We are familiar with the foundational book written by Maureen Murphy, L’imaginaire au musée. Les arts d’Afrique entre Paris et New York de 1931 à 2005 (Les Presses du Réel, 2009). Here, Murphy reexamines how non-Western works of art have been treated, from the moment when they were placed on the bottom rung of the evolutionary ladder until today. Their status changed along the way, thanks in part to the gaze of modern artists, who saw in them beautiful objects in their own right capable of stimulating these artists’ own world of forms. But the process of their “recognition” is not shielded from the dangers of “cooptation” or from the old reflexes, as if a cheap and trashy exoticism continued to enchant the history of art.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Masterpieces are born free and equal

Maureen Murphy

“So that masterpieces from the world over might be born free and equal.” Such was the title of the petition favoring the entry of extra-Western arts into the Louvre Museum. This petition was published in 1990 by Jacques Kerchache in the Parisian newspaper Libération. Long placed at the bottom rung of the evolutionary ladder, extra-Western products were considered as cultural and artistic products only at the start of the last century, the outlook of avant-garde artists having largely contributed to this ascension. He who says highlighting [mise en valeur] is not, however, necessarily saying equal treatment. Between recognition and cooptation, the boundary is thin. In considering two key cultural events (the 1966 Festival mondial des arts nègres [World Festival of Black Arts] and the 1989 show Magiciens de la terre [Magicians of the Earth]), the present talk will question the part art plays in power relations between Africa and the West.

1. Post-Independence: The Festival mondial des arts nègres (1966)

Associated with modernity in art both before and then after World War II in Paris, the arts of Africa were going to follow the transfer of modern art from Paris to New York after World War II and to be given support by such institutions as MoMA and Nelson Rockefeller’s Museum of Primitive Art, which was inaugurated in 1957 and whose collections would constitute the starting point for the “primitive” arts collections at the Metropolitan Museum of New York[ref]Maureen Murphy, De l’imaginaire au musée. Les arts d’Afrique entre Paris et New York (1931-2005) (Dijon: Les Presses du réel, 2009). [/ref]. In the 1960s, the arts of Africa began to acquire a form of respectability and became associated with luxury and social prestige.[ref]A major event in the history of the reception of the arts of African took place in 1966 with the sale of the Helena Rubinstein collection, whose works of African art were sold at prices never before attained. Rubinstein, known as the “Princess Gourielli,” had founded the eponymous brand of cosmetics. In New York, she embodied French chic, luxury, and elegance as well as the avant-garde in femininity. [/ref]

In 1966, the first President of the Senegalese Republic, Léopold Sédar Senghor, organized the Festival mondial des arts nègres in Dakar and in Paris to celebrate the newly independent countries of Africa and to emphasize Africa’s participation in the “Civilization of the Universal.” The photograph we shall study here was taken as part of an illustrated report published in the magazine Paris Match apropos of this Festival, which had taken place at the same time as the Cannes Festival. This set of circumstances undoubtedly explains the attention journalists paid to fashion (the issue was filled with photographs of such stars as Jeanne Moreau and Brigitte Bardot) and the fact that the entire issue was treating, with a tone of frivolity, exoticism, and faddishness, a nevertheless major cultural and political event.

Extrait de “L’art nègre,” Paris Match, 21 mai 1966

The photo, executed by Tony Saulnier, the collector who had organized the meal, was captioned as follows: “In Paris, on Rue Jacob, a dinner of head collectors.” The feeling of discomfort induced by this strange and carefully prepared staging undoubtedly results from the contrast between the affected dress of the guests and the masks they were wearing—between, on the one hand, the world of luxury, embodied in the lavish decor of this bourgeois apartment, and, on the other, the masks that take us back to a certain idea of primitive, tribal, mysterious Africa. The whole setup verges on the grotesque, the unnatural.

The feeling of strangeness aroused by the linking of contrasting symbols was reinforced by the captions that accompanied the image. A “dinner of collectors of heads” and not a “dinner of collectors of objects” or of “masks,” but really of “heads.” The term refers back to the idea of the warrior trophy, to the shrunken heads of South America preserved as war trophies, or to the Maori heads of New Zealand. In reading the title quickly, one also associated “dinner” with “heads,” which confers upon the scene an anthropophagous dimension. In the caption, the author mentions a “plate of caviar” as well as the fact that a mask similar to the one in the foreground “is said to have been purchased for eight million [francs] by a museum.” The guests thus honor the masks from Africa by associating them with the realm of luxury, but at the same time they also send back their exotic charge, through the clearly staged contrast.

A few pages further on, the niece of President Senghor is photographed in front of a set of Ashanti weights, showing off a necklace as she would have done for some fashion magazine. She poses as if she were exhibiting jewelry, while these are in fact weights produced by the Ashanti Kingdom that were used for economic transactions. On another page, one sees photographs of a series of royal thrones from the grasslands of Cameroon; these sacred thrones made in effigies are arranged on a beach for who knows what reason, with, in the distance, the silhouette of a woman stretched out, reminding one of the pinup figures of the time.

In 1966, the fashion reference was devoid of political or ideological meaning at a moment that was nonetheless historic. And one can also interpret the flippancy of the reportage as a means of minimizing the historical import of the event—or at least of erasing its political aspect in order to relegate it to the rank of pure entertainment.

2. What is Implicit in the “Dinner of Head Collectors”, by Bernard Rancillac

That same year, a French artist, Bernard Rancillac, seized upon this subject in order to reveal its neocolonial subtext. Faithful to his “critical figurative” approach, the artist drew inspiration from this issue of Paris Match in order to execute a dual work operating on the model of advent calendars, where one uncovers hidden figures by lifting the flaps. In this way, the figure of Franz Fanon appeared on the right-hand side, Malcolm X on the left, and Patrice Lumumba in the lower portion.

These were vivid figures from the anticolonial struggle, Fanon in Algeria, Malcolm X in the United States, and Lumumba in the Congo. The painting, as often in Rancillac’s work, took back up this Paris Match page while reversing the color tonalities, red and yellow predominating overall, which gave the impression of an inferno, as if the work were going to catch fire or was already in the processing of flaring up, like the decolonization movements that were then stirring up the colonized countries.

And yet, the decolonization movement was already well underway, if not yet completed, by 1966. Moreover, Rancillac chose three figures that, by that year, were all deceased: Fanon died in1961, Lumumba was arrested and assassinated in 1961, and Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965 in the United States. Undoubtedly, Rancillac wanted to put his finger on the relativity, the fragility of decolonization movements.

Though independent in the 1960s, African countries ultimately had little margin of maneuver to develop beyond the tutelage of Europe.[ref]Citons par exemple les propos de Robert Goldwater, alors directeur du Museum of Primitive Art n’écrivait-il pas à Nelson Rockefeller, hésitant à prêter des objets au Festival: « Monsieur Chatelain, directeur des musées de France et Administrateur de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux m’a assuré, à la réunion de l’ICOM, qu’il n’y avait aucun danger de changement de Gouvernement au Sénégal (sous ferme supervision française) ou d’expropriation extérieure. Le commissaire national du Sénégal ainsi que le Président Senghor m’ont tous deux assuré en privé et par écrit, publiquement, qu’aucune revendication d’aucune sorte ne serait tolérée par leur Gouvernement. Nous sommes très excités à l’idée de prendre part au symposium de Dakar. Lettre de Robert Goldwater à Nelson A. Rockefeller du 9 février 1966, fichier 1675, boîte 163, séries « Projects », groupe de classement 4, collection Nelson A. Rockefeller, archives du Rockefeller Archive Center, Croton Fall, New York.[/ref] What occurs in this work is a real confrontation between art and politics that breaks the frivolity of the reporting so as to allow the bitter figure of aborted struggle to hang over this picture. This reportage, in the end, was relaying some of the mythologies running through French society at the time and spoke volumes about the supposedly equal relations between former colonies and home countries in the post-Independence period.

3. Magiciens de la Terre in the Wake of Celebrations of the Bicentennial of the French Revolution

To conclude, I would like to investigate another major cultural event—the 1989 Magiciens de la terre exhibition—that marks the entrance of extra-Western contemporary art onto the stage of the international art market and raises the question of equality in the contemporary world. If the Festival mondial des arts nègres was the occasion for Senghor to launch what was called the “Dakar” school of art,[ref]See, on this subject, Elisabeth Harney, In Senghor’s Shadow: Arts, Politics, and Avant-Garde in Senegal, 1960-1995(Durham: Duke University Press, 2004). [/ref] a set of artists educated at the Dakar School of Fine Arts with a rather academic mindset close to Senghor’s theories of négritude, how was contemporary artistic creativity perceived, approximately twenty years later, in the West?

In 1989, it was not the artists of the Dakar School who were retained for the Magiciens de la terre exhibition, which, I recall for the reader, was an exhibition devoted to a confrontation between contemporary Western art and extra-Western contemporary creative work on an equal footing, the project fitting into the programming of events tied to the commemoration of the French Revolution. It was a matter of introducing the present moment of creative work taking place in the world without limiting oneself to Europe and the United States. This desire for openness was commendable in its own right, but the method adopted poses questions and gave rise to lively debates.[ref]See, for example, Thomas McEvilley, “Opening the Trap: The Postmodern Exhibition,” in Art & Otherness: Crisis in Cultural Identity (Kingston, NY: Documentext/McPherson, 1992). [/ref]

In relation to the diversity of creative work taking place during that period, who were the artists whose work was accepted? For Senegal, the curators chose to exhibit Seyni Awa Camara, a self-educated craft artist who sold her sculptures in the markets of Casamance. The “Dakar School” was undoubtedly deemed too academic and was not retained for the show.

Yet there also existed a dissident arts scene, critical of the Dakar School, involved in performance and actionism and dominated by Issa Samb. This artistic current was not retained, either, for it was no doubt insufficiently “African” or authentic, too close to Western forms of artistic creativity.

To represent South Africa, the curators took the work of Esther Mahlangu, an artist from the Ndebele cultural group, a group that has, since the 1940s, embodied an Edenic, primitive, and authentic view of Africa. One aspect of the social and economic life of this group not often spoken of resides, however, in the fact that it concerns a minority whose cultural identity was consolidated by its exclusion and its confinement on reservations.

In 1971, eight separate African States were created in South Africa. Like many millions of Black Africans, the Ndebeles were dispossessed of their lands, which were supposed to be returned to Whites, and scattered over the entire territory in “homeland” reservations, or “Bantustans.” These reservations were situated north of the city of Pretoria and a new State was allocated to them, the “KwaNdebele” State. They lost their South African civil rights and therefore became foreigners on their own lands, migrants who commuted every day to work in Pretoria.

David Goldblatt photographed the movements of the Ndebeles in 1983-1984, daily round trips that can last up to nearly eight hours. Golblatt’s project was not accepted for Magiciens de la terre, and it was the work of Esther Mahlangu, a “traditional” Ndebele painter, that was exhibited. Why not have shown Goldblatt’s photography or the paintings of a South African artist such as Ernest Mancoba,[ref]See, concerning Mancoba, Elza Miles’s Lifeline Out of Africa: The Art of Ernest Mancoba (Cape Town: Human & Rousseau, 1994) and Sarah Lignier’s Ernest Mancoba 1904-2002. Regards croisés entre l’Afrique et l’Occident au 20ème siècle, a graduate research thesis directed by Jean-Hubert Martin at the École du Louvre (Paris, June 2008).[/ref] whose works were acquired by the French State in 1979 and 1989?

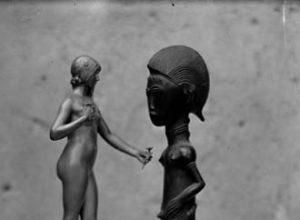

Ernest Mancoba, Dessin sans titre, encre et pastel sur papier, 50 x 32,5 cm, 1976.

Mancoba’s academic and artistic career path developed by way of the missionary schools of South Africa. In 1938, he obtained a scholarship grant to pursue his teacher education in France. He enrolled in the École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, where he met his future wife, Sonja Ferlov, whom he married in the Saint Denis internment camp in 1942. Ferlov was a student of Alberto Giacometti and had her studio alongside his in Montparnasse. It was through her that Mancoba met Giacometti, with whom he became friends. In 1947, the couple moved to Denmark, where he participated in the artistic activities of the CoBrA group.

Mancoba’s work is closer to French abstraction than CoBra and exhibits a connection with the international arts networks of the time. This openness undoubtedly explains why his work was not accepted for the Magiciens de la terreexhibition, for it was undoubtedly considered insufficiently “African” and too close to international artistic currents.

One could have thought at the time that Magiciens de la terre opened the way to Post-Modernism—that is to say, to a reorientation of people’s ways of seeing, to an openness onto the world and to the establishment of a fairer, more egalitarian relationship between North and South, former colonies and former home countries. This show could have established a break with the modernist, universalist approach that sought to find resemblances with what is the “same,” to universalize form.[ref]Apropos of the discussions instigated, for example, by the Primitivism in 20th Century Art exhibition organized by MoMA in 1984, see Yve-Alain Bois, “La Pensée Sauvage,” in Art in America, April 1985: 178-89, and James Clifford, “Histories of the Tribal and the Modern,” in ibid.: 164-74.[/ref] And yet, through the very nature of its choices, the exhibition reactivated the “nègre-primitive” pair in a nostalgia for primitivism that still today marks one’s perception of the arts of Africa.

The history of contemporary art in Africa and of its reception in the West remains to be written. In order to exit from the impasse in which discussions about “contemporary African art” and the legacy of colonialism seem to be stuck, it is time to take these questions seriously, studying them in a scholarly and historical manner. It is time, too, to get out from under the implicit moralizing yoke found in postcolonial studies, so as to envisage extra-Western creativity on an equal footing, yet without forgetting the real, existing economic disparities.

Selected Bibliography

BOIS, Yves-Alain. “La Pensée Sauvage.” In Art in America, April 1985: 178-89.

CLIFFORD, James. “Histories of the Tribal and the Modern”, in Art in America, April 1985: 164 -174.

HARNEY, Elisabeth. In Senghor’s Shadow: Arts, Politics, and Avant-Garde in Senegal, 1960 – 1995. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

McEVILLEY, Thomas. Art & Otherness: Crisis in Cultural Identity. Kingston, NY: Documentext/McPherson, 1992. French trans. Yves Michaud. L’identité culturelle en crise, Art et différences à l’époque postmoderne et postcoloniale. Nîmes: Jacqueline Chambon, 1999.

MILES, Elza. Lifeline Out of Africa: The Art of Ernest Mancoba. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau, 1994.

LIGNIER, Sarah. Ernest Mancoba 1904-2002. Regards croisés entre l’Afrique et l’Occident au 20ème siècle. Graduate research thesis directed by Jean-Hubert Martin at the École du Louvre. Paris, June 2008.

MURPHY, Murphy. De l’imaginaire au musée. Les arts d’Afrique entre Paris et New York (1931-2005). Dijon: Les Presses du réel, 2009.

Maureen Murphy, an art historian, is a Lecturer at the University of Paris 1-Panthéon Sorbonne. Her research bears on the history of the reception and representation of the arts of Africa in Western museums, the ties between the latter and modern art, contemporary African art, and postcolonial theories. She is, in particular, the author of De l’imaginaire au musée. Les arts d’Afrique à Paris et à New York (1931-2006)(Dijon: Les Presses du réel, 2009).