Home>A right to a human decision

21.11.2024

A right to a human decision

About this event

21 November 2024 from 15:30 until 16:30

Online

Organized by

Sciences Po Law School

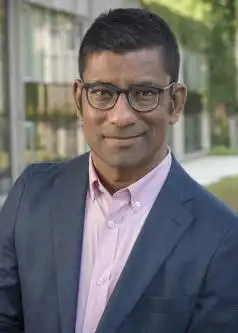

Aziz Z. Huq is Frank and Bernice J. Greenberg Professor of Law at the University of Chicago, School of Law. He is a scholar of US and comparative constitutional law. His recent work concerns democratic backsliding and the regulation of AI. His award-winning scholarship is published in several books and in leading law, social science, and political science journals.

Abstract from Aziz Z. Huq, ‘A Right to a Human Decision’, published in Virginia Law Review, volume 106, issue 3, available here:

Recent advances in computational technologies have spurred anxiety about a shift of power from human to machine decision makers. From welfare and employment to bail and other risk assessments, state actors increasingly lean on machine-learning tools to directly allocate goods and coercion among individuals. Machine-learning tools are perceived to be eclipsing, even extinguishing, human agency in ways that compromise important individual interests. An emerging legal response to such worries is to assert a novel right to a human decision. European law embraced the idea in the General Data Protection Regulation. American law, especially in the criminal justice domain, is moving in the same direction. But no jurisdiction has defined with precision what that right entails, furnished a clear justification for its creation, or defined its appropriate domain.

This Article investigates the legal possibilities and normative appeal of a right to a human decision. I begin by sketching its conditions of technological plausibility. This requires the specification of both a feasible domain of machine decisions and the margins along which machine decisions are distinct from human ones. With this technological accounting in hand, I analyze the normative stakes of a right to a human decision. I consider four potential normative justifications: (a) a concern with population-wide accuracy; (b) a grounding in individual subjects’ interests in participation and reason giving; (c) arguments about the insufficiently reasoned or individuated quality of state action; and (d) objections grounded in negative externalities. None of these yields a general justification for a right to a human decision. Instead of being derived from normative first principles, limits to machine decision making are appropriately found in the technical constraints on predictive instruments. Within that domain, concerns about due process, privacy, and discrimination in machine decisions are typically best addressed through a justiciable “right to a well-calibrated machine decision.

About this event

21 November 2024 from 15:30 until 16:30

Online

Organized by

Sciences Po Law School