he celebrated as “a great sign of democratic progress.”[ref]Castagnary, Salons, vol. 2 (Paris, 1892), pp. 60-61. See also Camille Pelletan’s reviews of the Salon of 1872 in Le Rappel, 18, 20, and 27 May 1872.[/ref] It is not hard to decipher the ideological thrust of such a discourse. Impressionist painting—laîque (secular), modern, French, democratic—was républicain, while academic painting was its opposite.

The story, however, does not end here. In the 1880s and 1890s, the Impressionist painters began to enjoy a measure of success and official recognition from a new-founded Republic, and they would be contested in their turn. The challenge came from two sides: first, from divisionnistes like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac; and then, from Paul Gauguin, Emile Bernard, and company, who were on the look-out for a more spiritual art. The contestation was both aesthetic and political.

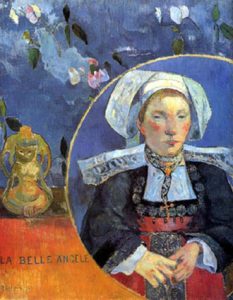

Paul Gauguin, La Belle Angèle, 1889, oil on canvas, 92x73cm, D’Orsay Museum, Paris.

On the aesthetic front, Seurat and Signac did not set out to capture fleeting sensations but instead to distill experience. The neo-Impressionists, as they came to be known, broke down the visual into myriad points, accumulating and juxtaposing dabs of paint to reconstitute what was seen, paring away the transient in pursuit of the permanent forms and elemental harmonies that underlay the surface of things. Gauguin detested such a scientistic approach, dismissing Seurat and Signac as so many “little chemists,” and he parted ways as well with his erstwhile Impressionist friends. What counted, Gauguin wrote to a friend in 1888, was not a slavish faithfulness to things seen:

Don’t paint too much from nature. Art is an abstraction which, dreaming before nature, you take out of it. Think more of the creation that will result; the only way to climb toward God is to do as your Divine Master does: create.[ref]Letter from Gauguin to Emile Schuffenecker, 14 August 1888, in Maurice Malingue, Lettres de Gauguin à sa femme et à ses amis (Paris: B. Grasset, 1946), p. 134 ; see also Malingue, La Vie prodigieuse de Paul Gauguin (Paris: Editions Buchet/Chastel, 1987), p. 78.[/ref]

With the setting of new aesthetic agendas, a political distancing occurred at the same time. Signac and his confrerestook an interest in anarchism. As for Gauguin and the circle of friends he developed in Pont-Aven, Pissarro dismissed them as: “catholico-primitive symbolos,” political reactionaries who were working hand-in-hand with the bourgeoisie.[ref]Letter from Pissarro to his son Lucien, 8 October 1896, in Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, vol. 4 (Paris: Editions du Valhermeil, 1989), p. 271.[/ref] Art historians speak of a crisis of Impressionism. That crisis was generational and aesthetic, but it was also political: a democratic art coming under fire from artistic currents discontented with its easy ways and political good conscience.

That same trajectory—from democratic contestation to the contestation of democratic good conscience—was traced in the theater world after the Second World War. There emerged in the postwar era a self-styled democratic theater. Here, I refer to the five Centres dramatiques nationaux (CDN), the first of them dating from 1947, the CDN de l’Est under André Clavé. It was followed by the Comédie de Saint-Etienne under Jean Dasté; the Grenier de Toulouse co-directed by Charles Dullin; the CDN de l’Ouest under Hubert Gignoux; and last of all the CDN de Provence, founded in 1952, under the direction of Gaston Baty. To these may be added the Théâtre national populaire (TNP), which was run by Jean Vilar from 1951.

The new, postwar theater understood its “democratic” character in relational terms. It was democratic in contrast to the old boulevard theater which was decried as a theater for the bourgeoisie. The target was in many ways a natural one. In its interwar heyday, the typical boulevard play titillated with tales of sex and adultery but never went so far as to subvert conventional morality. Set design, direction, and the actor’s skill, all took a back seat to sparkling dialogue that emphasized wordplay over emotional depth.

A challenge to the boulevard formula had already begun to crystallize during the interwar decades, led by four theater directors known as the Cartel: Baty, Dullin, Louis Jouvet, and Georges Pitoëff. These directors were not so much interested in mondanités as in creating a sense of enchantment and communion, and to that end they experimented with a repertoire of innovative techniques. As Baty saw it, France’s penchant for Cartesian individualism had fed a joyless intellectualizing, which in drama found expression in the cult of the star and in the idolatry of the written word: “Sire, le mot,” as he called it.[ref]Baty, Le Masque et l’encensoir (Paris: Librairie Bloud et Gay, 1926), p. 296.[/ref] As an antidote to star-centered theater, the Cartel directors insisted on ensemble acting. As an antidote to a theater of words, they favored a more physical style of performance, at the same time simplifying set design and experimenting with lighting effects in order to restore a touch of magic to a theater grown too worldly.

In the forties, the Cartelist challenge would be carried forward, but with additional refinements. Under Vichy, a younger generation of Cartel-inspired theater directors, with support from the arts organization Jeune France, looked for ways to make the new theater more accessible. Innovative technique remained at the heart of the project but was now married to a repertoire that would be appealing to the demos, drawn above all from the classics of the French stage: Corneille, Racine, Molière. Accessibility also meant bringing the theater to the people in a quite literal sense. Jeune France supported itinerant troupes, like Dasté’s La Saison nouvelle (Vilar also worked there) and Clavé’s La Roulotte. It funded as well Pierre Barbier and Pierre Schaeffer’s Portique pour une jeune fille de France, a pageant about the life of Jeanne d’Arc, staged in 1941 in a series of remarkable, open-air sites, a public square in Toulouse, a velodrome in Marseille. The idea was to use setting and venue to make theater a genuinely popular medium.

The Liberation-era theater built on these precedents, imparting to them a more democratic gloss. Under Vichy, theater reformers had excoriated the Third Republic, which was accused of corrupting the public, and cast themselves as the regenerators of a popular taste grown decadent. At the Liberation, the discourse focused on reconstruction: France needed to be rebuilt, to be modernized and purified. It was the State’s duty to serve the people, and in this context, theater was reconceived as being itself a public service, “just like gas, water, and electricity,” in Vilar’s still famous phrase.[ref]Vilar, Le Théâtre, service public et autres textes (Paris: Gallimard, 1986), p. 173.[/ref]

Jean Vilar at the time of the Théâtre national populaire (TNP).

But what did it mean for theater to function as a service public? It meant above all bringing quality theater to as wide a public as possible, and quality meant, much as it had in the interwar decades, the canon of time-tested greats. More than half the dramas staged by the TNP in its early years were classics, but these were, it should be stressed, classics made new. The physicality of the acting, the ensemble casts, and the austerity of the staging all made for an experience of exceptional collective intensity. Vilar got rid of the front-stage curtain, constructing instead a proscenium that jutted into the theater. The drama now played out in the audience’s very midst, taking on “the aspect of a ceremony,” as Dasté recollected it.[ref]Jean Dasté, Voyage d’un comédien (Paris: Stock, 1977), p. 120.[/ref]

It was expected that the theatrical canon, its original magic restored through reinterpretation, would draw in the crowds, but in case the public was slow to respond, theater reformers concocted ways to boost turn-out. Vilar’s TNP held space for a whopping 2,600, and to attract audiences in such numbers, tickets were sold at a fraction of the cost of private theater seats; there were special rates for group subscriptions; and the show got started at an earlier hour than on the boulevards to make it easier for an after-work crowd to attend.

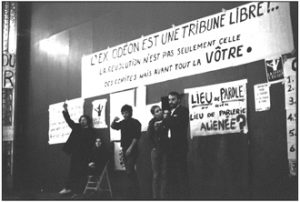

Publics discussions at the Odéon Theater, Paris, May 16, 1968.

Yet, this vision of a theater, at once modern and democratic, was not without its critics. Already in the 1950s, the young, Marxist-leaning critic, Roland Barthes, advocated a Brechtian revolution that would take a more critical, indeed, contestatory view of culture and politics. Come 1968, and the attack on the postwar new deal in theater became that much more acute. From the soixante-huitard perspective, postwar théâtre populaire was lacking in three critical respects. It was too focused on the classics and not enough on creation. It was still too wedded to traditional practices, to theatrical devices aimed at creating enchantment. A genuinely radical theater would expose the machinery of illusion and reveal to audiences how theatrical effects worked. Better still would it be to jettison all the tricks of traditional theater in favor of spontaneity in the manner of The Living Theater or to take drama outside altogether and into the streets, staging happenings or so-called guerrilla theater. Third and not least of all, la décentralisation théâtrale was denounced as beholden to the Gaullist State. It was a subsidized theater, and Vilar himself was apostrophized as “Béjart, Vilar, Salazar.”

In 1968, Barthes’s Marxist critique was taken a step further in the name of a leftist vision of what genuine popular theater should be. And so, the pattern repeated itself. Academic art and boulevard theater were castigated in the name of democracy, but once a new democratic order was ensconced and its routines established, it too was subjected to criticism for insufficient experimentalism and a failure of political will.

What then is one to conclude? When talking about democratic art, aesthetics alone are not the issue; institutional forms are involved as well. And while democratic art may have its moments forts, it is never secure, hemmed in as it is between movements against which it defines itself and contestatory movements which its very success invites into being.

Bibliography

GOETSCHEL, Pascale. Renouveau et décentralisation du théâtre (1945-1981), Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 2004.

LOYER, Emmanuelle. Le théâtre citoyen de Jean Vilar: Une utopie d’après-guerre. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1997.

NORD, Philip. Les Impressionnistes et la politique. Paris: Tallandier, 2009.

NORD, Philip. France’s New Deal: From the Thirties to the Postwar Era. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

ROOS, Jane Mayo. Early Impressionism and the French State (1866-1874). *Cambridge, England and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Philip Nord is a professor of European History at Princeton University, where he has taught since 1981. He is the author of numerous works on the history of France, including: Paris Shopkeepers and the Politics of Resentment (Princeton University Press, 1986); The Republican Moment: Struggles for Democracy in Nineteenth-Century France (Harvard University Press, 1995); Impressionists and Politics: Art and Democracy in the Nineteenth Century (Routledge, 2000); France’s New Deal: From the Thirties to the Postwar Era (Princeton University Press, 2010). He will become the Director of the Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Research at Princeton, in 2012.